'Ante-','Anti-' 'Post-'...modernity: Post-liberalism, ‘Indigenisation’ and Resettling the Commons

Thinking aloud about the crossover between Christian conservatism, green localism, leftist tropes of 'indigeneity' and 'decolonization', and distributism as a vehicle for iconic markets.

In this essay, I kind of kick my football into the gardens of

and others, in the hope that they kick it back.NOTE:

was confused by my use of the pre-fix ‘ante’: “If that isn't what you mean [i.e. ‘Anti’] I must confess that your usage is very confusing.” He’s not wrong. I meant ‘ante’. I was intending to confuse a little because of the way the shades of ‘anti-’, the retrospective ‘ante-’ and ‘post-' tend to run together, particularly in green commentary. is probably ‘anti-modern’, but advocates for a kind of ante-modernism, and is skeptical about the possibility of an alt-modernism. I’m not sure whether my own distributist and increasingly tech-skeptic orientation is anti- or some steam-punk ante/post /alt modern. So I used the pre-fix deliberately to confuse. However, Ryan is probably right. Apologies for confusion. Comments welcome.We don’t know when, where or why we are

A corollary of the ‘meaning crisis’ – the collapse of a deep-seated, precognitive and shared mythology – is that we are completely lost. We don’t know when or where, let alone why, we are.

Politics and sociology are rife with prefixes denoting stages or phases of human development. Modernity is capitalist, liberal and industrial. The past was pre-modern and pre-industrial. The muddy, post-medieval build-up is dubbed Early Modernity. And what comes now and next used to be called socialism – if you were a Marxist believer. For the depressed apostates of the 1980s the epoch de jour was dubbed late-modernity, post-Fordism or, for hard core cynics, postmodernism. Although those in North America, who would, a generation ago, have been Leninists or Maoists, remain bellicose anti-capitalists, their inventory of alternative political economic models is threadbare. Luckily the new argot of identity politics makes few demands for temporal coherence. The identitarians are not concerned with stages, or even to be honest with historical resolutions. The gloriously incoherent project of decolonization simultaneously moves back to indigenous society before the advent of Europeans, and forward to an unspecified after-modern/post-capitalism.

On the other hand, for those ecologists who have given up on even the indigenous Eden, the geological coming of age of ‘Homo deus’ was dubbed the Anthropocene – a appellation that evokes despair, but also a glint-eyed hubris in tech-tycoons hawking mega-projects such as geo-engineering, Martian colonies and those Arcologies of Paolo Soleri, made so familiar by decades of science fiction blockbusters.

For those of a calmer, Eeyorish disposition, modernity has become a radically secular ‘age of authenticity’ and ‘expressive individualism’ (Charles Taylor), narcissism (Christopher Lasch) or chronic mental instability (@jonathanhaidt). And finally, there are those who believe we are witnessing the death of liberalism as the most functional carapace for capitalism[1] and anticipate a new era of postliberalism.

It's all so bloody verbose – and yet necessary. To talk about the overall configuration of society, its antecedents and possible futures, is to invite typological fetishism. So just for the record, I’m with Charles Taylor, Jonathan Haidt, Christopher Lasch, John Senior, Phillip Rieff, Alasdair Macintyre and company, and a postliberal (whatever that turns out to be). Society is changing rapidly. But modernity is precisely a condition in which, as Marx said, ‘all that is solid melts to air’. This essay is really about the extent to which the arc of modernization might be tempered with the re-emergence of social, familial and even market structures that pre-date both capitalism and the nation-state.

I refer to this cluster of possibilities by the Polanyian term Livelihood which stands in tension with the dyadic couplet of Market and State. What is at issue for some greens, for all Christians and for conservative or post-liberal critics of modernity is not a utopian attempt at counter-Revolution. Augustinians may fix their gaze on a possible City of God, but do not expect actually to realize something that is so dependent on God’s grace. Civilisation is not a game of Catan. Utopian construction according to abstract plans invariably ends badly. So rather than reconstruct humanity from the top down, these critics seek to ameliorate, temper and work with the grain of human nature. Rooted in Natural Law, their assumption is that if, guided by appropriate metaphysics and cultural values, networks of individuals prioritize the right individual and societal goods — icons rather than idols — and cultivate classical virtues, many if not most of our social, ecological and economic travails will right themselves. People will be happier, society more resilient and ecosystems less stressed.

In what follows I’m going to explore this idea through the language of settlement and the commons: living in particular places and managing common pool resources. Rejecting the incoherent Marxian conflict theory implicit in trendy aspirations to decolonization and indigenization, I argue for an attenuation of modern economy and society based on Christianity, virtue ethics and a political economy of distributism. It won’t solve all our problems. But it may limit the damage and move us in the right direction. I conclude by suggesting that such a Christian political economy might provide a mechanism for markets to become iconic conduits to broader societal goods as opposed to idolatrous ends in themselves — which is also to say self-limiting and more ecologically sensitive.

Battle of the Oiks

‘Decolonization’ and ‘indigenization’ are the tropes de jour in Canadian and American universities. Taken at face value, they are nonsensical concepts. The hundreds of millions of Europeans, Asians and Africans who have moved to North and South America over the last 500 years are not going anywhere. They are just as much at home as any of the indigenous First Nations who themselves moved over from Asia at various points in the distant past. Those tribes were also hardly less prone to upheaval and strife than their colonial antagonists. They, also, moved around the vastness of continental America displacing each other, often in zero-sum and sometimes genocidal conflict.

By the same token, short of a total collapse, neither the so-called ‘settler culture’ nor the disembedded, once-tribal First Nations can easily escape modernity and (re)-indigenize themselves. The ‘participating consciousness’ and tight knit ‘we identity’ characteristic of pre-modern people, and described wistfully by Owen Barfield and Morris Berman (Barfield, 1988; Berman, 1981, 2000), is at best a penumbral shade at the corner of our mind’s eye. It is unavailable to the highly individualised, detached selves rendered and constructed by the transactional logic of the State and the Market. With the exception of uncontacted groups, such as the Pirahã in the Amazon, indigenous people are fast on the way to being tribal only in name and legal designation — not unlike the good kilt-wearing Scottish denizens of Fergus, Ontario. Barfield compared this loss of participating consciousness and the emergence of the modern self with riding a bike: easy to learn, almost impossible to unlearn. Everyone in the west, and most people in the world, are now riding that bike.

However, that is not the end of the story. There may be different ways of doing modernity. To extend Barfield’s metaphor, albeit clumsily, there may be a choice of bicycles, tricycles and tandems. Modernity without religion – the modernity of Arnold’s ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’ – turns out to be a kind of incipient hell. Its endpoint is transhumanism, and the death of humanity. Since the 1950s, greens have spoken of this in terms of ecological limits to growth. And early on, this translated fairly easily into a species of healthy and reactionary ante-modernism (as with Leopold Kohr’s radical project to break down nation states into something more manageable [Kohr, 1986]). Such thinking was a continuation of the wistful medievalism of 19th century guild socialists such as William Morris or the peasant communalism evoked by Tolstoy. In the zeitgeist of the 1970s, green politics morphed too easily into a familiar kind of philistine anti-capitalism — vengeful, simplistic, hysterical and immune to the reality of trade-offs.

Less well understood is that a certain kind of Burkean conservative was animated by the exactly the same sort of homely concern with ecological integrity. Roger Scruton was an exemplar of this sensibility which circled endlessly around a kind of oikophilia – a love of home, of tradition, of continuity, of the particular and contextual – and an aversion to abstract universalism (Scruton, 2013, 2014, 2018).

Figure 1.

These two orientations to alt/ante-modernity – green and conservative – should have a great deal to say to each other. But the conversation has been stilted, partly because greens have tended to throw in their lot with an anti-capitalist left that is largely modernist in outlook and undiscriminating about the nuances of ‘the market.’ This political stance was in effect an alliance with a social justice variant of liberalism – the most exuberantly modernist philosophy that prioritized a materialist metaphysics of satisfaction-seeking, sovereign individuals and made an idol of equity. And in choreographed symmetry, twentieth century conservatives, in contrast, prioritized their hostility to socialism, and entered an unnatural coalition with the other branch of that same liberalism – the kind of neo-liberalism associated with Margaret Thatcher. Metaphysical materialism, individualism and naturalism was in this case tied to a different idol: ‘the free market’. In short conservative and green oikophiles were separated by their alliance to mutually exclusive variants of liberalism (Figure 1 above). In the 21st century, the national liberalism that has for a century encompassed an uneasy coalition of both of these variants, is dying. This comfortable polarity is falling apart.

Postliberal politics will fracture along the division between oikophiles and oikophobes. This is actually not so new. It’s a new rendering of the Tönnies’ (1963) tension between gemeinschaft (community) and gesellschaft (society) — the couplet that used to be hammered into every first-year sociology student. In place of national liberalism there is a nakedly ILLIBERAL GLOBALISM that is increasingly tied to technocratic government by experts (‘governance’) and allied to sometimes esoteric projects of geoengineering, ecological modernism and transhumanism. For the most part, this project has the support of the major global institutions — World Economic Forum, United Nations, European Union — and at least tacitly, the vast web of mainstream NGOs, from Oxfam to Amnesty International. This is the world of artificial protein synthesis, Net Zero, digital identities, currencies and passports, Chinese-style social control — a Promethean metaphysics of elite-human self-determination orchestrated by political and corporate demi-Gods, a kind of techno-human polytheism.

Instinctively and inchoately, opposition to this project takes many forms including:

1. Most obviously, RIGHTWING POPULISTS – Brexit, Trump, Reform UK, Le Pen’s National Rally, the AfD etc. Here the oikos pertains to nation although much of the political heat comes from the hollowing out and fracturing of much more local communities such as Tommy Robinson’s Luton.

2. A related stream in the emerging milieu is a strain of CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM which focuses the communitarian and relational imperatives of Christian ethics on the imagined community of the nation, on the autonomy of the family and sometimes (somewhat incoherently) on a historical project of renewing Christendom. ‘Christendom in one nation’ is likely, ultimately, to be as successful as ‘socialism in one country’.

3. Less obviously, it includes an unexpected intellectual renewal of CHRISTIANITY in Europe and in the Anglosphere. This includes a burgeoning field of Protestant and Catholic apologetics in the form of popular podcasts and YouTube channels (e.g. Justin Brierley’s ‘Unbelievable’) as well as serious theology (e.g. Barron, 2016; Milbank et al., 1999). The ‘oikos’ here relates to creation as a whole and opposition to the vulgar transhumanist anti-theism of the global liberal project. But it also represents a reaction to the disembedded, self-contained modern self that has emerged on the back of late capitalism (see below). This renewal of the Christian oikos demands not the re-submergence of the individual in some clannish ‘we’. Rather the theology of personhood presses for the individuality of expression and identity to be oriented towards God; and for the tissue of mutual social obligations and familial/community love to function as an iconic doorway for this purpose.

4. Then there are the original ANTE-MODERN GREENS who retain the ‘small is beautiful’ sensibility of their founding fathers – Schumacher, Tolstoy, Gandhi. They are ‘ante’ in the sense of looking to a past cultural integrity overthrown by modernity. Rather a realistic and instrumental anti-modernism, they tend to explore tangential counterfactual and impressionistic trajectories for alternative or parallel modernities. Rejecting the ecomodernism and materialism of the environmental movement, they ask difficult questions of the sustainability movement – not least what exactly is to be sustained. In several high-profile cases – notably the former environmentalist and one-time pagan Paul Kingsnorth, and mythologist and storyteller Martin Shaw – ante-modern greens have become Christians, most often Orthodox or Catholic.

5. Finally, there are also myriad Occupy/Extinction Rebellion type ANTI-CAPITALIST GREENS who advocate forms of localism usually under the aegis of DEGROWTH – the active contraction of the capitalist economy along with (implausibly) the maintenance or even expansion of the state. Along with the architecture of the state, these groups are unconsciously liberal, assuming a continuing pattern of social and spatial mobility, a characteristically modernist ethos of human rights, the valorisation of self-identity and expression and a defiantly Promethean insistence on individual sovereignty albeit expressed through usually unspecified mechanisms for collective action.

Settling and Unsettling

Settlers have a bad rap among progressives in North America. Settlement is synonymous with colonization and modernization. Canadian academic and ‘occupy’ activist Craig Fortier is fairly typical in arguing that decolonization and anticapitalism is best understood as a project of ‘unsettling the commons’ – reversing colonial settlement and recovering indigenous cultures of pooled sovereignty and resource management.

This is ironic because — settler colonialism aside — modernity is really a process of ‘unsettling’ individuals and communities. The most quintessentially capitalist America has been endlessly dynamic precisely to the extent that Americans are perpetually ‘unsettled.’ This is why America has celebrated itself so truthfully and iconically with endless road movies. Always ambivalent about its role in lighting the fuse, England, in contrast, wallows in bucolic denial. The intravenous drip of saccharine evocations of timeless, settled communities and landscapes has been a fixture of Sunday night TV for decades –— Dr Martin, Wind in the Willows, Darling Buds of May, All Creatures Great and Small, Swallows and Amazons, Morse, Midsummer Murders and even Clarkson’s Farm. But even here, the tension is always about the ever-present threat of modernity as with the housing development that triggered the leporine odyssey in Watership Down.

At heart, modern unsettlement involves the proliferation of transactional individualism and short time horizons. The tissue of interdependency, sharing, lifelong, mutual responsibility, that Karl Polanyi refers to as ‘Livelihood,’ characterized subsistence patterns of life – hunter gathering, horticulture, peasant agriculture – for nearly all of human existence. For most people, most of the time, the material and energy flows of everyday life were mediated by shared common pool resources: hunting, grazing, cultivated land, wood for fuel, water courses, aquifers etc. Together, the Market and the State – both mechanisms for aggregating the agency of atomised, billiard ball individuals – and the corresponding projects of left and right, have the partly intended consequence of destroying this pattern of Livelihood. This is the unsettling of the commons.

The localists are Anglo and Christian, even if they don’t always know it

Radicals of all stripes want to reclaim community. It’s a cliché that modernity undermines social capital, generates mental illness or uneasiness (dis-ease) and makes people unhappy and lonely. Radical greens and degrowthers look forward to a societal contraction or collapse because it will somehow save the planet. They talk the language of sharing and localism; but they also tend to assume that this won’t compromise the patterns of individual freedom, mobility, self-expression and lifestyle associated with consumer societies. Even self-designated indigenous activists unironically speak the language of individual human rights and presume a continuing flow of reparatory wergild from the (capitalist, growth-dependent) nation state – all non-negotiable if you have come to depend on planes, trains, automobiles and modern dentistry.

Real sharing is a long-term, ascriptive, covenantal and in some cases, as with marriage, sacramental. It defines who a person is through their relationships, for life. This kind of anthropological sharing is fundamentally incompatible with socialist, capitalist or even libertarian versions of modernity: with any combination of collectivist or market transactionalism. A prerequisite for this kind of localism is that participants cease to construe themselves so much as rational, choice-making individuals — whether responsible citizens, risk-taking entrepreneurs, proud workers, efficient employees, savvy investors or bargain-conscious consumers. This is such a tall order as to be virtually impossible. However laudable the aim may or may not be, we should be sceptical. For two centuries, our uber-mobile society of individuals has been constructing people in terms of an exploding kaleidoscope of autonomous economic and social roles. The pre-cognitive sense of subjective boundedness and autonomy —of sovereignty — is now deeply ingrained into the core of the Western/modern psyche.

Polanyi observed that the tell tale sign of ‘modernity’ is when the ‘economy as such’ becomes a ‘thing’ — a noun in common parlance that people refer to, that can be ‘doing well (or badly)’ and that is straightforwardly and easily distinguished from other domains of life, relating to leisure, or religion, or culture. Charles Taylor makes a corresponding claim about religion. It only becomes an abstract ‘thing’ separable from other aspects of life with the process of secularisation and the privatization of religious experience. Or to use Andrew Willard Jones’ concept, religion and economy both cease to be an aspect of a ‘complete act’—a form of society in which production, consumption, marriage, childcare, leisure, ritual, cosmology, social cooperation are indivisible facets of a single, integrated pattern of life (see my riff on this here).

The kind of localism that both green-localists and Christian-traditionalists hark back to would depend upon just such a ‘complete act’. Thus, any prospect of a livelihood-oriented ‘sharing economy’ would, in fact, not be an ‘economy as such’, at all. The material and energy flows associated with manufacturing, distributing and consuming all the goods and services of daily life would be, to some extent, ‘re-embedded’. The functions of both State and Market would, to a degree, be submerged into an expanded domain of life-long, place-bound and covenantal (rather than contractual) relationships of reciprocation (i.e. Livelihood)

It is possible that we might have a lot to gain from such a process of re-embedding or resettlement. A lower metabolic footprint, smaller flows of energy and materials, might conceivably correlate with better mental health and happiness. A strong and cohesive shared religion might make for more genuinely caring societies and less political conflict (at least within communities. Relationships between communities would be another story). It’s easy to create a fairy story. But in a world with hundreds of more-or-less rival nation states, limited resources and billons of people, it is hard to make a plausible case for a peaceful transition.

The commons

The idea of ‘the commons’ derives via French from Latin ‘communis’ meaning public or shared; but also ‘munia’ which intimates duties or obligations relating to an office or social role or status. But the idea of the commons – referring to ‘a common’, a physical shared piece of land (which is written into the naming of the landscape across England and apparent in pretty well every village and town) – aggregates other meanings relating to ‘estover’ (French ‘estovoir’) meaning ‘that which is necessary’ i.e. the petty resources such as timber and fuel, material for house repairs, for hedges and husbandry etc. that a tenant or member of an estate are allowed to take from the land. This idea emerges well before the Medieval period and is implicit in the Anglo-Saxon idea of ‘bot’ (profit)– as in house-bote, cart or plough-bote, hedge or hay-bote, and fire-bote.’ This endless pattern of mutual imbrication is implicit in legal codes whereby ‘manbot’ was compensation to the lord for when a man under his authority was killed, and wergild was paid to the family. The patchwork landscape of open fields, hedges, covenants, easements, commons, interweaving obligations and shared resources – goes back at least to the 6/7th century and is probably much older, dating back to the pre-Roman Neolithic.

‘the collective organisation of agricultural resources originated many centuries, perhaps millennia, before Germanic migrants reached Britain. In many places, medieval open fields and common rights over pasture preserved long-standing traditions for organising community assets. In central, southern England, a negotiated compromise between early medieval Lords eager to introduce new managerial structures and communities as keen to retain their customary traditions of landscape organisation underpinned the emergence of nucleated settlements and distinctive, highly-regulated open fields’

(Oosthuizen 2013)

So, in fact one can argue that ‘the commons’ both linguistically and in the weave of social and landscape practices, is part of the ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ of Celtic/Romano-Britannic and Anglo-Saxon settlement in England.

Commoning: Less anti-capitalist more ante-modern

And in a similar vein, most contemporary debates about the commons (maintenance, disposition, recovery) are overlaid with the specifically British experience during the early modern period and subsequent processes of capitalist modernization. Thus for example, Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, starts with the Speenhamland laws which he saw as a failed attempt to stabilize the order and social cohesion of the countryside which had been, by the early nineteenth century, been disrupted by centuries of ‘enclosure’ i.e. the dispossession of the peasants’, the denial of the rights of access, easements, and covenants in relation to common pool resources and the emergence of a much simpler pattern of private ownership defined by the unencumbered fungibility of land construed (falsely) as a commodity.

This process of ‘disembedding’ — the simultaneous creation of mobile, ‘free’ wage labourers unmoored from place-bound communities and ancestral landscapes; and fungible, exchangeable commodity-land — was a prerequisite for capitalist capital accumulation. Initially the driver was commercial sheep farming. But the process also caused cascading urban industrialization by creating a steady flow of ‘free wage labourers.’ Freedom was often a mixed blessing. Forced emancipation meant ‘freedom’ to starve, to be insecure and to be dependent on the vagaries of market forces. Commenting on Edmund Burke’s sanguine assessment of the stability and virtue of the traditional rural order, Raymond Williams calculates that over the course of Burke’s life, the House of Commons (irony) passed an act of enclosure every single week for sixty years.

So far so clear, from a ‘social justice’ perspective. Capitalist expropriation dispossessed the poor and created a cycle of exploitation. But of course, the same process created new social classes and ideologies. It led also to the emergence of a new species of psychological individual: selves with a peculiar sense of their hermetic separateness, sovereign agency and potential for self-actualization.[2] Capitalist modernity makes possible or even thinkable for the first time, questions such as ‘Who am I?’ and What might I become?’ All of the framing compass points of modern polities — democracy, liberalism, conservatism, socialism, citizenship, natural rights, human rights — emerged only in the wake of the modernization.

At this point, North American activists such as Craig Fortier take their cue from ‘anti-authoritarian’ (aka anti-capitalist) organizers. As with the long succession of movements contesting the terms of modernization — socialists, anarchists, the Diggers, communards, Owenites, the William Morris Society — the umbrella of initiatives that came under the ‘occupy’ label pushed back against private property. The difference is that the process of modernization has gone so far that, in the case of what they call colonial settler culture, there is no ancestral memory or lived residue of living through, and with, the commons. In fact, in North America the landscape is shorn of all of those historic patinas that are still discernible in European social relations and landscapes e.g. foot paths, protected landscapes, tow paths, foraging rights, commons, heaths, rights to roam and ramble, rights to lay-by. In North America, the abstract grid-iron landscape of 100-acre plots points to social-ecological relations that are highly simplified and capitalized. There is very little to build upon other than a homesteading pioneering tradition that was already highly disembedded, individualistic and impoverished with regard to the density of commoning interdependencies.

Commons density

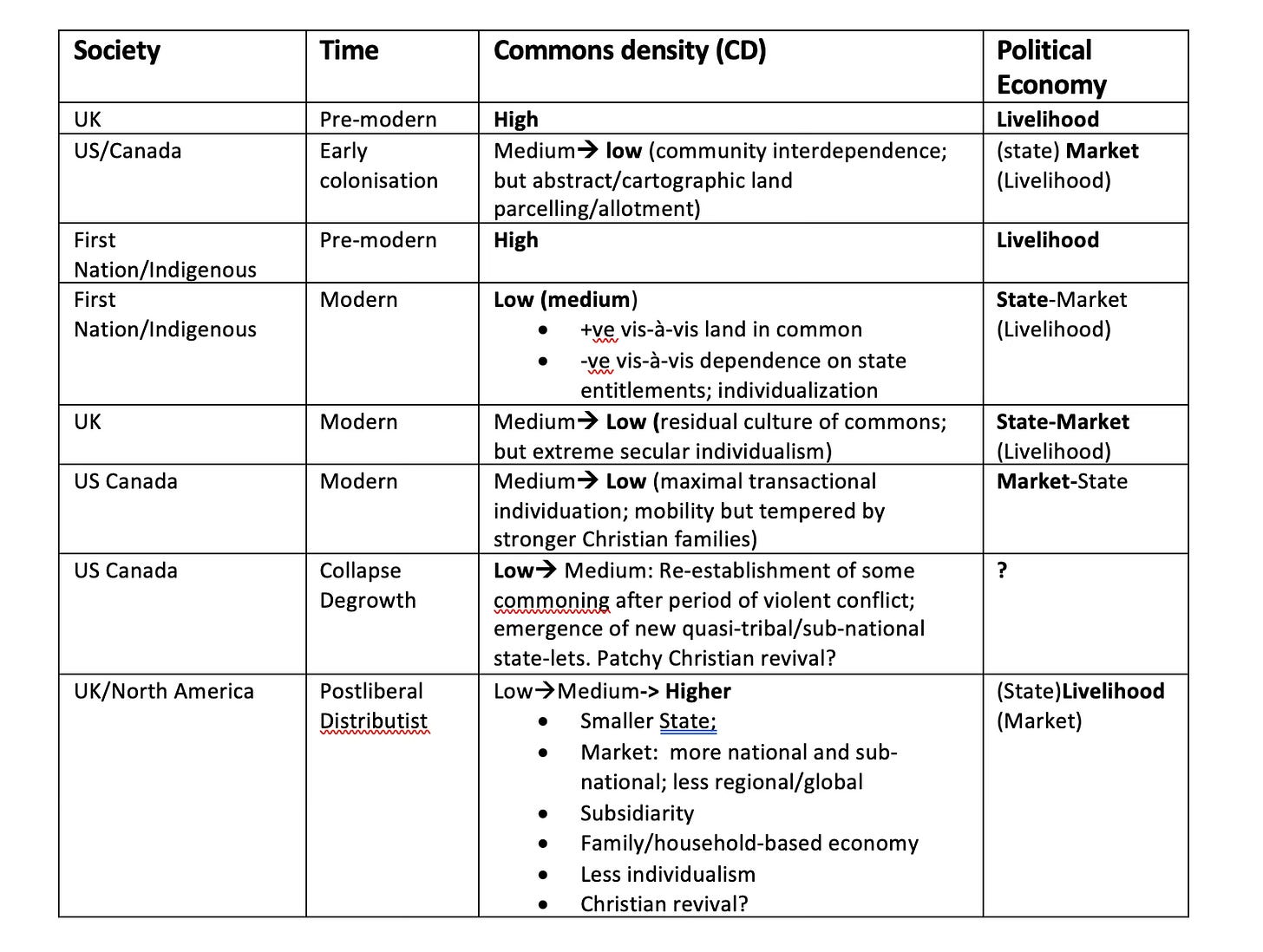

One way to think of this would be a notional metric of the commons density:

Social qualification (of transactional freedom) per person per unit area

More than a measure of say interdependency, this would refer to the density of cross-cutting easements, familial and kinship obligations, culture of hospitality and neighbourliness, conditional access rights, caveats, qualifications, usage restrictions, disposal-restrictions, covenants, social norms, cultural cycles, deep-seated habits of mind or any other formal or informal, legal/conventional qualifications impinging on a person’s capacity and propensity to dispose of territory or land-based resources – or qualifications per person, per acre. Critically this relates to bottom-up, non-state based and communitarian mechanisms, to some extent internalised into the habitus of well-formed individuals. Even for tightknit ranching and homesteading communities in the American west, this hypothetical metric would probably be lower than for a contemporary farmer in the UK – at least to the extent that there is still a residual familiarity with common pool resources (including common lands) which flows into the way that British people think about landscape, or wildlife or institutions as the National Trust and the NHS. On the other hand, rural Americans would likely score more highly with regard to psycho-social formation by Christian churches. This pertains to a notion of created or ‘habituated grace’ that was ironically rejected by Luther and most protestant denominations. Nevertheless, the capacity of a Christian community to work with God to created habituated dispositions which structure and inform our life in common and respond with individual acts of faith, hope and love was a preoccupation of medieval theology (Thomas Aquinas, ST, 1-2 q. 110 aa. 1-2). The tradition of the English commons or stronger American Christianity aside, the commons density metric is in both cases likely to be miniscule compared with just about any householder in pre-modern Europe, Asia or Africa.

The table is purely speculative and just meant to raise rather obvious questions about the impact of capitalist modernization on the societal commons.

With respect to the indigenous communities, the situation is more complex. The Commons Density is almost certainly higher in some respects. Reservations are by, definition, lands held in common, and their existence is a standing reproach to the wider society of private property and individuals. But at the same time, Native North Americans are moderns in every sense. They depend on modern technology. Their kids are doing the same social media and drugs as everyone else. They are dependent on individual wage labour, or individual social security entitlements. And family breakdown means that the tissue of kin-based reciprocation is in many instances weaker than in the wider community.

Ignoring such difficult realties, Craig Fortier asks what it means to ‘claim “the commons” on stolen land’ and then travels back in history:

‘ to show the ways in which radical left movements have often either erased or come into clear conflict with Indigenous practices of sovereignty and self-determination’.

The point of his argument is presumably to contest this habit of mind and practice on the part of the left and re-assert Indigenous practices of sovereignty and self-determination as the basis for a truly emancipatory politics, because:

‘there are multiple commons or conceptualizations of how land, relationships, and resources are shared, produced, consumed, and distributed in any given society’.

This is not entirely true – or at least it underplays the extent to which one way of defining modernization might be as the systematic reduction in the number and overlay of common pool resources and associated conceptualizations of sharing and relationality. There are certainly differences between societies. Nevertheless, it also points to a truth. In an age of ecological uncertainty and limits to growth, any truly localist politics would absolutely depend on the re-emergence of institutions and ontologies of shared access to and management of common pool resources. Just by way of practical examples one could think, for example, of basic income proposals, land-dividends, CSA schemes, the re-institution of foot paths and rights of way, new forms of welfare and security based on sub-national we-identities rather than the social/market contracts between the state and/or private companies.

Indigenisation: Be careful what you wish for

But this is of course dangerous territory. Any qualification of the sociology and ontology of individualism that underpins liberal politics, could radically undermine the social contract that underpins democratic polities. If place-bound tribes, or indeed any other forms of mutual identification, displace the nation-state as the primary survival units for people and families – and the main axis of resource allocation – then one can realistically expect conflict. The state’s monopoly of violence and the remarkable degree of passivity and the absence of inter-personal violence that defines western-type modern societies (Elias, 2012; Pinker, 2011), depends absolutely on the effective and legitimate role of the state in allocating resources between individuals through fiscal monopolies, organizing a range of services and infrastructures and containing market-led forms of social disorder.

Fortier’s radical path ignores this real-politic. He says:

‘As opposed to the liberal politics of recognition, a political practice of unsettling and a recognition of the incommensurability of political goals that claim access to space/territory on stolen land is proposed as a more desirable way forward’

It is not entirely clear what this means. However, it seems clear that starting from a premise of ‘stolen land’ is potentially disastrous. It rather depends on who it is conceived as being stolen from. There are a few conceivable trajectories:

1. Soviet style collectivization: In this case, land is conceived as stolen by capitalists from everyone and belongs in principle to all. Capitalist appropriation is an original sin against the commonwealth; and therefore, land should be nationalized and held in common. This implies a communist model with some kind of central planning. Successful completion of the requisite ‘class war’ (or so the theory used to go) would eliminate any intrinsic conflict between different classes of people. In fact, history is very clear that elites would certainly practice a kind of appropriation against the people; and further that in the end, economic dysfunction and inefficiency with regard to allocation would lead to disaster and genocide. Call me old fashioned, but I very much hope this one is a non-starter.

2. Indigenous repatriation: Land is conceived as being stolen by European settlers – requiring decolonization and repatriation of some kind. This seems to be the logic of ‘unsettling’ as conceived by indigenous activists and would of course be an absolute disaster in North America. By establishing two irreconcilable classes of commoners – a large class of settlers who are deemed morally tainted by sins of fathers; and a small class of indigenous people who are deemed virtuous on account of past victimhood – the scenario sets the stage for zero-sum and probably, in the event of real economic collapse and hardship, genocidal conflict. The idea is for stolen land might be physically returned is clearly preposterous and a non-starter. Following the logic of (2) above, one option would be for the state to pay an annual Henry George-style tax on all ‘stolen land.’ This could be distributed as a land dividend to all indigenous citizens as individuals; or transferred to the communities/reserves, to be allocated by First Nation polities /chiefs. However, in effect, this is what has been happening through the elaborate system of subsidies and ring-fenced funding – and both critics and advocates of the system are unanimous in their negative verdict as to the overall outcome after a century. After many decades this fiscal stream has done little to easy social problems (e.g. addiction, poverty, educational underachievement, sexual violence, ill health, suicide) or transform a situation of structural dependency. Critically, from the perspective of this essay, such funding has if anything weakened the family (as welfare has among poor white and black demographics) and strengthened bureaucratic state institutions at tribal, state/provincial and federal levels.

3. State fiscal commoning: Conceived as having been stolen from the commonwealth of creation (i.e. from everyone), all land is nationalised in principle but not in practice. Land holders have to pay annual tax, that is redistributed to everyone qua citizenship. This would be the model of basic income first advanced by Tom Paine in Agrarian Justice (but also William Ogilvie, Thomas Spence and many others since). It is also the cousin of the Social Credit scheme of Major Douglas, and of course the single tax of Henry George. This is radical, and maybe workable, and doesn’t necessarily conflict with the liberal principle of individualism and the imagined community of a nation. Because any payments are not means-tested and could be automated, a safety net based on these principles might be preferable to any contemporary welfare state. The much lower level of fiscal transfers would be balanced by the much less onerous state regulation and the incentives for DIY entrepreneurialism.

The second of these options underlies all discourses of decolonization – although they are always vague and unspecific. The issue is this. Let us just imagine that a radical political agenda in conjunction with ecological-economic crises, leads to the fatal undermining of liberal democratic nation-states. This would rather quickly destroy processes of political legitimation, which depend on fiscal transfers from a growing economy. Sustained economic contraction would unravel the social compact based on the state. The social contract that makes the nation-state possible is that people give up familial and clan-based survival units in exchange for physical and material guarantees from the ‘imagined community’ of the state. This imagined community was in turn made possible by the extraordinary impact of Christianity – codified by St Paul’s injunction that the Imago Dei was internal to every human being, qua humanity, and that care, nurture and safeguarding was to become a function of the wider community rather than narrow relations of kinship and patrimonial household. Without that, and especially in the context of secularisation and the loss of traction for Christian ideas and psycho-cultural formation, there could only be one result – namely the re-tribalization of our basic survival units.

Inter-Tribal politics in situations of demographic growth and land scarcity is always consistently, reliably a violent zero-sum. This was true when Saxons and Angles were moving into southern England from the 450s. It was true earlier when Celts moved into lands occupied by earlier Picts (pushed into the North-East of Scotland). It was true in the empire politics of the Incas and the Aztecs and at various times in conflicts between First Nations in Canada.

The third scenario would immediately raise the hackles of any red-blooded conservative or libertarian in the United States – perhaps understandably. But starting from the real politic of where we are – all nation states need some kind of social compact. A minimal safety net is a precondition for social cohesion and political stability. And to the extent that people have been deprived of their access to an independent means of production (land) it is also just. At the same time, the precise architecture of the social compact matters a great deal. This is mainly due to the differential extent that various systems can undermine natural mutual aid and reciprocation, disrupt family patterns, create perverse incentive structures and entrench endemic moral hazards. The real question is then how a minimal safety net can work with the grain of Natural Law and foster independence, self-reliance and mutual reciprocation from the bottom up.

Distributism -- or ‘Christian Libertarianism for Families and Communities’

The following principles are offered as a starting point for a political economy that is simultaneously libertarian and communitarian; and post-liberal to the extent that its starting point is not abstractly sovereign, disembodied individuals, but (to channel Alasdair Macintyre - Macintyre, 2001)interdependent, rational animals.

1. We need a civic-national state:

Any retribalization of politics and society would be a disaster. Practically it would mean a return to endemic conflict. Morally and ethically, it would mean losing the central inheritance of Christian societies which is the intuitive and common-sense recognition of Imago Dei – that every individual is sacred in the eyes of God. If war, energy constraints or a balmy politics of indigenisation saw the civic-national state disappear, this would effectively destroy all of the gains of Western civilization and the improvements in living conditions and governmental authority globally since the second world war.

2. We need a market society:

And just as we need the state, we need market society – some version of capitalism. The disembedding of society since the Early Modern period was responsible for many of the most pathological aspects of modern society including hyper-individualism, materialism, the mindless culture of consumer society, ecological destruction and the excesses of corporate capitalism. But it also generated the scientific advances and culture of technical innovation without which we wouldn’t have modern dentistry, medicine, transport and all the other mod cons which seem now to be so indispensable – certainly for those who don’t have them. Hayek’s critique of central planning centred on the distributed way that markets process and integrate information (about needs, wants, availability, stocks) – which is to say at the furthest ends of the capillaries of the virtually infinite transactional chains that constitute the global economy. It holds now as it did in the 1950s(Hayek, 1946, 2006).If anyone is in any doubt about the veracity of Hayek’s critique, they could do worse that read prominent New Left theorist Hilary Wainwright’s own critique of Hayek; a self-immolating riposte that effectively albeit unintentionally confirms Hayek and makes leftist visions of democratic planning seem childish(Wainwright, 1994).

3. We need the commons:

We need a culture that values and enlarges the commons because they represent the residue of an intergenerational life lived in common. Contemporary commentary focuses on ‘common pool resources’ which is to say, the economic aspect of this inheritance (Ostrom, 2015). But this is insufficient. Ostrom’s manifesto has little to say about managing anything other than small scale and very local resources. She greatly underplays the extent to which we need both the state and capitalist market allocation. But the material focus on energy and resources completely ignores the extent to which culture, psychology and the habitus that emerges with particular patterns of childhood socialization and formation are also ‘commons’ – emergent features of a society that are produced unconsciously and often unintentionally as a biproduct of a taken for granted way of life. In the West, the Judeo-Christian heritage that starts with the Ten Commandments, the Pater Noster and a guiding assumption of the Imago Dei are the basis for the most important commons of all. Moreover, it is precisely, and only, this wider legacy of common pool resources that can temper both the over-encroachment and formal rationality of both the bureaucratic state and corporate markets. In fact, it is only these commons that can allow us to take advantage of allocative efficiency of the market and the capacity of the state to marshal and direct resources without becoming subordinated to the dangerously imperial and sulphuric logic of either capitalism or the state.

4. We need Judeo-Christian Natural Law, and we need Jesus:

Libertarians have often imagined 18th and 19th century capitalism as a secular society of rational sovereign individuals that at least approximated to an unadulterated form of ‘classic liberalism’ that went off the rails with the emergence of the big state during the World Wars. But in fact, this heyday of capitalist individualism only worked at all to the extent that it was able to draw upon what William Ophuls ( 2011)called a lode stone of fossilised virtue inherited from a millennium of medieval Christianity. The corrosive force of self-seeking, materialistic market individualism was kept in check by the mesmerising force of the Ten Commandments and the moral force of Imago Dei. This moral aquifer is now empty. We are running on fumes with a corresponding escalation of social disorder and moral confusion.

Paradoxically, both this very market individualism and the legacy commons that we inherited from medieval society derive from the same source – the Christian Imago Dei. Qua humanity we are sacral individuals created in the image of God. But in Christianity, personal sovereignty involves a capacity for self-actualization in a very specific way. It’s not ‘you do you’ or ‘me-myself-I’. Freedom is not understood in terms of autonomy, but rather fulfilment through relation to God. This is a freedom of self-constraint. As every new mother understands, real freedom comes from pouring oneself completely into love for another.

Albeit incompletely and partially, such freedom is manifested also in the structure of mutual obligations and constraints that are internal to the architecture of the commons.

‘I will cross your land on a footpath; you will allow it, accept it freely; and I will respect your land and animals… will share in this common resource but not beyond my share or the level that the resource can withstand… We will agree together out of mutual courtesy to respect the peace and quiet of a Sunday morning (even if some of us long longer attend church)’

…and so on. And it is only this underlay of Christian virtue ethics – shared conceptions of what it means to be of good character and the kind of habitual individual and social habits through which this is internalized into our inner personhood – that allowed Western society to take advantage of the efficiencies of market society without the social order imploding. It is why medieval and early modern Europe was both dynamic, scientifically progressive and outward looking but also stable and cohesive, developing all manner of institutions and social innovations for looking after the most vulnerable in society. It is also why even Victorian liberal society at the apogee of capitalist individualism saw a resurgence of charities, guilds, friendly societies and other refurbished forms of medieval association (or the Txoko Basque cooking clubs I wrote about in an earlier post).

In short, only a Christian virtue ethics has the potential to:

Re-embed the transactional rationality of market society without relinquishing the efficiency of market allocation.

Generate a bottom-up, communitarian, autopoietic and generative pattern of mutual care that can obviate and restrain the need for top-down bureaucratic interventions, and limit to the scale and scope of the State in relation to both the Market and also the domain of Livelihood.

5. We need distributism:

So we need: a civic national state, possibly/probably with some minimal form of welfare safety net; a generous and dynamic lattice of cultural as well as economic ‘common pool resources’ which are recognized as such and cherished by most members of society; a healthy respect for free marketsprotected and sustained by appropriate legal systems, policing, social norms and culturally rooted habits of mind; and a Judeo-Christian culture of super-tribal individualism sustained by an active and hegemonic, exuberant and public practice of Christianity. But what does that look like in terms of political economy? Is that a right or left-wing economic project. Is that a materialist liberal growth project or an (perhaps inadvertently) green project of ecological self-limitation? What does this look like politically? Who are my friends and who my enemies?

Not (collective, abstractly conceived) means of production, but rather the familial/household means of familial autonomy

The answer, in my view, must look something like the distributism imagined by GK Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc and others building on the tradition of Catholic Social Theory. (Callahan, 2016; Gill, 2007; Mathews, 2010; Quilley, 2022; Salter, 2023; Storck, 2008). Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum (XIII, 1891) was a rear-guard action – an attempt to catch up with a modern world increasingly divided between right and left, capitalism and socialism, the corporate state and unfettered price setting markets.

In the early 20th century, distributism pushed in opposite direction to the seemingly inexorable trajectory of corporate and bureaucratic centralization. The decentralized vision of networked families and communities producing and consuming in the context of households and neighbourhoods, organising themselves as far as possible and the locus of government and regulation pushed down to the lowest possible level (subsidiary) – was at odds with the economies of scale and vertical integration that animated the second industrial revolution. In the 19th century British railway workers used to grow potatoes on railway embankments, and there has been a strong culture of working-class allotments. But for the vast majority, mass society unzipped the household as a locus of autonomous subsistence and creative social activity. For factory and office workers alike – commuting between home and work (or school, or university) – the ‘means of autonomy’ were monopolized not only by large corporations, but by the state.

One of the most pernicious features of mass industrial society was the hollowing out of the household as an integrated focus for production and consumption, as well as childcare and socialization, schooling, skills acquisition and learning, religious education and catechesis. The logic of functional zoning ran amok with children segregated into factory schools, production into factories and even domestic food processing devolving to supermarkets and fast-food outlets, maintenance and repair to throwaway consumables. Creating an increasingly intractable division between work and home, the new regime had particularly devastating consequences for women. Entering the workforce, they have been forced to balance, or even make an invidious choice between, career and family life. Along with the meaning crisis, the pathological autonomy of youth culture, narcissistic individualization and consumerism, this separation has been a major driver of women’s unhappiness and mental unhealth.

A century later, the picture looks very different. In many ways the centralization and gigantism of the economy has accelerated – with globalization, the Internet, incipient AI, leviathan tech companies, private sector space corporations etc – so much so that the logic of transhumanism presents a serious threat to humanity, body and soul. None of this bodes well for women, marriage, family, child rearing or any kind of sustainable decent society. If artificial gestation threatens to replace motherhood altogether, that’s pretty much game over.

On the other hand, those same technologies, for the first time in the technological age, are making conceivable the reintegration of production and consumption on a micro-scale. With 3d printing, household-scale fabrication, computer-aided design, micro-injection moulding, limitless online training and instruction via YouTube and myriad skills training sites, and even desktop synthetic biology – the household and neighbourhood-level and truly granular (if not cellular) circular economy is becoming a real prospect. This means that, for those who choose, a holistic and integrated household economy – the cycling of production, consumption, fabrication, repair, disassembly, reuse – may reverse the industrial era separation of work and home. The possibilities are much greater now than when Alvin Toffler first floated the idea of the ‘electronic cottage’ . As Kevin Carson (2010) has pointed out, at least potentially, every modern household has a massively capable and polyvalent means of production in the kitchen, in the garden, in the garage, in the shed, in the workshop, in the pond and in the woodlot. What is needed is a distributist political economy to unleash this potential.

With regard to some minimal safety net, some kind of minimal universal social dividend derived from a hypothecated land tax and justified/legitimated with reference to creation as a commonwealth, would serve the minimal requirements for a civic national welfare state. But virtually free to administer and without means-testing and bureaucratic strings, it would not undermine incentives, create poverty traps nor generate mission creep in the expansion of the bureaucratic welfare state.

Distributism as a vehicle for iconic markets rather than idolatrous materialism

But none of this works without the Christian understanding of freedom as voluntary constraint and self-giving: individualism that is intrinsically other-focused and communitarian. That is why distributism is well-described as a libertarianism of families and communities. The agent in question is not the sovereign individual of liberal imagination, but a ‘interdependent rational animal’ well-formed, catechized and ingrained with the expectation of ongoing mutual obligation and reciprocation. Only with such a political economy — more embedded in the Polanyian sense — would market allocation, trade, innovation and entrepreneurialism operate unfettered by regulation but at the same time in service to the non-materialist imperatives of the good, the true and the beautiful. To the extent that market exchange becomes not an end in itself, nor geared simply to economic growth and profit as an end in itself, but as a means for family and community fulfillment, they might be described as iconic.

References

Barfield, O. (1988). Saving the appearances : a study in idolatry. Wesleyan.

Barron, R. (2016). The Priority of Christ: Toward a Postliberal Catholicism. Baker Academic.

Berman, M. (1981). The Reenchantment of the World. Cornell University Press.

Berman, M. (2000). Wandering God : A Study in Nomadic Spirituality. State University of New York Press.

Callahan, G. (2016). Distributism Is the Future - The American Conservative. In American Conservative. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/distributism-is-the-future/

Elias, N. (2010) The society of individuals. University College Dublin Press.

Elias, N. (2012). On the process of civilisation : sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations. University College Dublin Press.

Fortier, Craig (2017) Unsettling the Commons: Social Movements Against, Within, and Beyond Settler Colonialism (Arbeiter Ring)

Gill, R. (2007). Oikos and Logos: Chesterton’s vision of distributism. In Logos - Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture(Vol. 10, Issue 3). https://doi.org/10.1353/log.2007.0025

Hayek, F. A. von (Friedrich A. (1946). The road to serfdom, by F. A. Hayek. G. Routledge.

Hayek, F. A. von (Friedrich A. (2006). The constitution of liberty. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315832081

Jones, A. W. (2017). Before Church and State: A Study of Socail Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St Louis IX. Emmaus Academic.

Kohr, L. (1986). The Breakdown of Nations. Routledge & Paul.

Macintyre, A. (2001). Dependent Rational Animals : Why Human Beings Need the Virtues. Open Court.

Mathews, R. (2010). Hilaire Belloc, Gilbert and Cecil Chesterton and the Making of Distributism. Recusant History, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0034193200012814

Milbank, John., Pickstock, Catherine., & Ward, G. (1999). Radical orthodoxy : a new theology. Routledge.

Oosthuizen, Susan (2013) Tradition and Transformation in Anglo-Saxon England: Archaeology, Common Rights and Landscape (Bloomsbury)

Ophuls, W. (2011). Plato’s Revenge : politics in the age of ecology. MIT Press.

Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature : the decline of violence in history and its causes. Allen Lane.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation. Farrar & Rinehart, inc.

Polanyi, K. (1957). Trade and market in the early empires; economies in history and theory. Free Press.

Polanyi, K. (1968). Primitive, archaic, and modern economies; essays of Karl Polanyi. Anchor Books.

Quilley, S. (2022). A Complete Act: Conservatism, Distributism and the Pattern Language for Sustainabillity. Challenges in Sustainability, Forthcoming(DOI: 10.12924/cis2022.090100XX), 1–14.

Rieff, P. (1990). Reflections on psychological man in America. In J. B. Imber (Ed.), The Feeling Intellect: Selected Writings(pp. 3–4). University of Chicago Press.

Salter, A. W. (2023). The Context for Distributism: In The Political Economy of Distributism. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.3485520.6

Scruton, R. (2013). Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously About the Planet. Atlantic Books.

Scruton, R. (2014). How to be a conservative. Bloomsbury.

Scruton, R. (2018). Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition. All Points Books.

Siedentop, L. (2014). Inventing the individual : the origins of Western liberalism. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Storck, T. (2008). Capitalism and Distributism: Two systems at war. In T. Lanz J. (Ed.), Beyond Capitalism and Socialism(p. 75). IHS Press.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae [Summa Theologica 5 Volumes, Fathers of the English Dominican Province, trans. ( Christian Classics 1981)].

Taylor, C. (1992). Sources of the Self: The making of the modern identity. Harvard University Press.

Taylor, C. (2018). A Secular Age. Belknap Press, Harvard University Press.

Tonnies, F. (1963). Community and Society. Harper and Row.

Trueman, C. (2020). The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism and the Road to the Sexual Revolution. Crossway Books.

Wainwright, Hilary. (1994). Arguments for a new left : answering the free-market right. Blackwell.

XIII, P. L. (1891). Rerum Novarum (Papal Encyclical).

[1] Lenin, V: A democratic republic is the best possible political shell for capitalism, and, therefore, once capital has gained possession of this very best shell (through the Palchinskys, Chernovs, Tseretelis and Co.), it establishes its power so securely, so firmly, that no change of persons, institutions or parties in the bourgeois-democratic republic can shake it’ The State and Revolution, 2018; Collected Works, Volume 25, p. 381-492

[2] There is a massive literature on this including Elias, 2010; Rieff, 1990; Siedentop, 2014; Taylor, 1992; Trueman, 2020)

I think you mean "anti-modernity," not "ante-modernity."

"Ante-" is a suffix meaning "before," as in "antebellum," meaning "before the war." It is the equivalent of "pre-," as in "pre-war."

If that isn't what you mean, I must confess that your usage is very confusing.