Apologies for not posting the last couple of weeks. I hurt my finger putting up sheep fencing and have not been able to type much. I am now finally getting around to writing, and I have two separate but related thoughts that I would like to elaborate, albeit briefly.

The first relates to the idea that the telos of Jesus’s life, death and resurrection, and of the Good News, must be towards a culture. Christianity was never an individual or small group proposition.

The second relates to post-liberalism and its relation to an antecedent liberalism. Rather than the new thing, or the new ideology, post-liberalism should be seen as akin to the architectural process of underpinning — providing a new foundation for — an old building. Specifically, it speaks to the necessity of renewing and replenishing the aquifer of shared Christian virtue and a shared understanding of citizenship without which Western liberalism cannot survive.

#1 - The City of God and the Christian Culture Debate

I'm interested in liberalism, virtue ethics and postliberalism (in politics and moral philosophy). In previous posts I have circled the way in which which modern democratic polities in the West depended on a pre-cognitive, pre-political shared consensus rooted in Judeo-Christian metaphysics; or as William Ophuls quipped, the West depended on the orienting moral compass engendered by a ‘lode-stone’ of Christian virtue laid down over the previous thousand years. Although depleting fast and almost exhausted, it is not true to say that it is non-renewable. But such a renewal would depend completely on the revival of Christianity — on a civilizational Christian culture.

The idea of a Christian civilization has become a staple of conservative and post-liberal critiques of liberalism and globalization, as well as the more general right wing, nationalist and populist currents intersecting at the recent Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC) conference — with significant voices including Douglas Murray, Jordan Peterson, Ayan Hirsi Ali. The repetition of these names has itself become something of a cliche.

In his Surprising Rebirth podcast exploring the current revival moment, Justin Brierley has also interviewed many Christians —

and come to mind — who are cautious and perhaps even anxious about the overlay between Christian revival and the political project of cultural renewal. But it’s hard to see how any Christian revival amounting to more than an endless series of martyrdoms and moments of individual redemption could fail to aspire towards an encompassing shared culture — which includes not just liturgy, hymns of worship, but a cycle of holidays, patterns of work, literature, musical conventions seeping into popular sphere, a shared and taken for granted ritual repertoire, art, architecture and an implicit ‘pattern language’ for building villages and cities. The culture of medieval Europe didn’t emerge from nowhere. It was one singular but world-changing incarnation of a telos that is built into the logos. The alms houses, hospitals and monasteries, the gradual consolidation of the idea of individual human dignity in law and even the slow but inexorable movement towards legal and eventually democratic constraint of political power — all of this depended on Christianity operating at scale, to become a civilizing force. Messy, corrupt, sinful for sure. But infinitely better than anything that preceded it.Augustine’s City of God was a critique of the earthly city in which people abandoned themselves to the sinful pursuit of passing, material pleasures in this world. But his counterpoint is still a city; it is still a life lived in common by people who forgo earthly pleasures, dedicating their lives to the transcendent truth of God, revealed through Christian faith. The City of God surely implies a Christian culture, in which children and neighbours are socialized through recurring patterns of interdependence — by being caught up in the same hymnal refrains, praising God and manifesting obedience and gratitude by love of one another.

From this perspective, Christian culture and civilization is the telos of shared faith. The project of civilization is certainly messy and the narrow gate in such circumstances more elusive. And when extant civilization has fallen so far, it is necessary sometimes to withdraw and focus on the more certain probity and integrity of what

refers to as wild Christianity. Such a response goes back to the Essenes in Biblical Israel, and to the Irish and Northumbrian Christians during the early Christianization of Atlantic Europe, and later to the Dominican and Franciscan challenges to the ossification of the Church in the 12th and 13th centuries, and of course to the crazy kaleidoscope of the post-reformation purity spiral that produced all manner of metaphysical life-boats seeking to realize the City of God in microcosm.I’m very grateful that the mood among Christians seems to be focusing on mutual support rather than sectarian conflict. None of us know God’s purpose or the details of his plan. Perhaps it is better that we see the theological tacking and the work of different denominations as having some dialectical purpose for each other — each providing some thread in the broader tapestry. The same can be said for developments and course corrections over time. Catholic traditionalists might rail against Vatican II. But I rather think Bishop Barron’s intuitions are probably correct. The present moment might require a sustain ‘conservative’ course correction. But it would be a mistake to think that the Church will not be carrying forward and building on some of the accommodations with modernity that took place in the 20th century. The young veiled traditionalist women thronging to TDM present (to my mind) a much needed rejection of just about every theoretical and practical innovation of 20th century feminism. But the women themselves seem to carry a spirit and an energy that is different and dare I say, stronger and more emancipated than the post-war generation of their great grandmothers.

I suppose, taking to myself, another way of saying this is: Yes I should get involved in Christian politics. But, I should resist the temptation to swing between the affective poles of euphoria and dismay with every encyclical twist and turn. God does have a plan. He won’t renege either on his covenant with Israel or that with the New Israel. Politics is part of the human condition.

#2 Postliberalism is the new foundation for liberalism

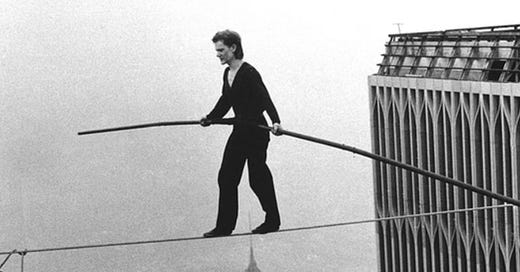

Post-liberalism is not ‘after’ liberalism. It doesn’t supplant or replace liberalism. Rather, we are still all liberals (even if many on the left have forgotten). However, ‘liberalism’ can’t exist as an ideal type, on its own terms, and never could — any more than lions can exist without the endless horizon of grasslands and huge herds of herbivores. Classical liberalism depended on an unrecognized lode stone of Christian virtue inherited from Christendom. The story it told about individual rationality and choice was always a fiction. The kernel of truth — the transcendent nature of human dignity and freewill — derived from the Christian Imago Dei. But once this genealogy became too embarrassing; once the smart set of liberal intellectuals dreamed that they could go it alone — the reality of Christian foundations and an inherited reservoir of intergenerational and socialized virtue became invisible. The undergirding was pre-political, and precognitive. It framed ideas of political justice, psychological need and defined civic common sense. But as the sea of faith retreated the role of this reservoir of shared virtue became largely invisible and faded from consciousness — particularly among intellectuals. The effect was rather as if a high wire artist suddenly lost sight of the wire and convinced themselves that they could fly.

The effect was rather as if a high wire artist suddenly lost sight of the wire and convinced themselves that they could fly.

A century later, shorn of the girdle of faith, liberalism is dying. I won’t reiterate the thousands of examples that are flagged on Substack and twitter every day: two tier justice in the UK; the aggressive suppression of free speech; the banning of political parties in the EU; the lowering of thresholds for political violence. Perversely — and apparently unaware of what they are doing — the same progressives who used to cherish freedom of speech and association are now aggressively attacking Christian culture in an increasingly overt culture war, whilst seeking to expand the demographic weight and civic presence of Islam — a religion explicitly predicated on denying the most basic freedoms to women and other minorities. So much, so paradoxical.

In this context, post-liberalism can be seen as one part of the liberal polity seeking to reorganize the system having finally recognized the necessary link between traditionalism, Christianity and any version of modern individualism that is sustainable over the long term. This is something akin to the top half of an ocean liner recognizing that it has a keel — and understanding the extent to which its orientation and movement depend on structure that is below the waterline.

Postliberalism is then an attempt to resuscitate liberal individualist modern Western cultures by re-girding it — something like underpinning an old building with new foundations. The difference is that the new foundation must be conscious, deliberate and actively created. There is a clear danger in this. As modern architecture demonstrates, no amount of planning and expert design can easily reproduce the natural, organic and unconscious beauty of urban environments that evolved slowly over hundreds of years. On the other hand, we are not building from scratch. As the renovation and rescue of Notre Dame Cathedral showed, near disaster and resurrection can demonstrate that the ‘new skins’ bequeathed by the Church fathers are still new, and can and must be renewed with each generation.

Cultural christianity and culture war

Elsewhere I have been exploring the wicked trade-offs between increasing diversity, social and spatial mobility and individualization on the one hand, and solidarity and social cohesion. Since the French Revolution, radical progressive politics has followed a utopian path, predicated on the assumption that an abstract universalist conception of human nature can be realized over and above actual, place-bound political communities. This attempt to create 'Heaven on Earth' on the basis of a secular, materialist metaphysics and divorced from any transcendent pattern of restraint (to 'immanentize the eschaton' as Voegelin quipped) invariably led to genocidal, totalitarian disaster and has cost hundreds of millions of lives.

In contrast, where more modest liberal-democratic projects held sway, political liberties, relative consensus and taken for granted freedoms of association and expression have relied on more than common law and formal laws or constitutional protections. Such formal mechanisms have only worked in the context of a largely unconscious, reservoir of shared virtue (moral ideas but also habitus and taken for granted practices) inherited from traditional society. The polarization of western societies associated with 'populism' — the tension between metropolitan, 'globalist' liberal elites on the one hand, and provincial, working class communities on the other — is to be understood, in part, in terms of the draining of this non-renewable resource and the collapse of consensus. Rooted in the tradition of social catholic thought derived from Pope Leo XIII, postliberalism is an attempt to to reforge the pre-cognitive, pre-political moral consensus that is a prerequisite for the more limited domain of liberal freedom.

The main issue is just patriarchy or lack thereof.

https://blog.reaction.la/culture/how-to-restore-a-reproductively-successful-society/