A doctor friend was musing about the extent to which it is possible to work within the system, without becoming conscripted unwillingly into a well-meaning war against Divine Law – an unwitting temple priest for the new idols. From abortion to voluntary euthanasia and sex changes, the swathe of policies and technological possibilities are part of the unfolding story of Genesis. But it’s not just the hubris of mercy killing. It’s also the privileging of life per se over good living, of this world over that to come. The more that we can do, the more we will be tempted to do and the more we are tempted to decide for ourselves what is right and wrong. And when you put it in those terms, it’s obviously impossible to tell where we are overstepping the line and arrogating decisions and powers that are not ours to dispense. I guess that is the point.

The choices may seem clear cut. But in practice we are all implicated ipso facto as denizens of modernity. Increasing longevity is a function of reliable food systems and better nutrition, but also a proliferating network of detached cognitive models of how the world works (medicine, public health, surgery, vaccines), and economic systems that produce sufficient surplus to make possible welfare safety nets and an array of para-medical specialists ready, blue-lights flashing, to postpone the reality of our mortality. We don’t live forever, but increasingly, we act like we do, or we might, and perhaps we should. Whether the primal act of animal slaughter and meat processing, or funeral rites, the technological mediation of modern warfare or the invisibility of bodies, death is screened out of our daily experience. Modern people are unfamiliar with corpses and killing; we are psychologically distanced from the reality of finitude.

At the same time, our aging and insulated demographic now has to accommodate new and unpalatable forms of suffering. The tail-end of long life is often debilitating and marred by chronic pain, incapacity and loneliness. But the loneliness of extended living-dying is also paralleled by new pathologies of youth. Freed from the exigencies of the dull grind of lifelong physical labour and trapped in an ever-expanding teenage half-life between childhood and parenthood, young people are mobile as never before. Is it really surprising that this condition of what Zygmunt Bauman called ‘liquid modernity’ – the plastic, malleable, formlessness of social roles and expectations, the condition of permanent social and spatial mobility, go anywhere, do anything, be anyone…all of this unrelenting choice, actually makes people crazy, sad and chronically depressed? The Trans phenomenon is really only an extension of anorexia, bulimia, ADHD, depression, drug-induced apathy, obesity, nature deficit syndrome, peer-group socialization, and teen sexualization – a kind of generalized youth pathology syndrome, and very much a function of the unhinging of the modern self.

Having killed God, the ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’ of a world without Faith leaves these long-lived depressives, young and old, increasingly dependent on the soma of ubiquitous pornography, compulsive Internet addictions, meme-tiks and government sponsored soft drugs. Little wonder that the global market for therapy reached over $10 billion USD in 2024.

This ‘triumph of the therapeutic’ is not just an expression of the reality of suffering. It is the modern secular denial that suffering is a necessary part of life. In the utopian impulse that sprung from the Enlightenment disenchanting of the world, the serpent’s whispering suggestion that Adam and Eve could become masters of their own destiny, has, for moderns, become a deafening clamour. Modern secularism is above all an attempt to create heaven here on Earth – a project of time and space in child-like defiance of entropy and biophysical limits. This revolutionary utopian desire to ‘immanentize the eschaton’, as Voegelin quipped, has always been catastrophic. If there is an iron law in history, it is that utopians who get their hands on the levers of state power will always fail with genocidal consequences.

Are we all now Gnostic revolutionaries?

It's easy to point the finger at Red Guards, sans culottes or Bolsheviks, and of course the ultra-progressive woke revolutionaries on TikTok. A little history and the palpable absurdity of their claims make intellectual ‘debunking’ child’s play for any would-be Ben Shapiro. What is harder to debunk is the extent to which all of us are born of and conform to a pattern of life that is built upon that same child-like defiance. To some extent, we are all Gnostics, shaking our fist at God and determined to self-determine through mastery of material creation. In a small way, we commit to this every time we take an aspirin, or drive a car, let alone seek medical fertility interventions, blood thinners or the myriad financial instruments that promise to extend our glory days well into our 80s, 90s and perhaps beyond. A hundred times a day, we manifest our lack of trust, our bad…or let’s say faltering and incomplete… faith in God. We privilege this world over the next, and we cling on to what we have above any promise of the world to come.

Of course this is easily said. When Jesus replies to the young and faithful follower who happens to be rich, ‘no problem – all you have to do is give it all up and follow me!’ (Matthew 19:21-24), he’s setting a tough, and perhaps impossible, target for us all. It certainly feels impossible to me – and to be honest, internally contradictory as well. How could the young man honour his mother and father, and his obligations to family members and neighbours, by choosing a life of poverty and abstinence? Would it be right for me to choose poverty and suffering on behalf of my wife and children? And so, with some intellectual gymnastics, I stand exonerated and can carry on, in this world, bogged down with material cares, but …for now …fairly comfortable.

Putting aside that very high bar, what about a doctor who is asked to refer a patient to an abortion provider or for a MAID assessment? What about the myriad ways in which we all compromise with an aggressively progressive social order in order to get by: the schoolteacher who acquiesces to the ubiquitous Pride flags; the university professor who creates an absurd DEI statement in order to apply for a research grant; the lawyer who cooperates with the prosecution of a male rapist as a legally certifiable woman; each of us who structure our lives and finances with iPhones, digital money, facial recognition systems, social media and now burgeoning virtual realities?

Do we live in the neighbourhood of Babylon or within the city limits? This question is as old as Judaism and likely it will be with us until the second coming. Babylon was a particular place – of exile. But it is also a geographical and social manifestation of the internal exile from God that has been with humanity since the fall. Babylon is Augustine’s ‘City of Man’. For the Jews, the second exodus took place when King Cyrus of Persia overthrew Babylon and decreed that they should be allowed to return home. Led 900 miles back to Jerusalem by Ezra, Israel was able to rebuild the Temple and re-establish proper worship of God. But no more than Moses, was Ezra able to banish sin and restore Edenic harmony. Over the next 400 years the familiar patterns of individual and social corruption re-established themselves. You can take people out of Babylon but not Babylon out of the people.

The question of how to live in Babylon – a society that has turned away from the Lord, abandoned intuitive tenets of Natural Law and constructed institutions mired in the idolatrous presumption of self-determination – can’t be separated from the question of how to navigate the Babylon that has made its home within us. Superficially this is a question of glass houses and throwing first stones. But more fundamentally it is about how to confess and to take communion honestly, whilst knowing simultaneously that our sincere aspirations to be better will continually be confounded.

Purity and Separation: The Pharisaical route.

One point of departure is surely doomed to fail. This is the absolutist path of binary judgement that is the rhetorical favourite of argumentative teenagers and was the way of the Pharisees. ‘Here is the standard. Here is the yard stick. Let the winnowing begin.’ The implication is for Christians to set up shop entirely independently of mainstream society and for the elders to police standards of purity of thought and behaviour that sharpen the distinction between Christianity and other creeds, especially that of woke progressives. They are not wrong about the standard, but not even God anticipates saintly perfection on command. This is why salvation centers on forgiveness. Jesus’ mission itself focused on the gap that opened between Pharisaical attention to the law and God’s commandment to love. God’s love is the reason that we have free will – and as the covenantal history of the Bible shows rather clearly, as with the parents of that teenager, God is in it for the long haul.

The Benedict Option

Another is to recognize, like Alasdair Macintyre, that virtue is a habit of body and mind, and most easily nurtured in the context of like-minded communities, shared practices, taken for granted rituals and God-seeking communities. This is the operating rationale of the monastic tradition first codified by Benedict of Nursia and dusted down recently by Rod Dreher in his manual for Christian families exiled in the Babylon of modernity. The Benedict Option has much to recommend it and, at the very least, clearly articulates a problem that is urgent and familiar for every Christian parent surrounded on all sides by shopping malls, ubiquitous Internet-broadband, soft drugs and in-your-face woke Pride.

The Benedict Option is also the logical extension of the pattern of life that my wife and I stumbled into quite by accident. Having moved from the most secular, ironic, cynical and effortlessly post-everything instantiation of Babylon that is modern Britain, we ended up homeschooling our four children among an ecumenical mix of Christians, in rural Ontario. Intentionally choosing your friends, your network of families, the pool of child-friends, allows at least some control over key decision points – such as the age at which children get mobile phones, or the likelihood of their being exposed to pornography or drugs. For mothers, and perhaps more so for fathers, it generates more compelling structures of behaviour and mutual restraint as to the acceptability of norms or habits of mind which are otherwise routine in wider society. It has taken a long time, but I’m beginning to drink less than is normal in my native Newcastle upon Tyne.

Demography and the woke apocalypse

Trump’s victory and populist hiccups notwithstanding, short of a massive evangelical tide emerging from nowhere and replicating Martel’s victory at Tours in 732AD, Western civilization is going to fall into some kind of abyss. The passive but inexorable forces of demography alone are likely to see parts of Europe, starting with the United Kingdom, succumb to Islamification within my own lifetime. This is not just because of migration and comparative birth rates. It is also because Islam has shown itself to be aggressive and uncompromising in its approach to proselytization, and canny in managing the politics of such hostile societal take-overs. Once a small minority becomes a large and cohesive block comprising of more than quarter of the country, you can expect the tactical emphasis on human rights, cultural respect, diversity and multiculturalism to give way to a much more overt projection of political and territorial power – council by council, city by city, state by state. This pattern is not new. In Europe, in the coming decades, Babylon is about to get overtly theological.

The most bizarre aspect of this implosion of the Judeo-Christian West has been the collusion between radical Islam and the most demented vanguard of Enlightenment progressivism in the form of woke politics. Although, Trump’s victory makes it possible that the extremes of DEI identity politics will be rolled back in corporate board rooms, the public sector and in particular the universities and schools will be a much harder nut to crack. In his second book Live not by Lies Dreher channelled Solzhenitsyn (and here) and echoed Jordan Peterson in emphasising the truth as a universal solvent. If the history of the early Church is anything to go by, Dreher, Solzhenitsyn and Peterson are all absolutely correct. A widely practiced habit of unflinching truth telling has moved mountains in the past and, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, was sufficient almost in itself to capture the Roman empire and almost the entirety of the known world. It’s dangerous. It incurs terrible costs – including death in parts of Africa and the Middle East. Here in the West the pain is gentler and the temptations for intellectual corruption more banal. But refuseniks can expect at the very least some combination of professional suicide, cancellation, loss of income, public shaming, arrest for ‘non-crime-hate-crime’ (in the UK), law-suits and financial ruin (Canada; UK) and loss of relationships and long-nurtured friendships (everywhere).

One unintended result of the social cancelling and ideological sorting of friend groups has been a collapse in societal solidarity – and what Robert Putnam called bridging social capital linking diverse constituencies – and a level of political polarisation that seems now entrenched in all Western societies. Apart from anything else, this makes it much more difficult for such polities, in the face of economic stagnation and rising geopolitical threats, to legitimate the kind of fiscal transfers that made possible the Keynesian welfare state. This problem is becoming much more acute as mass migration and enforced diversity undermine shared cultures and patterns of mutual identification that took centuries of violence, coercion and cultural innovation to create. The habit of iconoclastic destruction of national imaginaries that is second nature to the progressive left simply accelerate this societal implosion.

An upside of ideological sorting?

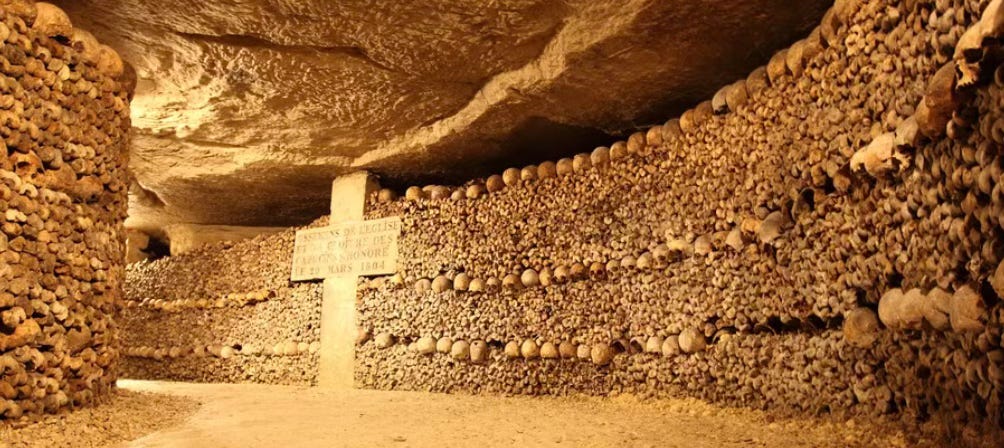

On the other hand, one small positive outcome is that those remaining Christians (and Jews) are becoming less divided along denominational lines and more conscious of their own evangelical mission as an embattled minority. Losing well-meaning and fundamentally decent but simultaneously sectarian and intolerant secular friendships is devastating. But at least it has the effect of consolidating the mutual identification with, and solidarity among, those who are otherwise isolated in the cultural catacombs.

Suffering and a quest for meaning cannot be sated

It is a cliché of cultural commentary that modernity has involved disenchantment. Max Weber coined the term as a play on Schiller’s idea of scientific modernization as the ‘de-godding of nature.’ But as many are observing, Western secularism seems to have run its course. G.K. Chesterton’s quip that unbelief in God opens the door to belief in ‘more or less anything’ turns out to have been characteristically on the mark. The highpoint of self-conscious atheism as a creed (the ‘New Atheism’) seems to have come and gone with Christopher Hitchens and the so called ‘four horsemen’ (Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris). In the wake of the apparent triumph of atheism, the undergirding of the woke apocalypse has seen the drowning of scientific rationalism in a soup of inchoate New Agism and barely concealed Paganism. Late-modern societies have seen a pronounced re-enchantment that speaks to the God-shaped hole in the human psyche but is informed not by the monotheistic Abrahamic tradition of the West but an incoherent grasping towards what Owen Barfield described as the ‘participating consciousness’ forever out of reach for literate, individualized, Cartesian ‘thinking statues’ produced by modern societies. Following Pascal, the vain attempt to fill this hole is the root cause of all idolatry – including the archetypical sexual and materialist pathologies of modern consumer society.

“What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.”

- Blaise Pascal, Pensées VII (425)

In his third volume, Living in Wonder, Rod Dreher embraces the perspective of Christian Smith who construes the empty enchantments of the New Age and occult as ‘moralistic therapeutic deism.’ Drawing on interviews with over 3000 American teenagers, Smith discerns a widespread form of soft deism in which the prime imperative is for people to be kind to others whilst self-actualizing and feeling good about themselves. God is undemanding, everywhere but uninvolved and largely confirming of comforting ideas about the primacy of self.

Pragmatic, instrumental and devoid of serious moral dilemmas, this new Babylon offers the same kind of soft-pile recipe for satiating human appetites as Huxley’s Brave New World – anodyne pleasure without guilt and above all an absence of passion – because the root of passion is some kind of suffering. And with suffering we arrive right back at the paradox that defines our humanity. To be human is to suffer. And to be the most perfect human, Jesus embraced and suffered the definitively excruciating death. Any societal vision that tries to eliminate suffering altogether, whether driven by a hubristic Enlightenment rationalism, a self-adulating therapy culture or the empty woo-woo pieties of modern spiritualism, will, in time, generate an unimaginable world of painful hopelessness.

Embodiment

It is for this reason, as Dreher observes, that the Christian West must re-centre a theology of the body – or rather of bodies. Embodied Christianity must celebrate the sensory and sensual delights of living here and now, in this world – in community with others and in communion with God. The bells and whistles of pre-Reformation ritual and liturgy emerged over centuries as a confluence of bodily conformation, social formation and communitarian togetherness. Kneeling, smelling, candle-lighting, processing, hand holding, singing, chanting, contemplating colourful statuary and icons, breaking bread, feasting, the mystery-play cycles, tramping the parish bounds, bell ringing, marking the anthropological rites of passage (the making of young men and women, catechumens, priests, graduates, guild members, citizens) along with the sacraments – these are all social-psychological technologies of the spiritual body. They draw individuals and groups into healthy social juxtaposition, into relations of communitarian obligation and respect for each other, and into spiritual relation to God. But by habituation and repetition, they also weave these relationships of mutuality and obligation into the warp and weft of body and mind – a fabric of automatic, precognitive and mostly unremarked expectations and reciprocations.

A central motif in this new embodied and communitarian Christian understanding of what it means to thrive is clearly a celebration of the granular quality of a life-in-relation. This is nothing new. It means the finding of joy not through acquisition, control and outward signs of material success, but rather self-restraint, giving-receiving, self-sacrifice and generous relation, otherwise known as love. But this joyful and loving approach to living, must also inform an acceptance of the unavoidability of suffering and in the end an acceptance of finitude that allows letting go – of things, of people and eventually of life itself.

Of course, this is easy to say – by someone who has been blessed and suffered little (at least by comparison with many in this world). It is nevertheless true. I don’t know whether it is possible to forge a technical civilization which engrains this capacity for relinquishment. For 70 years, ecological economists such as Herman Daly and (Orthodox Catholic) E.F. Schumacher have pointed to impossibility of never-ending growth. For Schumacher societal self-restraint was an unavoidable consequence of Natural Law and an equally compelling corollary of Divine Law. And yet economic growth is the motor that drives innovation, employment and the fiscal transfers which make possible the entire fabric of modern civilization, including the welfare state. Eventually, biophysical constraints will kick in, and growth will end. At this point the Gnostic-inflected materialism will implode of its own accord. Until that point, Christians must work towards forms of political economy that leverage (albeit more embedded) markets and channel capital without uplifting idolatrous forms of consumption and leisure. Part of this involves avoiding the denial of death and cultivating a renewed acceptance that suffering is part of the human condition. We should strive to ameliorate pain whilst avoiding the utopian temptation to abolish it.

Political polarisation and Christianity as counterculture

The current political polarisation, the sharpening civilizational threat represented by mass migration and Islam, geopolitical tensions with China – all of this creates an opportunity for Christians. Secularism and the constant cycling of the Gnostic materialism have not run their course. But the pragmatic centre-ground of liberalism is giving ground. Gathering pace during covid, there has been a steady stream of high-profile cultural commentators embracing Christianity, usually very publicly. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Mathew Crawford, Jordan Peterson and Jonathon Pageau are among the list, as well as Brits Louise Perry, Russell Brand, Paul Kingsnorth, Martin Shaw, Tom Holland and Niall Ferguson. These converts from the United Kingdom are perhaps the most significant because they come from the most secularised society in history. It’s hard for North Americans to grasp the depth of British scepticism and unbelief. Mathew Arnold mourned faith in God. Cultural commentators now mourn belief in even the idea of Britain, in the West and even in science, let alone progress. In fact, it’s difficult to think of any set of shared beliefs and values that constitute a national way of being. And so perhaps it is not surprising that out of nowhere, it is becoming acceptable and even just a little bit cool to be a Christian. Christianity is now the dynamic counterculture.

Peter and Paul set up shop in Rome because it was the cosmopolitan centre of the world. Faced with waves of brutal persecutions, Christians and Jews constructed 40 underground catacombs involving 150 miles of tunnels. As well as burying their dead the subterranean network provided a focus for decades of cooperative activity – physical labour, ritual procession, prayer, eucharistic liturgy, feasting – consolidating the Church as a unified entity, the body of Christ. The catacombs saved and perhaps helped to create European Christian culture.

If Christianity is once again threatened with eclipse and Western civilization in danger of demographic and cultural collapse, we probably need a new network of catacombs. If not tunnels and priest holes, then what? What might constitute the filaments and arteries of a dynamic new Christian counterculture? How should Christian families organize themselves? How should they engage with institutions now wholly captured by progressive ideologies? How should they evangelize? How do they ensure that their children are formed in the faith are able to find marriage partners and go on to have (many) children? How should they engage with politics? How should they form communities? And in what ways should the economy be bent to the arc of faith?

I’m going to be mulling these questions as a historical sociologist, as a Catholic convert, a fan of traditional music and dance, a rather useless hobby farmer and shepherd, an English ex-pat, a parent and hopefully at some point, a grandparent. I’m going to try and publish an essay a week, circling around these problems. If I come up with any useful ideas, you will be the first to know.

Great writing, thank you.