On statues, slavery and retrospective morality: Or how to make the sanctity of individual human beings, once again, inconceivable

An essay from June 2020 at the height of the George Floyd derangement

In 2018 an H.M. Treasury tweet made the claim that: “Millions of you [i.e. UK Tax Payers] helped end the slave trade through your taxes...In 1833, the British government used £20m, 40% of its national budget, to buy freedom for all slaves in the empire. The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Abolition Act was so large that it wasn’t paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.”

This claim horrified Kenan Malik. Writing in The Guardian, he pointed out, correctly, that although the slave trade itself was abolished in 1807, it was only the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act that, as the name suggests, actually abolished slavery itself. He went on to argue that the claim that British taxpayers helped “buy freedom for slaves” was mendacious and wrong. The money paid by the Treasury at the time (£20m – about £16bn in today’s money) was, he claims ‘not to free slaves but to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners as “recompense” for losing their “property”. Having grown rich on the profits of an obscene trade, slave owners grew richer still from its ending. That, scandalously, was what the taxpayer was paying for until 2015.

Malik goes on to castigate the government for having the temerity to play down the British role in the transatlantic slave trade, while claiming credit for ending slavery. ‘It was not Britain but slaves themselves and radicals in Europe who began the struggle against enslavement’ he argues. It is obscene, argues Malik, echoing historian Kate Donington, that the “moral capital” of abolitionism is still used as “a means of redeeming Britain’s troubling colonial past.”

But this argument is completely specious. The word ‘to’ (‘free slaves’; ‘line pockets’) refers to motivation. The Act was motivated by the settled will of parliament to abolish slavery. The £16bn did ‘line the pockets’ of former traders and owners. But it also did free the slaves. That’s what it did. ‘Lining pockets’ was a pragmatic, side-effect of the primary motivation. Without this payment, there could have been no consensus and emancipation would have generated seismic political violence and instability. What Malik and Donington are really cross about is that abolition didn’t take the form of a violent, bloody insurrection in which Nemesis flew down to take cosmic revenge on the perpetrators of a self-evident cosmic wrong. Instead, there was a classic British institutional fudge that had an immediate positive and unprecedented impact on millions of lives and the consolidating political-economy, culture and moral foundations of dozens of future independent nation-states in the making – but avoided an insurrection, mob violence and institutional carnage. It did also lead to transfer of money to slavers. This was not, however, what it was ‘for’.

Had he been there, Malik would presumably have preferred the ideological purity and rhetorical consistency of a French style revolution, with justice, tribunals, comprehensive new laws. But the Jacobins, in the end, reneged on their commitment to end slavery, killed millions in a cycle of devastating wars, and were responsible for a decade of genocide which established a pattern for every subsequent episode of modern revolutionary violence. The French revolution provided a reservoir of very bad ideas for generations of subsequent revolutionaries (including our own #Antifa). But for all the rhetorical blather, it was the Royal Navy, and not Napoleon’s revolutionary armies, that saw and end to slavery across most of the world.

For sure, any modern sensibility would have had those slave owners/traders prosecuted for breaking the law, acting in an appalling way and committing ‘crimes against humanity’. But that’s the point. There did not exist such a modern sensibility...because that is, well, modern! There were no such criminal statutes. The abstract, universal idea of humanity was still only gradually percolating, from its Christian roots, into a practical vision of society. For sure, there was a growing minority opinion from the 17th century that saw slavery as wicked and incompatible with Christianity – as there had been a few lonely early Church father voices raised against the Roman institution of slavery. But for this sensibility to flourish and become hegemonic, required what Elias (2010) refers to as a ‘Society of Individuals.’ Such a society needed the idea (from Pauline Christianity), but also the emergence of a complex society of socially and spatially mobile individuals. It’s almost impossible for people in modern societies — societies in which the prevalence of such individuals, each animated by that sometimes slightly schizophrenic internal voice, are taken for granted — to imagine a more embedded, communitarian, deeply participative society. We experience, naturalize and project such interiority.

But in traditional societies, where most didn’t even have individual names, monks would struggle even to read quietly ‘in their heads’. There was barely such a thing as an individual identity. People were construed, by themselves and by others, as rather passive functions of an ascriptive, corporate identity (family, clan, place.....and sometimes race).

In short, although Saul of Tarsus, as a result of his epiphany on the road to Damascus, arrived at an insight that we would recognize as something akin to the idea of individual human rights — it took 1900 years before Tom Paine could turn this this revelation into his best-selling The Rights of Man (see Lynn Hunt’s The Invention of Human Rights) – but only a few more years for Mary Wollstonecraft to extend the idea to women (even though Jesus and Paul had already got there also). Along the way, there was a move away from chattel slavery in Europe which was replaced by the more humane compelled labour associated with the feudal estate. But there was no universal concept of human rights. Across the world slavery and/or other forms of compelled labour remained, necessarily, the backdrop for any kind of societal complexity.

The point is that change is slow. And once changed, it’s hard and often impossible to think our way back into someone else’s shoes. Owen Barfield quipped that learning to ride a bike was easy compared with the impossibility of unlearning to ride a bike. Human rights is now, thankfully, a bike that we have learned to ride. It will take a great deal to unlearn the language and sensibility of valuing the sanctity of individuals qua humanity. But it is not impossible. The history of the twentieth century is replete with examples of what Elias called ‘decivilization’.

We don’t have a time machine, and if we had one, we would struggle to engage historical malefactors in a meaningful conversation – any more than a Palaeolithic mammoth hunter could chat about animal rights with a dreadlocked animal liberationist. Every agrarian civilisation in history had relied on slavery/compelled labour. Only in the 19th century did a combination of new ideas (all stemming from the Pauline, Christian idea of the sanctity of the individual) and new technology (fossil fuelled engines), make it possible for social complexity and technological progressivism to be achieved without the horrors of compelled labour. Even so, as Marx pointed out, the emerging system had yet to provide any meaningful response to the problem of ‘wage slavery’ – but that is another story.

Until the 19th century, there was nothing remarkable or ‘wrong’ with compelled labour nor all manner of atrocities against human life and dignity. To argue otherwise is both ignorant and politically mendacious. Until the early modern period, the concept of individual human rights was not only unthought, it was literally unthinkable and inconceivable. Early Christian fathers who failed to address the classical institution of slavery were not so much hypocritical as trapped by the cognitive limitations of what was a universal experience. The fact that some were able to make the intellectual and moral leap, is testament to what revolutionary shift in cognition that Owen Barfield identifies in Pauline Christology (Mark Vernon’s book on Barfield is wonderful on this). It took nearly two thousand years for the potential of this new form of consciousness to begin to revolutionize the economy and culture of whole societies. (What really began the tectonic shift was state formation, mass literacy and growing techno- economic complexity – processes documented most usefully by Walter Ong, Ernest Gellner and Karl Polanyi, Norbert Elias)

The wonderful flexibility of English common law is precisely that it could, and still can, accommodate seismic changes in both economic imperatives and moral and cultural habits of mind, without the need for wholesale re-writing. The utopian instinct to take a new idea and apply it comprehensively and retrospectively is always attractive to the teenage mind, to gadflies and people who are semi-detached from the extant social and cultural order. But any attempt to start again at year zero/’Jahr Null’, always leads inexorably, to the gulag, to the ‘Killing Fields’, to genocidal, zero-sum ethno-political conflicts – to burning Churches full of Tutsis, concentration camps for killing Jews, gulags for Kulaks or bourgeois deviationists – take your pick. The clean break is never clean.

Any assessment of the global historical record over the last ten thousand years, must record the astonishing and unprecedented nature of what the British state did in 1833. To break with the logic of 10,000 years – all of recorded history – was a moral triumph, no matter what the Maliks and Guardianistas of this world say. It was not an achievement driven only by a moral revolution. It was pragmatic, mediated by new technological possibilities, and combined new moral certitudes with an enthusiasm for the progressive potential of the market economy.

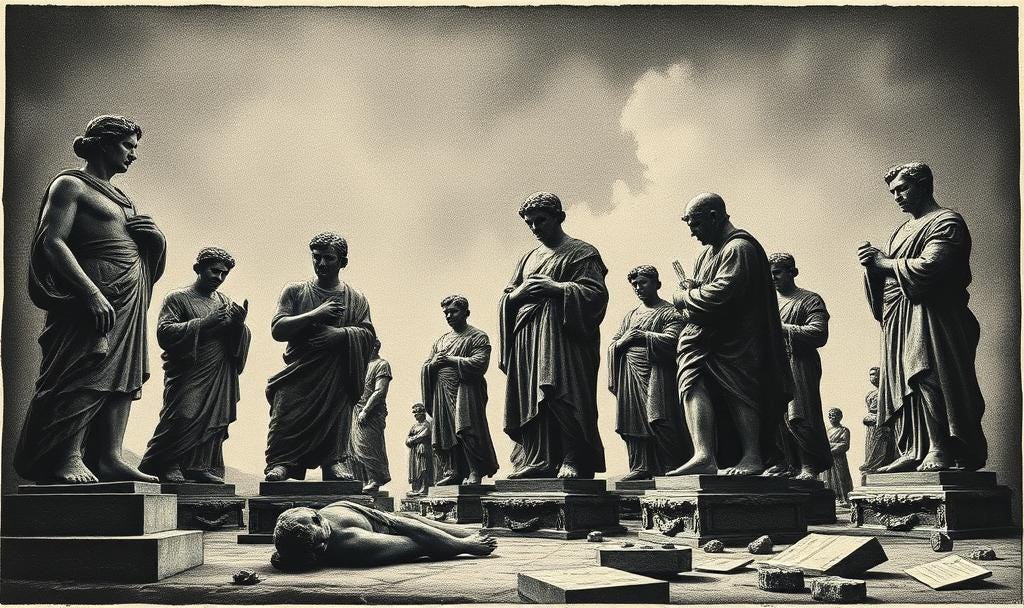

If the gradual extension of that new moral framework has progressed sufficiently that the denizens of Bristol want to take down, to move or to qualify the presentation of, statues dedicated to historical slave-traders – that is great. It is a good sign that the incremental, and iterative reformation of common law, education, and enshrined cultural predispositions, are moving steadily in a direction that most people would acknowledge is positive.

But if the mob, egged on by a woke clerisy, take it into their heads to wipe the architectural slate clean and to destroy all signs of a chequered past, without deliberation or debate, we are moving into dangerous territory – the revolutionary dream of starting again, of ‘Jahr Null’. Once the demand for brutal, unpitying consistency is backed by an armed mob, all hell breaks loose. When the ‘crooked stick’ of individual human natures, and of particular social/cultural contexts, or of nuanced historical processes, is declared broken and taboo and is abandoned with the promise of a bright, new and untarnished ‘progressive’ yardstick – things are liable to get very bloody indeed.

The slavers of 16th-19th century Europe didn’t break any laws or offend extant moral taboos – not any more than the Roman architects of the Colosseum, the Egyptian pyramid builders, the Chinese Emperors who constructed the Great Wall, the Muslim Sultans who invented plantation slavery in Arabia and used slaves in the construction of Mecca – no more, in fact, than slave owners and marketeers who provided the compelled labour for every civilisation that ever existed. The fact that their actions offend our own moral sensibilities – do I need to re-iterate at this point that slavery is a ‘bad thing’? – is testament to the complete conquest of the psychological and cultural architecture of all modern societies, by Pauline Christology: the universalist concept of the sanctified human individual as a mirror of the divine. As Tom Holland recently pointed out in Dominion – that we take the rights-laden individual as a cornerstone of any conceivably legitimate moral regime, speaks to the final triumph of Christianity. The very idea of a secular society that can articulate and legislate for comprehensive and universal moral equality and membership, without recourse to the overarching concept of a universal god, is a consequence of Christianity. And Christian or not, we can probably agree that it is a cherished and non-negotiable achievement of modernity. But if we do agree on this, we should also recognise that this achievement was only possible on the back of European medieval Christianity as the necessary foundation for: the political and moral philosophies of the Enlightenment the bloody, but in the end successful, processes of nation-state formation and democratization, and the slow emergence of a deeply-rooted liberal culture characterised by low levels of interpersonal violence – and (deep breath) – remarkably low levels of state violence (even in America). There is not the space to justify this last claim here but doubters should refer to Norbert Elias’s (2012) On the Process of Civilisation; Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature; Jeremy Rifkin’s The Empathic Civilisation.

It is historically inaccurate to describe the British Empire and its role in slavery as uniquely perfidious. It is much more truthful to recognise the extraordinary paradox that the largest empire in the world, which facilitated one of the largest and most geographically extensive slave markets in history, also created the conditions for the final abolition of slavery. This involved funding the emancipation of millions of individual slaves in such a way as to avoid economic and political upheaval, civil war and the devastating consequences of utopian perfectionism; and funding also, the Royal Navy as a means of eliminating the trade and severely limiting the ability of other states to practice slavery. And the debt incurred by the British treasury was indeed not paid off until 2015. This doesn’t invalidate other debts/critiques of Empire. But it is a fact, none the less, and should be, part of the story.

And, of course the ‘story’ is vital. Because our understanding of all of this is not simply a matter of historical record. It’s also an essential dimension of what sociologists refer to as ‘mutual identification.’ There can be no welfare state, no secure basis of legitimate taxation without a high level of mutual identification between citizens. There is a real danger that ‘critical race theorists,’ hyper- liberal identitarians, the self-righteous woke activists and useful idiots in The Guardian and the BBC, will unwittingly (at least, I hope it is unwitting) erode and eventually unravel the basis for any civic-national ‘we imaginary.’ Without the commonality of citizenship, we will revert quickly to a world of familial, clannish and trivial affiliations. It took centuries for citizenship to take precedence over tribe and clan (Weiner 2010; Gellner 1983). It was a long and bloody process. And it was only the universalization of the language of citizenship and individualism that made it possible even to think our way out of slavery. In a world of tribes, people from a neighbouring unit are, quite literally ‘non-people’ – they can be killed, raped, enslaved without compunction. The murderous duplicity of the Campbells against the McDonalds has been repeated in uncountable tribal conflicts all over the world, between Bantu tribes, warring First Nations in North America, the Mayans and Incas further south – anywhere that settled farmers or pastoralists, city states or empires, find their interests (in land, women, resources, glory) in conflict.

This was true in all complex societies, without exception. And don’t forget how, at one level, violence, rape, torture can be fun. There is ample evidence that all people – whether ‘civilised’ British, venerable Chinese, cultured Japanese, war- like Mohawks, or Chagnon’s Yanomamo – have the potential to enjoy violence and domination, just as they enjoy care, kindness and comfort (see Elias 2012 for gruesome evidence). It’s not a question of a few ‘bad Germans’. We are all ‘good Germans’ and many good Germans became bad Nazis.

The utopian ‘Jahr Nullers’ who would introduce a never-ending cycle of self- flagellating atonement, think that by ‘taking the knee’ and erasing slavery from the monumental historical record, they are wiping away the final impediments to some kind of oppression-free utopia. In fact, when such cleansing is achieved by the mob, they are in fact destroying the integrity of the ‘small-platoons’, the little civic entanglements and muddy daily pattern of living cheek-by-jowl, through which we learn to treat each other as individuals and fellow citizens. In reintroducing caste, religion and race as the primary conduits for interaction, they will make civil society ever more dysfunctional. We are already beginning to relate to each other as categories rather than as persons. With their ‘long march’ through the institutions finally coming to a denouement, the woke identitarians and post-modern intersectional race warriors are preparing the way for the destruction of the one Western legacy that counts – a world in which slavery is rightly seen as abhorrent. In the long term, post-woke politics will make slavery thinkable and the sanctity of individual humanity, once again, inconceivable. What a terrible and unnecessary tragedy!

Addendum: What do do about the statues? Generally if you want a fight, rip them down without consultation. For whatever reason, people imbue architecture and monuments with meanings and identities, and right or wrong, if activists turn the issue into a series of zero-sum confrontations, the result will be a running sore of polarization which will function as a recruiting vehicle for ethno-race-warriors and white supremacists (of whom there are currently remarkably few). Another point to bear in mind is that in a world of constant

upheaval, people find any change to cherished markers in the urban landscape, upsetting. Precious few Geordies know who Lord Grey was; most have met girlfriends or boyfriends underneath it for generations. Does that mean that all statues have to stay? Of course not. Rampaging mob is absolutely not the way to go. Statues should probably never be destroyed. Whatever feelings of emotional catharsis such acts of destruction might bring for some, would be compensated by a reservoir of resentment and latent violence on the other side.

Moving/relocating can be a useful thing to do. Even better would be to build new statues, and creative means for the meanings of existing ones to be reframed. And anything that is done must have a democratic mandate, however long it takes. Common law incrementalism is indisputably better than storming the Bastille – however much fun that is. I’m afraid, on the question of statues, look to Burke and not to Paine (who was himself nearly put to death by the the same mob that he was urging forward the year before).

Some references:

Chagnon, Napoleon A. Ya̦nomamö, the Fierce People . Second Edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977.

Davis,R. (December 2003). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 45. ISBN 978-0333719664. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

Dottridge, Mike (2005). “Types of Forced Labour and Slavery-like Abuse Occurring in Africa Today: A Preliminary Classification”. Cahiers d’Études Africaines. 45 (179/180): 689–712. doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.5619.

Elias, Norbert et al. 2012. On the Process of Civilisation. The Collected Worksof Norbert Elias Revised edition. Dublin, Ireland: University College Dublin Press.

Lovejoy, Paul E. (2012). Transformations of Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. London: Cambridge University Press.

Kwokeji, G. Ugo (2011). “Slavery in Non-Islamic West Africa, 1420–1820”. In David Eltis and Stanley Engerman (ed.). The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume II. pp. 81–110.

Pinker, Steven. (2011) The Better Angels of Our Nature : Why Violence Has Declined . New York: Viking.

Rifkin, Jeremy (2009) The Empathic Civilization : the Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis . New York: J.P. Tarcher/Penguin

Weiner, M. (2013) The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Weiner, Mark S. (2013) “The Paradox of Individualism.” The Chronicle of Higher Education 59.30