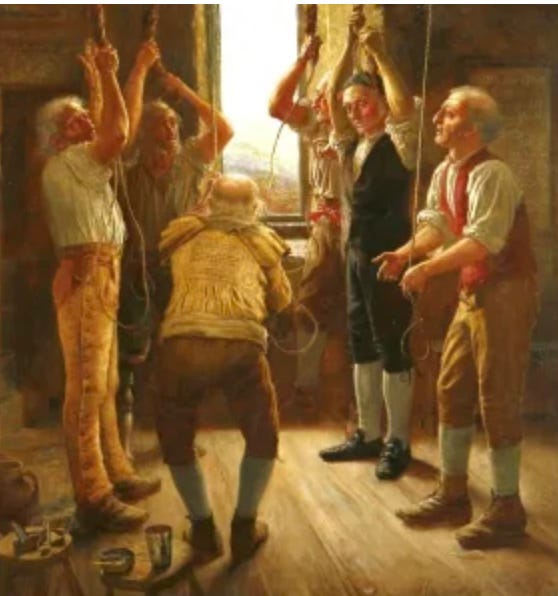

Bring back the bell ringers...

...along with the choir, candle-lit vigils and pilgrimages. To each a role and a responsibility. The Church needs to ramp up the social commitments of membership

Bell ringing (like family, or amateur sport) involves you in a sled-dog team. You have to run and participate, or be dragged along. No time even for the dog to take a piss. Like the dogs, you are pell mell pulled through the bad times and you pull others. This is what the technics of ascription achieves.

The church doesn’t demand enough from me or my family

My local Catholic Church is brand new. Although the architecture is not traditional, it is beautiful inside — full of light, maple beams, stained-glass windows recovered and repurposed from the old Church and beautifully carved stations of the cross. There is an under-used community hall that is not quite big enough to hold a barn dance — a massive fail in my opinion. And being built into the structure, the overall shape of the building is a little distorted and blobby, taking away from the classical cruciform configuration with the long knave and transept. But compared with any of the atrocities from the 1960s and 1970s, the building is a winner.

However, even if the church doesn’t fall into the aesthetic abyss of post-war modernism — it does fall prey to a kind of functionalism of the lowest common denominator. There is a massive car-park — because it’s North America. We expect to roll-in and roll-out without as much as a hug or a handshake for our fellow parishioners. The Knights of Columbus do their best with an occasional fundraising breakfast in the hall. It would be much better to have coffee and biscuits every single week. But, it would also be much better if there was something that was remotely attractive to anyone under 30, or for teenagers — table tennis, some beaten up leather sofas, a performance space. But there is none of that. Naturalizing the modernist way of the world — the Brownian motion of billiard ball individuals — we build our Churches and structure our institutions to match. Families roll up — as they would to a Tim Hortons drive through — make their peace with God, take communion and then roll out.

Among the senior citizens, there is a residual structure of care and mutual regard — from a generation that was less mobile and whose affective regard for each other was more coloured by the place-bound loyalties that come with simply staying put. As that world disappears into the rear view mirror, it becomes very hard for the clergy to make any dent on the liquid, impersonal and unloving nature of modernity. There is no sense in which all the kids in parish recognize each other from church, or socialize with each other. There is no active Catholic youth club. There are no barn dances, and zero opportunity for Catholic teens to date and court. In fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine where the next generation of Catholics is going to come from — and it’s difficult not to reflect that perhaps the lack of experience of most priests in this department is not helping.

On the other hand, the Catholic church has been around for 2000 years. It has shown a generational sticking power that is matched by almost no other institutions — the British and Chinese states perhaps. So in the DNA of the Church there must be the institutional and cultural knowledge of what is required. Although relevant, I’m not going to get into all the debates about Vatican II, the Latin Mass and modernity versus tradition. I just want to make a sociological observation that links the crisis of declining church attendance, piety and cultural traction with the more general crisis of Western/modern culture. It turns out that the culture of sexual promiscuity and individual gratification — narcissism on steroid — also can’t sustain itself over the long haul. Modernity is one great big demographic non sequitur. It is literally killing itself — with drugs, depression, loneliness, joyless sex, material wealth and a complete absence of any meaning.

Fierce communitarianism sounds good to me

Here on Substack, postliberal

just made a vigorous case for fierce communitarianism. I love this essay and think everyone should read it. Summarizing statistics relating to loneliness, depression, social mobility and the variety of trends undermining the ‘stickiness’ modern society, Pete makes the case for a pronounced ‘social recession’.There are a number of trends that can be knitted together under the heading of a ‘social recession,’ or a ‘loneliness epidemic,’ which features more people spending longer periods on their own instead of engaging with others in social settings face to face.

Drawing on Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone and the classical sociology of Emile Durkheim, Pete makes more pithily the same case that I have made frequently myself, here:

And here

In particular, Pete underlines the link between the manner in which technological modernism allows us to satisfy the hierarchy of basic needs without recourse to close-knit relationships. ‘Rugged survivalism’ where success depended on recurring and steadfast interactions and nested group loyalties (family, kin, tribe, community, nation) has given way to ‘modern atomization’… “precisely because we no longer have rely upon the protection of such close-knit communities in order to survive.”

Pete is completely correct in seeing what he calls the ‘social recession’ as an intrinsic feature of modernity. For tens of thousands of years before the modern revolution, all human societies were ‘fiercely communitarian’ — to such an extent that loneliness doesn’t exist as an experience or even a concept. This is an aspect of what Owen Barfield referred to as the ‘participating consciousness’ — a concept around which I have circled in many previous posts. For Pete, the loneliness epidemic — and also, I would add, the culture of narcissism that preoccupied Christopher Lasch, Jean Twenge and Phillip Rieff — is a necessary epiphenomenon of what Joseph Henrich referred to as WEIRDness i.e. Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic societies. Integrating mountains of comparative data, Henrich suggests that Western societies are unique in the extent to which people focus reductively on personal attributes and intentions rather than, as with Asian societies, think holistically about relationships and intentions. Where as people outside the West focus on kinship affiliations and loyalties, WEIRD people — the atomized individuals of archetypically modern societies — are more trusting of strangers, more likely to give blood, and more likely to have faith in public citizen-based institutions that makes such trust possible. The same features of Western society make it easier for individuals to identify as members of voluntary associations — based on all manner of political, leisure, religious, hobby or special interest groups — rather than extended clans. It is this dense matrix of associations and cross-cutting affiliations that made possible guilds, charter towns, universities, competing religious orders and eventually impersonal markets, the growth of cities and nation states.

Henrich’s thesis brings me back to the role of the church. Christianity, he argues, paved the way for modern institutions. This was much more than the Weberian argument about protestant individualism; or the bloody wars and hard-fought Westphalian peace that entrenched a new conception of the rule of law; or the suite of social contract theories that provided a philosophical anthropology for the new proto-democratic regimes. Preceding these early-modern convulsions, the Christian institution of normative marriage and family — ideas which go right back to the Gospels and the letters of Saint Paul — provided both a rationale and a means to circumscribe clannishness, dampening the absolute pull of kin-based loyalties. The resulting release of pressure allowed the emergence of more rule-based, impersonal and individualistic institutions mediating between the nascent citizenry and the emerging nation-state. Bailey and Clark refer to the explosions of clubs and societies in British culture in particular as the emergence of a new ‘associational world.’1 For Henrich, the Protestant Reformation simply elaborated to a logical conclusion what Catholic Church had set in motion 1500 years before.

Aside: the next step of the argument contains a kind of irony. In the story, thus far, Christendom, especially in England, facilitated a transition from clannish, tightly-knit kin-society to a Christian civil-society of charities, guilds, mutual aid organizations, leisure and special interests associations and hobby clubs. What happens next is that without the glue of religion, family and place-based attachments — this dense mediating texture of civil society associations proved ephemeral, fading like pond ice in the April sun. This has happened even as the Internet has allowed a cultural big bang in the proliferation of online associations in relation to an astonishing array of special interests. But in the absence of a place-bound, face-to-face community, digital association has done nothing to arrest the decline of sociality. However, more of that later.

Reflecting on the same process, Norbert Elias (see here) showed how iterating expansion of both the state and impersonal markets operating over wider areas and intruding into more functional domains, led to the emergence of a more constrained psychological habitus and the internalization of more stringent and differentiated controls on individual behaviour.

Observing the steady decline, over a period of a thousand years, in levels of interpersonal violence within Western societies, Elias conducted a detailed study in the plasticity of the human personality. His account of ‘civilizing processes’ links the external constraints associated with the formation of effective and centralized nation states, the growing complexity of transactional market relations and structures of extended interdependency between relative strangers — people who may not ever come into personal contact. The internalization of external constraints through systematic and directional processes of socialization created an overwhelming psychic habitus that was completely different from any previous society. Elias was clear that advanced complex societies were unprecedented in the degree of such internalized restraint. But the mechanism — the jockeying link between what he later called the ‘triad of controls’ was as old as humanity. The controls in question — controls over nature, social controls over others and internal psychological controls — operate in all human cultures, qua humanity.

It was this process that produced the ‘weird’, contained, ‘Cartesian’ personalities who were able to place their faith in abstract rules. But critical to

’s thesis, one aspect of this ‘great transformation’, was a shift from face-to-face interactions to patterns of constraint consequent upon faceless interdependency — as I related in more detail here:And the less that face-to-face interaction and enduring personal ties and relationships are necessary to make a living and to survive, the more individuals can approximate to the insane, utopian anthropology of isolated, contract making, transacting, sovereign individuals that formed the modern world. The more that the world is inhabited by the weird kind of people imagined by Descartes, Hobbes, Rousseau, Smith and Kant.

Alasdair Macintyre is not alone in explaining the same shift less in terms of socio-economic processes, and more in terms of the metaphysical revolution associated with nominalism (see Alin Vara’s review of Gillespie’s The Theological Origins of Modernity). Abandoning the Aristotelian virtue ethics that had dominated Medieval theology for centuries resulted, he argued, in the cacophony of incompatible moral and epistemological visions that define modernity. Nominalism relativizes previously shared and objective moral standards reducing moral philosophy to an unproductive and irresolvable "clash of antagonistic wills." Clearly both ideas and techno-economic development — ideological change in relation to metaphysics and also the Great Transformation economy and society (Elias, Polanyi, Marx, Weber, Tonnies) —operated in tandem. Either way, the image of contained, independent individuals has supplanted the more realistic self-image of human beings as Dependent Rational Animals (the title of Macintyre’s sequel to After Virtue) — with pathological and unsustainable consequences.

Anyway, as I have argued in the posts linked above, this modern individualism is a potential opened up by the Jewish and Christian Imago Dei. As Owen Barfield discerned, we can only engage with the monotheistic God — I AM who I AM — through a process of psychic withdrawal and containment and the emergence of a non-participating individual. Thus the political-economic genesis of the modern individual charted in different but complementary ways by Max Weber, Charles Taylor, Karl Polanyi, Norbert Elias and others, was simply the simply the unfolding of the potential of that question originally put by Moses to God in the burning bush. Teh question “Who are YOU?” was simultaneously opening up the problem of ‘Who am I"?” or indeed ‘Who is anyone?’ However, in a Christian (and Jewish) context the destructive fragmenting potential of this historical individuation was always contained and restrained by a understanding of freedom that was fundamentally self-sacrificial. Ultimately, the sovereignty of the individual for orthodox Christians was to become a slave to God — just as a mother or a father learns the meaning of self-realization by self-sacrificial love of spouse and child.

It is then not difficult to understand what happens when the sociological drivers of individualism not only accelerate and intensify, but in an unprecedented context of secularism, materialism and unbelief. Harnessing unlimited energy reserves and the power of scientific modelling and technological manipulation of the natural world, modernization has delivered an almost exponential expansion in the social division of labour — and a corresponding complexity of roles, cultural artefacts, significations, languages, memes, and patterns of individual experience, all of which provide building blocks for a proliferating kaleidoscope of individual identities — of ‘I AMs.’

In many ways, these individual identities and personalities are constructed out of the crucible of constraint — sensu the progressive civilization and internalization of constraints of Norbert Elias. But in another metaphysical sense, the accompanying materialism and naturalism has also led to the relativization of all moral frameworks and undermined any ontological basis for self-subjugation and self-sacrifice.

And this is now the world in which we live. Following Alasdair Macintyre, we have lost the shared moral framework that once held all of Christendom in its tractor beam. There is now no established matrix of shared virtues — agreed upon by parents, schools, clergy, social workers, policemen, officers of the court, jurists, politicians, journalists — which we can rely upon to guide the socialization, education and occasional correction of our children. Liberals are often fond of repeating the apocryphal aphorism that ‘it takes a village to educate a child’ (Hilary Clinton actually wrote the book) They like it I think because it is ascribed to ACME ‘traditional’ culture and blurs the communitarian versus collectivist nature of the ‘we’ involved. To the extent that there is a communitarian ‘we’ it is conveniently part of morally superior non-Western culture (usually African) — so you can forget the obvious point that the African cultures advancing this idea are predicated on kind of Ubuntu virtue-ethics that is far closer to Thomas Aquinas than to the global liberalism of Hilary Clinton. But to the extent that such an idea becomes the basis for thinking about policy, there is a bait and switch: the ‘communitarian we’ with its ancestral and common sensical resonance is replaced with a ‘collectivist we,’ instantiated by this or that organ of the state apparatus. The sister, aunt, neighbour or family friend is replaced by teacher, social worker, council worker.

The collectivist apparatus — made possible by fiscal redistribution and extensive mutually reinforcing monopolies of policing, violence, law, utility service provision, health and welfare — is facilitated by the more general shift away from iterative, personal, face to face interactions in modern life. As indicated in the discussion above, modernity is predicated on inverting the relationship between a tiny number of ‘strangers-who-stay’ (after John Berger, discussed here) on the one hand, and the immersive placental fluid of life-long friends and relations on the other.

The transactional exchange with any collectivist functionary is no different to the billiard-ball inflection we experience with any one of the thousands of abstract non-person ‘role-bods’ with whom we are interdependent but don’t interact as rounded people.

Hence, the same liberals who emphasis the role of the ‘the village’ are quick to deny any actual virtue-ethical community — for instance, American Catholics — a role in adoption, if they are not willing to subordinate their moral priors to the version of universalist emancipation promulgated by the state.

The paper-thin and increasingly legalistic frameworks which guide both policy and behaviour are a function of this loss of a deep, pre-cognitive and shared moral framework. Prior to modernity, the inculcation of such a framework was driven by shared patterns of socialization rooted in pervasive and unquestioned institutions of family, church, community-self regulation and guild — and it was sufficiently extensive as to become naturalized and appear intuitive. Modernity has both elaborated and differentiated such perceptually naturalized forms of internalized psychological restraint particularly in relation to interpersonal violence (as evidenced by Norbert Elias and more recently Steven Pinker). But paradoxically, it has also simultaneously destroyed the shared moral basis of such behavioural restraints, and the shared communitarian basis for mutual identification. Elias understood significance of the declining salience of the communitarian ‘we’ about which he wrote extensively in The Society of Individuals. But he was overly optimistic about capacity of individualized psychic controls to compensate.

Loneliness is precursor to instability

In his essay,

summarizes rather starkly the crisis of loneliness and anomie. The data relating to divorce, one parent families, single child families, solitary leisure pursuits, the recession in sexual activity (as the surprising concomitant of the sexual revolution), the declining per capita number of friendships (especially for men), the pervasive use of pornography and other fake-forms of Internet sociality — well frankly it’s all rather depressing. And of course, ultimately, it means that society is quite literally dying. We are failing to have children, and failing to socialize effectively those that we have. Many societies are experiencing headlong demographic collapse.We should be worried about this for all sorts of reasons. Without young people, it will be difficult to sustain economic growth or to generate the economic and labour resources to look after a rapidly aging population. Western societies attempting to fill the gap with immigration are creating a potential for cataclysmic inter-communal violence. And if our response is to rely on automated A.I. controlled technology, there is a very real danger that humanity might give way altogether to some kind of transhumanist post-human hell (I say ‘hell’because as a Catholic I really do believe that we are created in the image of God. Replacing God’s creation with a human artefact seems prima facie diabolical).

Christianity and Fierce Communitarianism

Anyway, none of this is good. Which brings me back to my own communitarian life-boat, the Catholic Church — and by extension all Christian churches. What Christianity gave to the world, was a path out of tribal sectarianism — and the capacity to treat all human beings as equal under God. Jesus parable of the Good Samaritan or St Paul’s riff on ‘neither Greek nor Jew’ evoke what is now a commonplace morality. But as Tom Holland has shown, the cosmopolitan world of human rights and international law which percolated through and out of Western Christendom over a period of 2000 years, is thoroughly and completely Christian — even in its most crazy Marxist or progressive inflections, and paradoxically, even in the concept of secularism, atheism, the privatization of religious experience, and the separation of religion and state. Cue the Monty Python meme.

However, with atheism, secularism and the kind of privatization described by Charles Taylor, something has broken. The cosmopolitan, internationalist promise of Christ that made the idea of world peace — as a function of generalized love rather than the imperial imposition of Pax Romana, Pax Britannica or Pax Americana — even thinkable, depended ultimately on a personal relationship with God, and upon personal relationships with other people. Christian freedom always involved a vision of liberation through self-constraint. Without God, such freedom becomes self-referential, corrosive and destructive.

The idea that individual freedom is only truly realized through relationships with other people, with family, neighbours and relative strangers, and with God — clearly opens up all those interminable debates de jour about the meaning and parameters of Ordo Amoris. There is no escaping the politics of this, however much Christians on all sides try. Christians who are variously socialist, progressive, conservative and or green in their engagement with the world can’t help but argue over the interpretation of scripture, theology and sacred tradition. I have made some observations about the Christian engagements and obligations with respect to immigration, here:

And here

However I do want to make one further observation. There is balance in the nested imperatives of Christian love, between face-to-face, personal, ongoing relationship obligations to specific people on the one hand and abstract obligations to humanity as a whole on other — to people who are individuals but whom we know only as numbers, or as iterations of an abstract category. In Jesus’ parable, the Samaritan responded to the needs of a stranger. He crossed the clannish boundaries of ethnicity and family. But — and it is a massive but — this was still a person-to-person, face-to-face expression of love. He was not responding to the abstract personhood in the sense of ‘the starving child in Africa’ or the ‘unknown soldier’ or even simply ‘the poor’. This was a particular man, with a face, who was in trouble. And this is not to say that Christians don’t have obligations that are mediated via such abstractions. We do. But there are trade-offs in the Ordo Amoris we move from personal interaction to impersonal and abstract interdependency.

In attempting to take God out of the vision of Christian love, liberal humanism has always moved towards abstract and impersonal love — invariably with the best of intentions. This was evident in the French Revolution and every episode of utopian construction ever since. Unfortunately, abstract humanism without inter-personal love has always led to a situation in which an instrumental rationality takes over and the ends justify the means. Again and again, the hubristic optimism of secular humanism has led to the massacre of millions — collateral damage in a world in which, as Stalin observed, one death is a tragedy but a million just a statistic.

And yet as

observes, with unprecedented wealth, limitless energy per capita (at least by any historical comparison) and technological sophistication that is practically magical, we are building a world where we don’t need each other. At least we don’t need each other as particular intimates — as people as faces with whom we interact, individuals with needs which we are able to address, with specific interests or personalities that may clash with our own. All of those basic needs identified in Maslow’s hierarchy — sex, food, warmth, clothes, money — can often be met simply by clicking on a computer or talking to the disembodied fake-voice of Siri or Alexa. And the more we normalize this world of impersonal transactions, the more we are drawn into the abstract logic of collectivist solutions in which state bureaucracies attend to the needs of faceless recipients of impersonal care. The logic of this world is unfailingly loveless. As we fail to have children, as people fail to marry, as marriages fall apart and families become more dysfunctional — the state will take over, with trans-humanist technologies that literally write human interaction out of the script. In this way, collectivism, abstract impersonalism and transhumanism go together.Ringing the changes

Which brings me back to Christianity as we do it — to Orthopraxis. The most important thing that churches can do is radically to increase the demands that parishes make on individuals to participate — in the liturgical year of course, but also in the life of the Parish and the lives of each other. The very first order of business for a parish priest should be to put bums on seats. This means a long term plan for creating marriages and babies, for integrating grandparents and cousins and neighbours into extended solidaristic families. From this perspective, just as much as ensuring that people fast for Lent or attend Sunday Mass, the Church needs a plan to ensure that parishioners provide community for each other, that more than secular school friends, children are present at each other’s birthday parties, that feast days engender family get togethers and BBQs, and that there is a sufficient critical mass of teenagers such that Christian organized dances become the main arena for courting.

Attendance at Mass should involve a rich and ongoing set of personal interactions and the development of relationships — yes of care and mutual support, but also joy and friendships unfolding over life-times, and across generations. This is important because in our privatized, car-dependent and busy lifestyles, for many people a church service often takes on the quality of a abstract transaction — a checkbox to be ticked each week, or perhaps just a couple of times a year.

This is not to say that there are not opportunities to become more deeply involved. For example the two churches that I attend have fantastic choirs and music directors. The Knights of Columbus do a great job and organize occasional breakfasts. The Catholic Women’s League are also active. But nevertheless most parishioners (and I include myself) manage to avoid the ascriptive tug of church service. Whereas in a medieval village, the Church was the entertainment, the leisure pursuit, the public carnival, the procession and the spectacle — now it competes with Netflix, the kids’ hockey schedule and all the rest. And the organizations that do exist involve almost exclusively older people — many in their 70s and 80s.

I don’t have any good ideas about how to change this. However, it does occur to me that across the liturgical year there are many opportunities for participation and engagement. Almost every week. Perhaps, as a matter of urgency, the clergy should think hard about shifting the structure of feeling, the norms and even the explicit rules that govern our Orthopraxy — what we actually do together in our religious life, as opposed to what we should do — in the direction of ascription, gentle persuasion and even compulsion, rather than choice and bland opportunity.

And finally — bells. There is nothing more evocative in England at least than the sound of Church bells. My mum grew up as a bell puller at the ‘Boston Stump’ (St Botolph’s) in Lincolnshire.

Bells and bell ringing have been a staple of literature for ever. In Goethe’s Faust, it is the sound of the bells that brings the Doctor out of his isolation and reverie and back into the world. Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Nine Tailors, centres on bell ringers and the tolling of the ‘Tailor Paul’ bell nine times to signify a death. There are dozens of examples. The English tradition of ‘ringing the changes’ was made possible by the operation of each tuned bell by an individual puller — allowing complex combinations of notes and scales (as opposed to the automated carillon of the continental tradition which can be played by a single person). But it is not clear how long this thousand year tradition will continue to resonate through the culture because bell-ringing may disappear. Like the Church choir, bell pulling requires a reasonably large number of individuals to train together and commit to being available for an inflexible daily and weekly schedule — the kind of schedule and commitment that really indicates that one is putting God first, by servicing your own community.

Just as owning a dog, is a good way of making sure that an otherwise unwilling body will get up and walk even in the most inclement weather, the commitments to take responsibility for an aspect of communal life — whether it is a football club, a choir or the church bells — means stepping into the stream of mutual obligation and daily/weekly personal interaction and friendship.

My own sense is that if the Church is to survive and our society to thrive — and particularly if we are to start seeing strong marriages and growing parishes with lots of children — then we need to find ways to make materialism and individualism take a back seat. With respect to bells, I should add the obvious caveat. In England, most Catholic Churches don’t ring the changes with the sophistication of the Anglican bell-ringing tradition. Seventeenth century innovations in bell ringing occurred in the Anglican church and there are still some legal restrictions on Catholic Churches. Nevertheless across Anglican, Catholic and Lutheran traditions the primary purpose of ringing church bells is still to signify an imminent liturgical service. Many also ring their external bells three times a day (at 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m.), summoning the faithful to recite the Lord's Prayer and within the Roman Catholic Church to pray the Angelus. And the association of the Christian tradition will bells goes back nearly 1600 years, being introduced iby St. Paulinus of Nola in 400CE and sanctioned for wider use by Pope Sabinian in 604CE. Since then all sorts of associations have glossed their use — from the driving out of demons to signalling moments of local or national peril or triumph. Within Catholicism the ‘Ritual of the Baptism of Bells’ involves the washing with holy water and anointing of bells by the Bishop.

However, with a view to the problem under consideration here, the most significant aspect of bell ringing is what Lewis Mumford would call the ‘technics’ of the practice. Like the choir, bell ringing requires practice, training and year-round commitment. It provides another way to rope (young) people into a simultaneous and ascriptive training of body and mind which also creates relationships — regular horizontal affective and cooperative bonds between parishioners. Bell ringing like any other ‘hobby’ creates social glue.

This matters. The Church needs to prioritize the parish as an ascriptive environment in which it is harder to avoid community participation and engagement than it is to simply say yes. The bishop, the priests and the deacons, the heads of Catholic schools (and this goes for other Christian churches also ) need to be licensed to ask — or rather to demand — much more of us.

Just as an experiment, we should start by insisting that all new Churches are equipped and many older ones retrofitted with old-fashioned, person-operated bells — that these are dedicated and made meaningful to the community. With bells in place it then becomes a matter of shared pride and personal obligation that these are operated and that ringing the changes becomes a regular and cherished feature of the audio-landscape of the community — so much so that the sense of place is once again made indivisible from the sounds of Christian worship. By the same token, Bishops should be innovative using public festivals and competitions as well as funding musical directors to promote parish choirs. And finally the same approach should be adopted in relation to youth clubs and teen dances. As a matter of urgency, Bishops should get parish priests to make an ascriptive Catholic youth culture involving parents and creating appropriate opportunities for fellowship but also just courting and having fun. No fun, no marriages, no children and no church. It really is as simple as that.

Bailey, Peter & Clark, Peter. (2001). British Clubs and Societies, 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World. The Journal of American History. 88. 1054. 10.2307/2700417.

![My sheep got her head stuck in a Guinness box...[on John Berger's 'stranger who stays']](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Bh0S!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F52f0ca6f-e6b8-4682-849c-df3ec1d9bdf1_802x430.heic)

Again, very thoughtful. Thank you for mentioning my piece. This is a very good accompaniment to it.