To Form or to be formed: Iconic Bridges and Idolatrous Culture-de-Sacs

On the Christian cultural 'war of position'

How should Catholics and other Christian denominations should go about re-Christianizing the West? Struggling against the hegemony of the Catholic Church, Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci conceived of what became the ‘long march through the institutions’ —the so called ‘war of position’ i.e. the struggle to frame ordinary, commonsensical understandings of the world. This cultural battle was, for the Party, to be a preliminary to any overt move against the State, or ‘war of movement’. Christian common sense is still the foundation of Western civilization — but it is fragile and retreating. In what follows, I start with a little ancient theological history and move into some big picture accounts of what modernity has done. The essay finishes with a sort of manifesto — things I wish I could put in front the Bishops and Cardinals who might be able to get things moving. There are some good ideas and some silly ones. I don’t know any Bishops, so I’m just putting them out here. Enjoy. God bless

Forming the culture: wide or deep?

Catholic — from the Greek Kata-holos — means something like ‘according to the whole’.1 The Church has spilt a lot of ink (and sadly a lot of blood) trying to navigate what that means. The creed commits us to ‘one Catholic and apostolic faith’ — a forward moving, evangelizing, inclusive and universal imperative directed at everyone qua humanity. The difficulty lies in the nature of the semi-permeable membrane that separates this particular entity (the body of Jesus) from everything around it.

Too little differentiation, and things fall apart; the movement loses coherence and momentum. Too much — and the door opens to Freud’s ‘narcissism of small differences’; or the human universal that Monty Python lampooned with the ‘People’s Front of Judea’ sketch in the Life of Brian.

And yet it is so hard to know where to draw lines. Who’d really want to be the Pope? Saint Augustine’s conflict with the hard-core North African ‘Donatists’ was reputedly the original source of the ‘catholic’ moniker. Berber Bishop Donatus had favoured a punitive, disciplined and rigorous priestly caste that could draw a clear line between the commitments of a truly Christian life, and the visceral and earthly orientation of the fallen world around them. This meant a policy of zero tolerance or forgiveness for more pragmatic colleagues who bent the knee during periods of imperial repression. For Augustine, this purist vision made narrowness a virtue. Not only did it undermine the mission of wider evangelization outside North Africa, but the zealous, implicitly competitive and unforgiving approach to holiness underplayed the necessity of God’s grace — a gift that was available to all, through Baptism.2 In one sense Augustine was re-litigating the fight he had already won against the followers of Pelagius who also, too greatly, emphasized the boot-strapping capacity of virtuous individuals to raise themselves through good works. Taking Augustine’s side, the ‘catholics’ prioritized the spread of the Church throughout the known world. They recognized that an unachievable high bar for the priestly vocation would make such wider evangelization difficult. A refusal to countenance any pragmatism in dealing with secular authority would make it impossible.

The use of the term in the creed underlines the universal mission of the Church. This was first evident in the debate within the Jewish Jesus cult as to whether to admit gentiles and if so, whether they should conform to traditional Jewish ritual practices, such as circumcision. Paul’s definitive insistence on universalism was reprised a 1000 years later when the Gregorian reforms sought to preserve the Church’s authority over the increasingly strong secular authorities. Specifically, Pope Gregory sought to push back against corrupting forms of clerical-state collusion in relation to practices such as kingly investiture (the state chooses the local cleric), simony (trading church positions and sinecures) and priest marriage. Once again, the significance of the Gregory’s tussle with secular power was the preservation of a church that, at least in principle, stood aside and over the particularity of political power. Catholicity in this sense was the insistence that Christianity reached into every domain of human life and would not be restricted to fulfilling an adjunct spiritual function for the state. A 1000 years later, at the end of the 19th century, Vatican I was fighting a similar battle to maintain the Church’s role in the the whole life of both individuals, but also communities and nation-states — and resisting the modernist pressure that would restrict religion to a private therapeutic role for individuals, private faith without public reason.

Although, the magisterium has maintained this position, mass society has flowed around the Rock and as Charles Taylor has described, a defining feature of our ‘secular age’ has become the privatization of faith — a choice that individuals can opt into on their own dime, in their own time, as long as they don’t upset the rhythm of the wider community.

In other words, the forming mission of Christianity has become, itself, formed by secular culture — pretty much exactly the problem that defined the history of Jewish culture after Exodus, turning away from God and being pulled back by a cycle of humiliating defeats and succession of long suffering prophets.

Take Away

So there has always tension between the imperative of universalism and maintaining the correct course; the need to engage widely, without being diverted or corrupted. Christianity has always been the first and only true form of internationalism — and all modern liberal incarnations (Human Rights, the United Nations, International Law) are secular derivations (as

has demonstrated — beyond all doubt, I would add). But from the moment that Saint Paul first signalled the embrace of the gentiles, the expanding Church has had to find ways of accommodating and integrating diverse cultures, habits of mind, group-histories, economic systems and political conflicts. The impetus to purity and the playing out of these tensions /compromises has led to a pattern of schism with which we are all familiar — Eastern versus Western Empire, Greek and Latin, Lutheran Reformation, the Protestant fragmentation; and currently within the Anglican fold, African and Asian orthodoxy versus Anglophone modernism.Ritual versus sincerity

For protestants of all denominations, ecumenism presents both strategic and theological problems, but it is not existential. Leaning heavily on individual revelation and scripture, and generally wary of ritualized tradition and institutional authority, protestantism has tended to privilege 'authenticity and an uncompromising understanding of the truth, over ecclesial unity. So the protestant project really doesn’t depend on ecumenism. Whereas, for the Church of Rome, it’s in the name. The moniker ‘Catholic’ highlights a self-understanding predicated upon a theological and institutional capacity to sustain a broad church — a church which aspires to include all Christians, qua followers of Jesus. Every schism hurts!

The habitual protestant preoccupation with authenticity is noteworthy and has been examined closely by Adam Seligman (here and here). He contrasts two modes of engagement with the world: ‘sincerity’ versus ‘ritual’. Ritual —operating like play (as with Huizinga), humour and myth — generates a predisposition to live with ‘suspended disbelief’ and multiple, potentially incompatible realities. This is clearly the way that most humour works — the quirky, unexpected juxtaposition of different worlds. Narnia might be, is (possibly for the purposes of this game) just past the coats in the wardrobe. This is the subjunctive modality of ‘as if’. In contrast, the modality of sincerity tends towards zero sum assessments of truth/falsity. Seligman likens this cognitive frame to the stereotypical teenager’s ‘it’s either true or false, right or wrong and there can be no confusion’ [and I should add: ‘Dad — you’re a complete (inauthentic) hypocrite’]. This propensity for a literal either/or-ness is akin to certain expressions of autism. It is also the modality that has, he argues, completely dominated Western science, culture and institutions since the 16th century.

Like play and humour — ritual creates subjunctive "as if" worlds that are rooted in human imagination. The capacity to traverse imagined worlds and inhabit a different cognitive/subjective universe is central to the human capacity for empathy. Sincerity, on the other hand, foregrounds the search for explicit truth and encompassing unity — complete models and an absence of doubt . This modality tends to construe fragmentation and incoherence as indicative of inauthenticity that must be overcome. The overlap between protestantism and the rise of modern science is partly a function of this commitment to singular shared models and explanations; and the rationalist assumption that with enough debate and explication, agreement will be forthcoming. This is the underlying operating premise of the Quaker approach to mediation and conflict management.3 The ritual imaginary of Catholic and Jewish approaches tends rather to an acceptance and permanent balancing of different ‘as if’ models of the world and the inevitability of subjunctive pluralism.

In many ways, Seligman’s account of modernity as a sharp oscillation towards the pole of sincerity is highly consonant with Iain McGilchrist’s hypothesis that Western civilization has moved towards a kind of pathological left-brain dominance. Left brain function is typically associated with a mode of attention that is grasping, explicit, analytical and oriented towards either/or binaries; the right hemisphere is exploratory, implicit, provisional, encompassing, aesthetic, engendering a diffuse, multi-modal form of attention to the world. Civilizations — Greek, Roman, and now Western — tend to move unconsciously inexorably from a balanced relation between the Master (right) and his Emissary (left), towards the domination of the latter. W.N. Whitehead said that civilizations reach the zenith prior to a fall when they start to analyze themselves.

“I should think it likely. The prime of Athens came a little before Plato, in the period of the three great tragic dramatists — yes, and I include Aristophanes’ comedies too. I think a culture is in its finest flower before it begins to analyze itself; and the Periclean Age and the dramatists were spontaneous, unselfconscious.” Quoted in Lucian Price ‘The Permanence of Change: Dialogues of Whitehead’ The Atlantic, April 1954,

McGilchrist has argued that protestantism — and the whole cycle of iconoclastic revolutions described by

in Dominion — was associated with a period of left-brain excess. With it’s propensity for abstract theological formulation and explicit positions; its suspicion of symbolism, iconography, metaphor, implicit meaning and ritual — protestantism shares more than an elective affinity with excessive rationalism of the Enlightenment and the violent iconoclasm of the French Revolution (and those that followed).On a personal note, this aspect of Seligman’s argument rings very true. Growing up in a Quaker household, the link between Quakerism and autism and/or an intense version of the sincerity modality, doesn’t seem at all implausible. George Fox’s abiding claim was for authenticity and truth (‘my word is my bond’). My parents acted as Quaker mediators during peace process in Northern Ireland. As they were leaving after a decade and I was taking up a position in Dublin, I clearly remember my mum telling me that I was about to realize ‘how protestant I was’. Culturally she had found her approach to meetings, minute taking, and argument was very similar to that of the unionists (also protestant) in focusing on right/wrong, yes/no questions of good faith and veracity, and the pinpointing of individual responsibility in relation to agreed actions. Their protagonists on the Catholic (nationalist) side, she observed, were more inclined to assume a degree of conceptual slippage and translation problems consequent on different ways of being. The ritual approach to conflict, observes Seligman, is more able to evoke into being a temporary shared ‘as if’ space of empathy and co-belonging — even if only for the period of the game. Truth or falsity is beside the point. For our shared purpose here and now, we will act ‘as if’. He once observed wryly that, for two antagonists who could never, ever agree intellectually or rationally — e.g. a queer, non-binary/ or lesbian female Anglican seminarian and aspiring priest and a dyed in the wool, Ugandan Anglican bishop (or perhaps a pair of IRA and a Loyalist terrorists) — simply sitting down once a week and sharing a cup of tea (a ritual) could be a win, and could…perhaps…down the line, lead to something else. The important thing was to keep drinking tea and not try to find some rational basis of agreement (other than ‘it’s a nice up of tea’).

Ritual allows the balancing or juggling of different cognitive or ontological realities without resolving down to a single truth. In some circumstances there is an element of ‘fake it until you make it’. Talking to Justin Brierley about her tentative tip-toeing into Christianity,

used exactly this phrase, suggesting that going through the ritualized motions might lead to a firmer inner transformation (faith). This would be a case of the body leading the mind; or in McGilchrist’s terms, an immersive, aesthetic, multi-sense, and holistic right brain mode of attention (all the bells and whistles) allowing the reining in and tempering of the analytical, grasping, ‘know-it-all’ skepticism of the left.Quakers don’t do ritual. Their approach to faith is very cognitivist and sincere. This is why they don’t do the sacrament of baptism — believing that only independent, sovereign rational adults are able to make the necessary commitment and transition to become members of the Society of Friends, without the necessity for ritual (‘my word is my bond’). Many never make the transition and remain lifelong ‘attenders’. Nothing could be further from the Catholic approach to baptism, catechesis and strenuous psychological, theological and cultural ‘formation’. Over 2000 years, the importance attached by the Orthodox and Catholic Churches to creating a culture — the rising Christian tide that floats all boats — has raised the ‘fake it until you make it’ school of religious training, to a civilizational art form. But what happens if that tide retreats — as in Mathew Arnold’s poem. On the one hand, it might be the case that the future of Christianity rests with small groups of charismatic evangelicals harking back to the Apostolic age. This could suggest a swing even further towards the modality of sincerity — a rigorous emphasis on public piety, truth telling and a rejection of compromise.

But equally, traditionalists could argue that Western disenchantment is the logical terminus of Reformation. The rejection of traditional authority in favour of scripture and revelation engendered a charismatic effervescence that quickly rolled over into the liberal Enlightenment and forms of secular individualism and relativism that abandoned faith altogether. The path to recovery, they argue, involves the remembrance of tradition, including all the ritualized bells and whistles, and the creation of place-bound, cohesive communities with a heavy steer towards solid marriages, large families and very public and ritualized catechesis and formation. This approach certainly seems to be gaining ground in North America.

Take Away

My sense is that McGilchrist and Seligman are both consonant with each other, and correct. The lurch towards pointed, precise, grasping and single-minded left-brain modes of attention, and the dominance of sincerity over ritual approaches to truth has coincided with and driven the disenchantment of Western civilization. But secular society, with all its rationalism, instrumental rationality and complex (but) one-dimensional, models of the world, has reached some kind of crisis — a point of inflection. Justin Brierley’s intuition that the tide may be on the turn, may in fact be true. For such an inflection to become instruments of God’s grace would intimate a massive civilizational evangelizing event on the scale of the Christianization of England in the 7th century (full disclosure: my saint name is Oswald as in

). And for this to happen, Christians will need to restrain the analytical, grasping specificity and binary approach to truth that is associated with Seligman’s modality of sincerity. In the face of the stifling imperial objectivism and narrowly ‘scientistic’ outlook of modernity, Christians can’t and shouldn’t compete by simply reversing the polarity of this left-brain rationalism. According to McGilchrist, faith can be a route to the re-enchantment of a left-brained world. Re-enchantment requires balancing and inhabiting, simultaneously, world views that are seemingly incompatible: faith and reason; aesthetic and analytical; Christian and secular; liberal and prescriptive; diverse and integrative; Catholic and Protestant; East and West; libertarian and communitarian. Across all of these antipodean categories, one thing is true: human words and concepts always fall short of ‘truth’ and will always be cause for disagreement. When navigating across such diverse epistemological, ontological worldviews, not to mention geography, language, culture and politics — a one-size fits all truth claim is never going to work. Instead, what will be needed is a ritual imaginary that can, gradually, bring that commonality into being.In short, we need bells, whistles, beautiful music, glorious architecture, procession, publicly celebrated sacraments and rites of passage. We need those Old Testament psalms which speak to the whole of creation praising God, to come to life in our Churches, but also in our streets.

“Let the sea resound, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it. Let the rivers clap their hands, let the mountains sing together for joy” — Psalm 98

“The meadows are covered with flocks and the valleys are mantled with grain; they shout for joy and sing.” — Psalm 65

“Praise the Lord from the heavens; praise him in the heights above. Praise him, all his angels; praise him, all his heavenly hosts. Praise him, sun and moon; praise him, all you shining stars. Praise him, you highest heavens and you waters above the skies.” —Psalm 148

We will arrive in the same place of truth not, in the end, by pointed, explicit analytical conviction (although this is important) but through implicit, co-inherence and shared joy. Thomas Aquinas said:

the condition of human nature is such that it has to be led by things corporeal and sensible to things spiritual and intelligible (ST 3q.61 a.1)

Singing together is a corporeal mechanism for bodies and minds to be brought together. Singing hymns, sacramental feasting — and all our rites of passage properly conceived — are ways for the corporeal and sensible to function as iconic bridges to the spiritual and sensible.

Christian unity versus denominational division

There is a real issue of whether ecumenical impetus of nearly all recent popes is about bringing non-Catholic Christians into the fold of the ‘one true church’; or whether, 21st century Catholicism will come to emphasize the true Church (the body of Christ) as an invisible and spiritual reality that includes true believers across many visible denominations. To an extent, Vatican II fudged the issue, teaching that Jesus’ Church ‘subsists in’ the Catholic Church and the apostolic succession reaching back to Peter; but that many elements of sanctification and truth also appear across the Christian fold as a whole. However it was clear — in Lumen Gentium and the Decree on Ecumenism — that the soft edge of this formula came as a result of an authentic recognition of the importance of ecclesial unity and the recognition of what Christians from other backgrounds have to offer.

Speaking as a sociologist, and not very well versed in the byways of Catholic theology, my sense is that right now, esoteric arguments between Christians should take a back seat. If Martin Luther or George Fox could have foreseen the current hegemony of secular disenchantment, materialism/naturalism and unbounded individualism, they might have had pause for thought. And by the same token Pope Leo X might have held back from excommunicating Luther in 1521. Because, at the full tide of Christendom, neither side could appreciate the water in which they swam, they could not imagine Mathew Arnold’s world in which the tide had gone out with a ‘melancholy long, withdrawing roar’. And yet it has — stranding on the shingle all Christians regardless of denomination. In these circumstances, by far the most important task for all churches is to reconstruct a world in which, for the vast majority, belief in the Christian God is second nature; where religion becomes once again the warp and weft for all of culture — the economy, government, health, leisure, youth culture, wildlife conservation, environmental protection, the whole shebang.

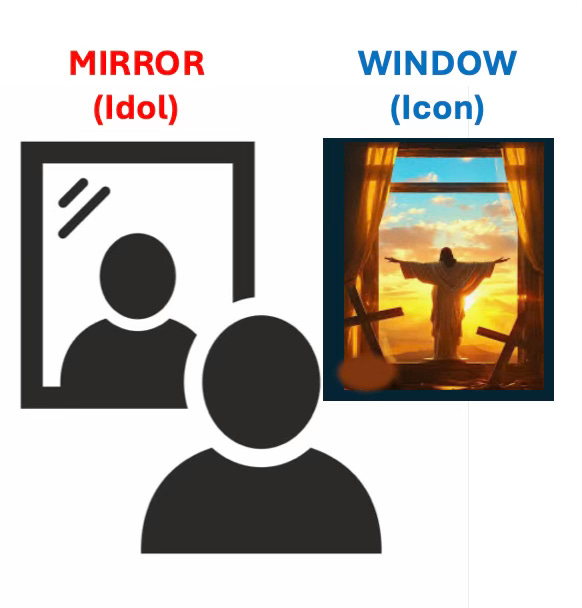

But for the tide to roll back in in this way, suggests a massive and rather rapid cultural transformation — away from hard-nosed materialism and naturalism, away from individualist consumerism and away from purely earthly metrics of personal success (income, career); and towards habits of mind, individual goals and shared communitarian objectives and metrics that rhyme and chime with the Natural Law and point not towards self, as with a mirror but towards God, as with a window.

The Christianization of the Roman Empire — a transformation of a similar scale — took 300 years. And yet, Christianity was making enormous in roads into habits of mind across the empire within just a century, including the treatment and respect for women, children, slaves and sick or disabled people. At the time, the empire was the zenith of human connectivity with ‘all roads leading to Rome’. But for good or evil (and there is a great deal of the latter) the connectivity and integration of the modern world has generated, for all intents, a different social and cultural universe. Economic shocks, technical innovations and even new ideas, can rebuild and unravel our social lives together from the ground up. You only have to consider the impact of the Internet or the smart phone to recognize the scope and scale of systemic cascades: unintended changes that sweep through human systems and cultures almost instantaneously. This is why futures institutes at prestigious universities spend so much time worrying about the potential for mutually compounding ‘polycrises’.

As a Christian with an increasingly skeptical attitude to modernity — and especially environmental crisis and the the prospect of authoritarian AI and transhumanism — I find a silver lining in the idea of cascading change. Given that, with

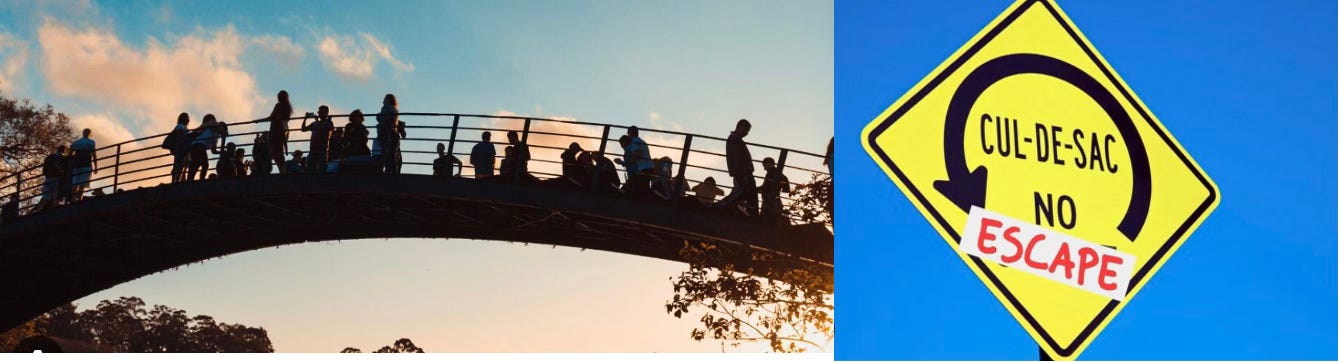

, Christianity and the Imago Dei is in our cultural DNA; and that it is evident even in pathological expressions of identity politics and social justice; it is quite possible that the returning tide could look less like the gentle incoming swell I enjoyed as a child on the beach at Cromer, and more like the Severn Bore (a regular little Tsunami that sweeps at great speed along the tidal River Severn, near Bristol in England).Recognizing iconic bridges and avoiding idolatrous culture de sacs

In the vernacular sense, the Tyne Bridge is iconic — at least for Geordies. For some poor benighted sod stuck south of the river, the bridge is not a destination or the object of desire in itself. Rather it is a conduit to the sunny uplands of Newcastle and North Northumberland (God’s country — or at least a holiday home — for any lost pilgrims out there). Icons lead the eye and the heart through and up to God.

At the same time, any hill walker knows that although the direction towards any distant peak looks straight, the actual path is often labyrinthine, involving side-moves, forks in the road, navigation around obstacles and even frustrating backtracking. You have to learn to love the walking itself as well as the destination.

As Augustine realized, spreading the faith across nations and cultures, and creating a context conducive for evangelism —changing the water of precognitive, vernacular ‘common sense’ —has always required compromises with secular authority. And because the Church is made up of sinners rather than saints, this has always engendered cycles of individual and political corruption, and a temptation to cosy up to the culture; to give up forming individuals and communities, and to allow the church itself to be formed, from without.

In this sense, the North African priests too-easily taking the knee to an provincial tyrant during the Diocletian repression, or to Holy Roman Emperors and their feudal lords, were not dissimilar to Western churches taking the knee to BLM or trans-activism; and embracing the individualism, sexual freedoms, feminism (as opposed to female-ism, or

’s ‘reactionary feminism) and resistance to the authority of tradition that have been associated with popular culture since the 1960s. The shared logic — a kind of modernism — was that you have to ‘go wide’ (however thin) in order to become popular. Donatus’ contrary prescription — was to go extremely narrow and a deep with a view to outlasting the opposition.Clearly this is a difficult line, and the choices have to be remade and recalibrated with every generation. Any fair minded commentator from outside the Christian fold would see that, however well-intentioned, the excessive modernism in the interpretation of Vatican II, as with even more extreme forms of liberalism in the protestant churches, has not limited but accelerated the outgoing tide. By allowing liberal secular states to construe religion as essentially a private matter of conscience rather than shared culture and public policy, they have opened the door to an avalanche of materialist nihilism.

A litmus of this process in the UK would be the abolition of Sunday trading laws by Mrs Thatcher’s government in the 1980s and the disappearance of prayer and hymn from morning school assemblies. But even where there are Catholic school boards (as in Canada) it is now routine to see Pride celebrations, and the flying of Pride flags, as part of the idolatry of sexual individualism— which includes ‘Only Fans’, ‘Tinder’ promiscuity, and sex as commodified pleasure rather than an aspect of marriage and family; and the promulgation of a zero-sum, relativist and anti-western version of history that actively disavows the achievements and universal significance of European Christendom.

Allowing itself to become seduced by the wider culture, the intellectual milieu of Christianity has been subject to forms of moral-theological corruption born of an idolatrous focus on a this worldly materialism, and an often Gnostic-inflected desire to produce utopias here on Earth. The area where this tendency has been most marked relates to the dynamics of individualization, unbalanced egalitarianism (of outcomes) and the feminist denial of the complementarity of the sexes (i.e. equality in difference). According to the standard sociological account, the extension of the division of labour (Emile Durkheim), disenchantment (Weber), individualization (Max Weber, Zygmunt Bauman) and the ‘disembedding’ of tight-knit, place-bound communities (Ferdinand Tönnies, Karl Polanyi, Norbert Elias) comprise the arc of modernization. This has led to a consistent epistemological and ontological error in modernist commentary, namely the focus on the ‘sovereign’ and choice-making individual as the natural unit of analysis. This ontological individualism derives, of course, from the Judeo-Christian Imago Dei. But in Christianity, individual freedom was always conceived in relation to God, and through him to family, neighbourhood, community and strangers. It is now very difficult for moderns, even Christians, to ‘unthink’ the Hobbesian/Lockean/Cartesian/Kantian trope of the self-willed Robinson Crusoe.

Liberalism and Feminism

How has this manifested? Most of all, in the erosion of any sense of the complementarity of men and women, and the feminization of a raft of public institutions with calamitous results. Sometimes an accident of recruitment but more often an ideological project, the practical effect of this transformation has been to obscure the household/family as the fundamental unit of society (rather than the individual) and the fact that, on average, men and women bring very different attributes and capabilities to any problem or institution.

This secular dynamic of late 20th century feminist individualism has now filtered back into the Christian fold leading to the moral-ethical corruption that has seen church leaders endorsing the fiction of gender fluidity and gender affirming health care for childre.4 But heretical gender theologies that have become mainstream in many protestant churches and are making their way into Catholicism, have a sociological root in the prior movement for the ordination of women priests. This movement leveraged a pathological extension of psychological traits that are disproportionately and characteristically (but not exclusively) female. Natural, healthy and vital to the function of human families and society, such traits centre on the propensity for nurture, care, the minimization of harm and the ensuring of fairness (a basic egalitarianism). But with the feminization of many institutions, they have in many contexts become unbalanced, and even harmful and destructive. Gad Saad has characterized the problem in terms of a ‘suicidal empathy’. It is this unbalanced feminization of the Church, along with a series of theological justifications that depart from scripture and tradition, but also evolutionary common sense, that has accelerated the modernist impulse for the Christianity to be re-formed, rather than itself forming the culture. It should be added that this is not necessarily about women per se. Many women have been staunch critics of the process (Mary Eberstadt, Jennifer Morse, Allie Beth Stuckey); and many men some of the most partisan modernizers.

In the long run, the feminist-egalitarian will-to-power in the here and now, will, if unchecked, destroy the Church. The Church of England is one of many already in the grips of such a death spiral. But, given that the social justice shibboleths are themselves deeply Christian derivations of Imago Dei, the death of Christianity is likely, in the end, to prove calamitous for liberals of all persuasions.

In the first century, Christianity spread among women precisely because the assertion of equality in the eyes of God, led Christians to rescue abandoned (female, weak, disabled) babies, to resist the marriage of young girls, to curtail the ability of men to divorce and abandon wives, to reject rape and to insist that men should ‘have sex like women’ — which is to say with fidelity, and within marriage. Christian marriage based on the complementarity of men and women was the greatest feminist revolution of all time. The sexual revolution and the unravelling of the household in the face of an assertive liberal individualism has been disastrous for women and girls. Without Natural Law, liberalism will see a re-paganization of society with all that implies for the relationship between men and women, the treatment of children and vulnerable people and the retreat of universalist ethics in the wake of a new tribalism. This is the Andrew Tate future, and it’s just around the corner, should we take the wrong path. For chapter and verse on this critique of theological feminism see any of the numerous post-feminist, or reactionary feminist critics of the sexual revolution (Eberstadt, 2019; Harrington, 2020, 2021; Lasch, 1997; Morse, 2022; Perry, 2022; Regnerus, 2020; Trueman, 2020; Tucker, 2014; Zimmerman, 2008). For Catholics, the fundamental equality men and women was evident in Jesus’s instruction to Martha to stop waiting on the gathered company, and participate like her sister Mary: ‘Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her (Luke 10: 31). The complementary equality of men and women in marriage, is reflected also in the complementary union of God and his Church. Christ is the archetype egalitarian, but as with the Trinity, the unity is simultaneously a relation of complementarity.

Forming the culture and turning the tide

In the first millennium, following in the steps of the Apostles, the imperative for Christians was to get the word out as far and wide as possible. They achieved monumental success. Christendom formed the moral matrix, the personality structure and common-sense ethics of Western individuals, as well as family structure, the architecture of the state and the aesthetics, economy, leisure patterns and broader culture of society.

Crumbling slowly for decades, there is now a cascading avalanche of cultural and demographic change that could take Western civilization off the map. So this is the problem of 21st century Christianity in the West:

How to operate within, whilst at the same time maintaining a healthy distance from, a corrosive culture, whilst simultaneously rebuilding a parallel civilization in the catacombs.

The girders of such a post-liberal strategy would have to address, head-on, the following:

I — Individualization: The Christian Imago Dei is the source of Western individualism. Shorn of the context of widely shared belief, the nature of individual freedom has changed. Christians understand freedom as being realized through voluntary self-constraint and obligation first to God, and then through God to family, neighbours and community. Having killed God, as Nietzsche predicted, freedom in the absence of meaning, sends people mad. Long term Christian evangelization would have to be linked to a political-economic strategy of rebuilding the ascriptive ties of mutual obligation and reciprocation in daily life. This could include policies such as compulsory local and national service, but also the localization of education systems so as deliberately to enhance the communitarian ‘stickiness’ of communities (as I riffed on here…)

Education in particular could be used as a lever to bond communities and slow down the social and spatial mobility of individuals in favour of the cohesion and sustainability of families and communities. I outline such a strategy here:

II — Feminism: Over the course of the 20th century radical, liberal and socialist variants of feminism have claimed to advance the position of women in a male dominated society. But this claim obscured their dependence on a Cartesian/Rousseauian a priori vision of an abstract rational individual, separate from relations of interdependence and mutual obligation. Severed from motherhood, marriage and extended family, this vision of woman is barely feminine and allergic to both biology and Natural Law. It is hardly surprising that, between Alexandra Kollontai’s ‘collectivize children!’ and Judith Butler’s ‘gender fluidity’, the feminist ideal degenerated into an androgynous vision of nondescript inhuman individuality. this vision is inhuman because, as Aristotle, and even Hume, recognized, our humanity is intrinsically social, interdependent and intergenerational. As both Aquinas and the emerging historical consensus affirms, it is also tied, as with an umbilical cord, to a transcendent God in whose image we are created.

Service and obligation is the new punk rock.

With this in mind, the first order of the new Christian ‘war of position’ — the culture war that must accompany the long march through the institutions — must be a head-on confrontation with the axiomatic precepts and guiding assumptions of feminism. Gramsci’s phrase is appropriate because he conceived his Marxist ‘war of position’ primarily against Catholicism which had a hegemonic grip on the ‘common sense’ of ordinary people. The situation is now reversed. Feminist individualism occupies the high ground. Family-centred, communitarian personalism has been banished to the countercultural fringe. The vision to be articulated centres on the sanctity of motherhood and family life; and of true freedom and individuality emerging from the weft of mutual obligation and a life dedicated to others.

III — Marriage and the sexual revolution: Since the 1960s, the sexual revolutionaries — mainly unmarried, younger women without children — have sold women a vision of male freedom. This was made possible by technological control over fertility through contraception. The message was not only ‘have sex like men’ but live and work like men, self-actualizing through careers, power and control over others. In the face of the obvious biological problems of delaying fertility, science has come to the rescue with ever more esoteric reproductive and fertility technologies — from egg freezing and in vitro fertilization, to surrogacy and, in the near future, in vitro gestation. But as intimated above, none of this has made women happy. In fact there is an enormous literature detailing the opposite: the depth of mental anguish, depression and physical ill-health that has accompanied this transformation. Subscribe to

for the complete story and all the facts and figures — or just talk to your mum, grandma or unmarried 40 year old friend without children, or 21 year old niece desperately trying to find a decent bloke to marry and have kids with, or her brother who is addicted to porn, allergic to commitment and scared of actual women. The academic literature is in the references.With this in mind, Christians have a mountain to climb which starts with a vigorous and unashamed defence of traditional marriage and large families. Within communities, the Church should prioritize finding ways to support young families and large families — encouraging young people to get married younger with a deep lifelong commitment. This is much harder, and perhaps impossible, in highly mobile, individuated and placeless urban communities. It becomes easier to the extent that mobility slows down, interdependency and commitment starts early and place-bound communities develop a rhythm that works its way into people from childhood. I have drafted a few suggestions as to the mix of policies that might push in this direction here — in this case in relation to education.

Catholics are always going to be animated by such issues as contraception and abortion. However, the early Christians didn’t go head to the head with the Roman state demanding an end to slavery. They changed the culture gradually and inexorably by practicing the logic of Imago Dei in every day life — caring for the sick rather than running from plagues; adopting baby girls or disabled children who had been abandoned to die; eradicating male-instigated divorce and consolidating fidelity in marriage etc. In the same way, much more important than legal victories won through bureaucratic political machinations, is the establishment of a lived and joyful reactionary counter-culture which infiltrates the ‘common sense’ of ordinary people. This is what Gramsci understood by counter-hegemonic strategy. It doesn’t start in political parties and legal challenges. Laws can always be repealed. It starts in Church, but also house-parties, barn dances, pubs and leisure associations, school PTAs — which is to say with culture.

IV—Consumerism and materialism: Since the Second World War, faced with the threat of communism abroad and socialism at home, Christians have tended to throw in their lot with centre-right political parties: Republican, Tory, Christian Democrat etc. This has also mean a kind of wedlock to the (classical) liberal idea of Market Society. But in the absence of a shared foundation of Christian virtues, market economics and the consumerism have become the most effective promulgator of materialism, rationalism and transactional individualism. In this sense, whatever their formal appellations, Conservative and Christian Democratic parties are just as much part of the liberal firmament as their antagonists on the left. Pretty much everyone has been some kind of liberal since 1945.

Capitalism has transformed the world. Disembedded price-setting markets are the most efficient mechanism for the allocation of resources and labour. Driving technical and product innovation, market society has created a modern world that (only a) few would be willing, voluntarily, to abandon. Any new Christendom needs markets, technology and innovation. However, from a Christian perspective, there are four problems with Market Society. Mostly these are about trade-offs and a matter of degree.

SCALE: Functional and spatial integration can greatly increase productivity and the rate of technical innovation. But economies of scale also undermine the autonomy, sufficiency and dignity of families and communities. Other things being equal, the structure of economic regulation should maximize decentralized domestic and community scale manufacture and processing. A Christian political economy would act to: unravel the tacit corporate monopolies exercised through product design which deliberately preclude home-repair and maintenance; dismantle state regulations that impede small scale, micro or domestic manufacturers; and restructure the tax and regulatory system such that the burden decreases with the declining scale of the enterprise — to near zero for domestic, family enterprises.

SCOPE: Although dynamic markets are good, they should not encroach entirely into all areas of society and culture.Through a combination of legal regulation, social norms and cultural pressure, some domains should be partly or entirely outside the ambit of markets. Sex and pornography are examples hard drugs. Some natural and social goods should not be commodified — period.

GRADE/MIX: We are used to thinking in terms of abstract, anonymous price-setting micro-markets in which supply and demand curves are continually resolving through an infinity of impersonal, decentralized transactions. This ideal-typical picture, that is presented in every Micro Economics 101 course, was the liberal utopia described by Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation. It was the pursuit of this abstractly beautiful and rational ‘hidden hand’ that would transform private vice into public virtue that drove ‘disembedding’ of English rural economy and the enclosure of the commons — as I described in this earlier post:

As Polanyi detailed at great length in his later anthropological work, markets are as old as humanity. However, prior to capitalist modernization, they tended to be embedded i.e. integrated in complex ways to all the other domains of life — leisure, marriage, kinship, religion, politics. What this means is that the abstract price-setting markets are only one means of governing market exchange. Small-scale, place-bound markets and market-places may come with an opportunity-cost in terms of the scale of productivity gains. But they are much more likely to be generative of the human-scale, family friendly and bottom-up patterns of communitarian care, mutual aid and reciprocation, without which Christian life is impossible. Right now we need more embedding and less dependence on free-wheeling, global corporations.

‘Right wing’ (market liberal) Christians should remember the roots of the word ‘economy’. The Greek ‘Oikonomos’ really meant something like ‘household rules’ — the normative conventions governing the just allocation of resources within a community. We understand this definition perfectly in relation to the money economy. But there are other ‘economies’ — bodies of household rules — that have lapsed from view. So for instance, by the ‘sacramental economy’, Catholics understand the ‘communication … of the fruits of Christ’s Paschal mystery in the celebration of the Church’s ‘sacramental liturgy’ (Catechism of the Catholic Church, # 1076). There is nothing wrong and much good with the money economy. But there other economies — sets of ‘household rules’ — that relate not just to sacramental liturgy, but neighbourliness, family obligations, hospitality for strangers, stewardship of creation (the environment). Christian political economy is about balancing (and continually rebalancing) these sets of rules — in a way that is faithful, flexible and iconic, which is to say always orienting our gaze out of the City of Man and towards the City of God. As with Augustine’s battle with the Donatists, it’s always about trade offs, (fallible) judgements and the particular context —and it inevitably becomes political, and potentially corrupting. Welcome to the Fall.

METAPHYSICS. Liberal market ideology is predicated on choice-making, transacting, sovereign individuals. As a derivation of the Imago Dei, this conception of individual agency is sometimes good. But in a secular setting, it quickly morphs into the elevation of an idolatry of self — narcissism writ large. Linked to aggressive materialist and naturalist accounts of the universe which preclude any kind of supernatural agency, transactional ideology of market society lends itself to an acceleration of the ‘meaning crisis.’ Over time the, with instrumental logic of transactionalism, this libertarian materialism begins to rationalize the treatment of other persons as a means rather than an end — destroying immediately the precious insight of Imago Dei. This is basically why, in the absence of a deeply embedded Christianity, any kind of liberalism ends up with celebrities like Andrew Tate — who would have been perfectly at home, thumbing down, in Rome’s Circus Maximus.

By the same token, in the absence of a shared virtue ethics that codifies the sanctified goals and meanings of our shared life, liberal individualism gravitates to Main Street materialism. And as a result retail therapy and consumerism are the dominant forms of idolatry of our age — possibly the single most significant barrier between people and God. Wealth and consumption is such a powerful idol that whole churches have been suborned by the Devil (to invoke an old fashioned but accurate picture of the world) into preaching the ‘prosperity Gospel’)

ICONIC BRIDGES:

So problem for the Catholic Church — and all Christians — at least in the first instance, is bums on seats. This is important, because each ‘bum’ is potentially a person saved. But it’s also important because without critical mass — the weight of faith within communities — forming the wider culture and turning the tide is much more difficult. So the question arises how to create a strong independent and intergenerational culture, forming individuals, strong in catechesis, affirming of faith and creating opportunities for healthy courting and marriages and child rearing —separated from but also connected to the wider culture by an invisible, but impregnable, ‘semi-permeable membrane’. Our culture has to be both different and attractive. Different enough to maintain its shape, identity and mission in a culture that is, often deliberately, corrosive; but not so different that the gap can’t be spanned by the bridge of evangelism; and sufficiently attractive — alluring, attention holding — that non-Christians feel the compulsion to cross for the first time, or perhaps return to the fold.

Based on the discussion above, I’m going to open myself to criticism and probably ridicule (Pollyanna!) by throwing out a few suggestions. Here they are, in not particular order.

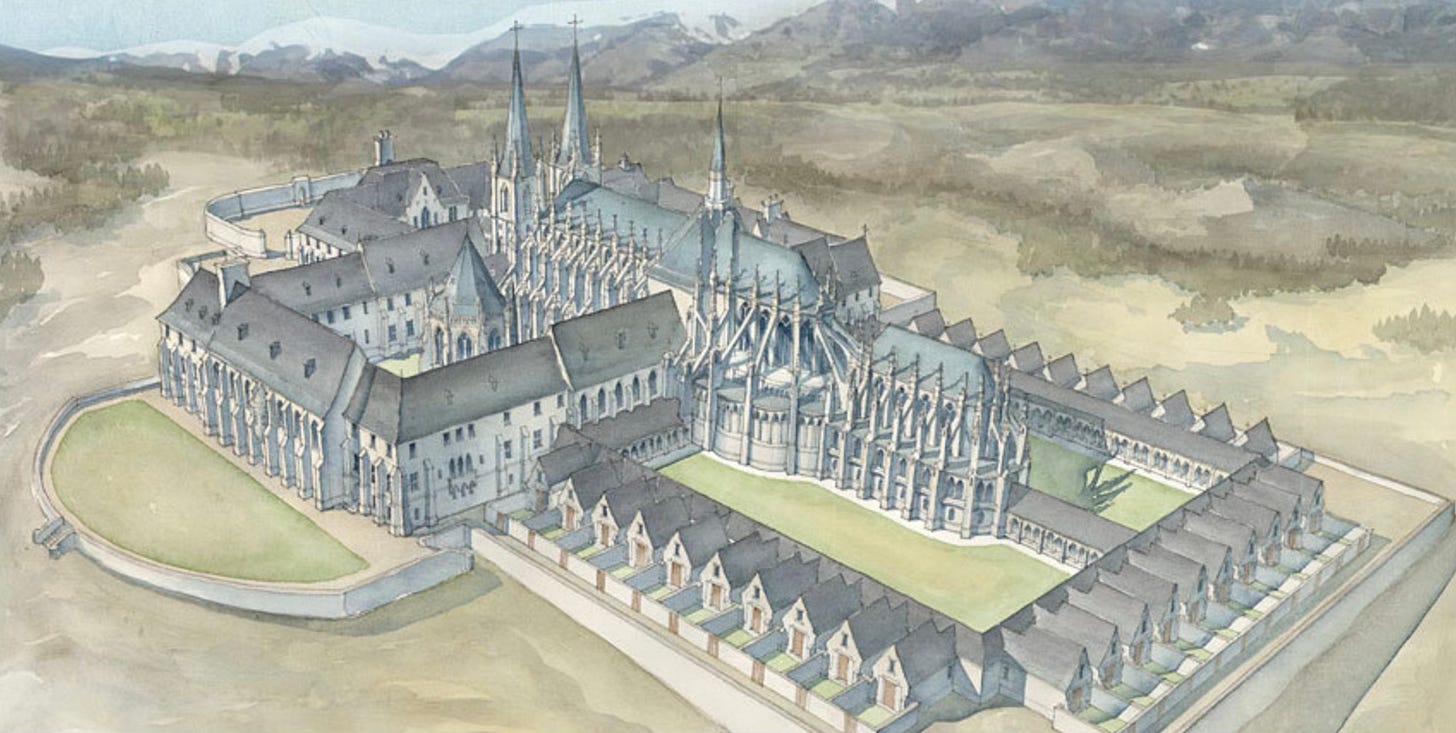

Church should be special, separate, liminal and beautiful: In the context of hyper-individualization, liquid modernity, colliding diversity and the deep rationalized disenchantment of secular society — facts and logic will never be enough. Following the logic of Seligman and McGilchrist, but also Jordan Peterson and Jonathon Pagaeau, now is the time for Christians to lean into mythos and the God-given power of the human imaginary. This means embracing the ritual/aesthetic modality — in all its manifestations. It means leaning into the right-hemisphere modality of the exploratory, adjacent, provisional and implicit meanings of beauty. The traditional Catholic formula of the True, the Good and the Beautiful means rejecting ugly architecture and service. It also means embracing large-scale ambitions to build new churches and monasteries, hospitals and alms houses, whilst insisting on the integration of the spiritual, sensuous and sensual. As with the Gothic wonders of Christendom, any Cathedral should be an intergenerational, communal project taking lifetimes to build. This approach pays off. Compare Gaudi’s Familia Sagrada in Barcelona with any project-managed, Church-corp PLC modernist monstrosity knocked up my ACME Christianity in the last 50 years.

Ambition combined with humility is the mother of beauty. This prospective Carmelite Monastery in Wyoming is an indication of renewed spiritual confidence.

If Wyoming can build on this scale, then so can and should every Catholic parish. To this end, Bishops and priests in any Diocese should seek to involve the laity in the formulation of really ambitious objective which require the participation or all parishioners over years, brick by brick — through fund-raising barn dances, physical contributions to construction — with visible and joyful celebrations of each milestone, and contributions of each school child, church elder, parent, deacon and priest memorialized the physical fabric of any construction. It is this journey that provides the anthropological vehicle for faith and communitarian conviviality and care.

The liturgical service: Liturgy should be beautiful and transfixing. Literal cognition, explication and understanding (left brain) should be balanced by aesthetics, rhythm, drama and harmony. Partly this means recovering musical and liturgical traditions often left-behind by modernist populism. In ecumenical vein, it should also encourage different denominations to draw upon the best each has to offer: the traditionalism of Catholic and Orthodox bells and whistles, Latin Mass, candles, incense, choral music — but also the glorious English Hymnal and congregational choir of the Anglo-Catholic tradition, the working class choral music of Welsh methodism, the Iconography of Orthodox and liturgical procession of Eastern Catholicism — and the silent contemplation of the Quakers.

In the context of the ‘meaning crisis’, the diagnoses of McGilchrist and Seligman suggest very clearly that implicit messaging that works on the senses, on the body (through participation), through the drama of ritual and through aesthetics is much more likely to generate cascading cultural change.

Congregations: Protestants might well be advised to recalibrate their allergy to ritual and aesthetics. On the other hand, Catholics have a great deal to learn from the congregational approach to place-bound parish communities. Catholicism is good (at least in principle) at generating a Catholic identity that translates easily between parishes, language-cultures and societies. But Catholic parishes seem to struggle to build cohesive, face-to-face anthropological communities associated with particular places and neighbourhoods. I suspect this is partly because Protestantism was born into (and drove) the liquid-modern society of individuals. The Catholicism of medieval Europe didn’t have to build place-bound communities because far fewer people moved more than a few miles from where they were born. Face-to-face conviviality and ‘we identity’ was a taken-for-granted aspect of rural life — which is to say, the life of nearly everyone. Mutual identification in relation to parishes rather than just shared Catholicism requires a kind of social entrepreneurship and the active ‘breaking of bread’ in the neighbourhood as well as during the liturgy.

Traditional, liturgically specific music: Right off the bat, let’s get rid of the guitars and tambourines. Let’s winnow mid-20th century hymns with clumsy pastiche lyrics which often don’t scan. With centuries of material in the Catholic back-catalogue as well as a wealth of perfectly theologically sound and beautiful Anglican hymns and choral music, there is little excuse for what Bishop Barron calls ‘beige Catholicism’. Church music should be hallowed and specific to place and occasion. Christendom has produced a monumental array of musical idioms, all of which have their place. The single universal qualification should be the devotion of time and resources to getting it right. This applies however big the church — even if there is just a single cantor.

Music and bums on pews: Every single parish has a school. Most have a Catholic Women’s League or a branch of the Knights of Columbus, and the Church has financial resources. The over-riding strategic and evangelic imperative of the Church in the West — any church, any denomination — must be to put bums on the pews. Without a critical mass of young people, it’s almost impossible for the Church to provide a rich, attractive form of life, with its own common sense — an immersive normative bath, deep enough to provide a counter-pole to TikTok, Instagram, Spotify, Tinder and Only Fans. This means two things. Bringing kids into the life of the church and giving them responsibility — with demanding goals and objective (‘Build us a Familia Sagrada!’). But also making the liminal and spiritual space of the Church and the liturgy an overpowering sensual and sensuous experience. The answer is very clear. Christian schools should made responsible for bringing high standard Christian music into the Churches. Every single school has sufficient musical children for this to be possible.

posted a short clip of what it can sound like. Take 5 — and listen!

For those who doubt that the ordinary bricks of an average school assembly can be used to build such a musical cathedral, I refer you to a BBC series call The Choir starring a nerdy young choral scholar, Gareth Malone, who take it upon himself to introduce choral music to some of the most deprived schools and communities in Britain. Needless to say, he succeed beyond all imagination and they end up at the world championships in China. What Gareth showed was what every Christian community used to know, namely that with consistent support, a good teacher and the right incentive package — wonderful church music is merely a semester away, and sublime, just a couple of years.

Will the bishops, deacons and priests, and we laity, please step up….Music is an ‘iconic bridge’ both directly to God, and through community and each other — to God.

This is what we need to do.

(a) Train young pianists and organists: make sure there is a target for each Parish

(b) Set each Parish and school board a target — for fundraising to pay for a choral director. Each school to have a functioning choir within 2 years, providing music for the church

(c) Create travelling ‘super choirs’ — to go around schools showing kids and teachers how great it can be — and to explain why it is so important.

(d) Encourage (mandate) choirs to turn out for local weddings and funerals, and to sing in public

(e) Create a structure of competitions and events, including trips abroad — to sing at some of the great Cathedrals

(f) Treat this mission as existential to the survival of the Christianity in the West — because it is.

(g) Make sure that the same young musicians can double up to play barn/square/line dances on a Saturday night — because young people also have to party, court, play and propose to each other, and that doesn’t happen in but adjacent to church.

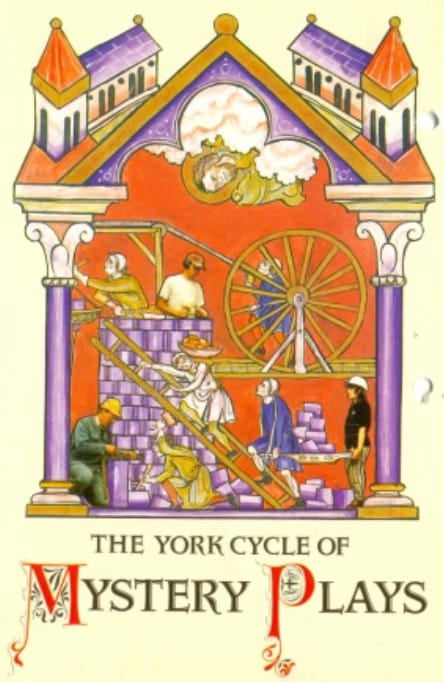

The Church should reclaim the public square: Prior to the English Reformation, medieval Catholic society revolved around place-bound, rural communities — the church and the market square. Everyone participated in a common culture. There was nothing like the division between high and low art understood in terms of class. Rather art and music was functional, relating to particular occasions — the liturgical cycle, the seasons, the pub, weddings, funerals, baptisms, walking and working. And most people had access to most of the repertoire, in one form or another. Parish life was highly involving, and religion was public and ascriptive. Numerous feast days organized punctuated the liturgical year and were accented by the particular patronage of particular guild associations for particular saints. Longer cycles of mystery plays involved participation by the whole community. Important religious festivals were often accompanied by processions through, around and between towns and villages. Pilgrimage was as often a high point expression of piety — sometimes once in a lifetime — but also an exciting adventure.

Each diocese should be give responsibility for re-introducing to parishioners some aspect of medieval drama and aesthetics: a single public, celebratory, anthropologically rich, liturgically sensuous ascriptive rite of passage — procession, sacrament, drama, celebration. The more people involved, the better. If clergy have performance evaluations — heaven forbid, a terrible idea — the metric would be the extent and depth of public participation and the level of ambition. Why should Canada or America not initiate a rotating cycle of community-based mystery plays? As with our Churches, we should aim for the sky.

Christian care and covenant: If the secular age is marked, as Charles Taylor argue,s by the privatization of religion behind the veil of individual conscience and belief, Christian evangelization must take back initiative, and the weft of mutual obligation, from the state. Prior to modernity, the obligation to care for the poor and the sick was not devolved onto abstract state authorities and mediated by digitized fiscal transfers. It involved life-long relationships, person interactions, face-to-face encounters, patterns of mutual obligation — it was in other words both public and personal. We have devolved personal responsibility to the state. Catholics need to take it back. The most impressive counter-example of this is the 900 year old continuing tradition, in the Belgian town of Geele, of (hundreds of) ordinary families undertaking life-long care for mentally ill people. It’s incredible, inspiring, and they make it work — quietly. In pre-Reformation England, ‘tramping the parish bounds’ — a ritual procession around the borders of the Parish — clearly marked out the ambit of responsibility for local parishioners.

‘These people, in this place, are yours and you are theirs.’ Perhaps it is time we recovered some of this loving constraint on our personal freedom. Communities, just as with babies come, with strings attached.

Is this realistic? Probably not! But in a time of economic slowdown and fiscal crisis a model of ascriptive local service for providing all the personal care for patients might start out as a catastrophic loss of service and turn into a blessing of participation. However, there is one little tweak that can make such innovations much more likely to succeed. This simply leverages a threshold effect.

People are much more likely to do something if it is guaranteed that (a) lots of other people will take part, and (b) the ultimate impact will be great.

If you ask Bob to volunteer at the hospital — he may well find an excuse. If you ask 100 people at Bob’s church to volunteer, with the caveat that no-one will set foot in the hospital until there are 100 willing volunteers, then Bob is much more likely to stick his hand up…..or in his pocket…or to get involved in myriad other ways. Once the ball is rolling, it will develop momentum and in time carve its own groove. Under Christendom, the ball rolled for 1500 years.

Politics and secular power: Just as for the Apostles, the early Martyrs, Augustine and Aquinas, all of this does means a dangerous but necessary engagement with secular authorities. The vision of more viscous, ‘sticky’ and place-bound Christian community tied by patterns of reciprocation and mutual obligation, is not easily reconciled with ‘liquid modernity’. Greater diversity, mobility and multiculturalism make it much harder. Christianity has always been multi-ethnic. Declaring that there was ‘no longer Jew or Greek’ (Gal. 3), Paul underlined Imago Dei as the basis for the original, and only true, form of internationalism: an assertion of kinship in Christ that was able to loosen the grip of clan and tribal thinking. It was this that enabled Christians to aspire to the generosity of the Good Samaritan. But scripture in both Old and New Testaments also points to legitimate trade offs: the concentric rings in the ambit of moral responsibility. For example in Timothy:

“If anyone doesn't provide for his relatives and especially for members of his household, he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.” [1 Timothy 5:8]

So it is complex. Certainly any plausible civilizational evangelization would in the end involve Christianity re-establishing a privileged position in national life. And given the current trajectory of immigration and demography, this would probably involve, for instance, challenging Islamic occupation of public spaces for praying and aggressive public displays of proselytization and intent. In an elegy to localism, differentiation, context, particularity, against all forms of imperial universalism, abstraction and ‘left-brained modernism’ Iain McGilchrist argues that it is the nature of human beings to yearn for:

Belonging to a trusting, open-door community

Belonging to and contact with nature (rather than ‘abstract environment)

Relation with the Devine

This, again, intimates complex trade-offs between the imperative to honour all humans (and strangers, samaritans and even enemies) qua Imago Dei, and the nested laters of interdependence and mutual identification that are necessary for ‘open door’ relationships of trust. However, this essay is too long already, and the issue is sensitive and complex, so I will defer consideration to a future post.

A parallel but outgoing counterculture: Christianity does need its own spaces and culture in order to create a robust vernacular way of being that is not swamped by the culture of cynical materialism and individualism.

This means places to sing, to court, to drink, to celebrate feast days, to celebrate rites of passage and to nurture and care. Given declining head-counts, courting and youth culture must be priority. Generational continuity has seen the Church grow in number from 12 to 1.4 billion Catholics and 2.4 billion Christians. In our despondent, free-wheeling, rationalizing ‘secular age,’ bums on pews, marriages and children are the only metric of evangelization that count. Churches in the UK have been buoyed by Christian immigrants, giving rise to a misplaced confidence. If the culture is corrosive of faith, and these immigrants as assimilated to the culture, the blip will be local and temporary.

Final thought

All engagements with the wider culture should be tested. Are they Iconic bridges or Idolatrous cul de sacs? Idolatry, in this sense, is anything that stops with the self, with the immediacy of worldly desires and objects, which leads to a dead-end. Iconic bridges lead somewhere — to a different reality. Our material world — Creation — is good, and beautiful. God made it for us. But all our engagements with the world, whether in Church with the liturgy and the sacraments, or in our work, or in relation with our neighbours, or with friends, or girl/boyfriends or spouses and children — should open a window to the divine life in Christ. And with this in mind, everything that we build together should be forged reverently and beautifully with this in mind.

References

Eberstadt, M. (2019). Primal screams : how the sexual revolution created identity politics. Templeton Press.

Harrington, M. (2020a). Incels could become the new Vikings Our culture is creating a flotsam of sexual no-hopers-with disastrous consequences.

Harrington, M. (2021). The sexual revolution killed feminism Fetishising freedom harms us all moveincircles. https://unherd.com/2021/11/the-sexual-revolution-killed-feminism/

Lasch, C. (1997). The sexual division of labour. In E. Lasch-Quinn (Ed.), Women and the Common Life: Love Marriage and Feminism (pp. 93–120). Norton.

Morse, J. R. (2022). The Sexual State: How Elite Ideologies Are Destroying Lives and Why the Church Was Right All Along. Tan Books.

Perry, L. (2022). The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A new guide to the 21st century. Polity.

Regnerus, M. (2020). Cheap sex : the transformation of men, marriage, and monogamy. Oxford University Press.

Trueman, C. (2020). The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism and the Road to the Sexual Revolution. Crossway Books.

Tucker, W. (2014). Marriage and civilization : how monogamy made us human. Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Zimmerman, C. (2008). Family and Civilization. ISI Books.

These first two paragraphs I am riffing on a pithy and illuminating treatment in Bauerschmidt, F.C. and Buckley, J.J. (2017) Catholic Theology. An Introduction (Wiley)

It’s a little amusing that some 1000 years later, Calvinists adopted a similarly rigorous approach to the business of piety on the basis of the opposite soteriological predicate: that faith alone and God’s grace, and no measure of good works, could secure salvation.

Thus for instance, a sincere approach to engaging two mutually hostile parties in conflict, at least with the Quakers, would probably rather rationalistically assume that there must be some overlap and basis for agreement. The process of looking for consensus then circles this for as long as it takes until an agreement is forthcoming. The assumption is that this place of consensus is authentic and ‘true’ to both parties. A ritualistic approach accepts that the two moral universes are both real and mutual incompatible. But without trying to resolve one to the other or to find a large scale meta-truth, it simply bypasses the obvious night and day incompatibility of two worldviews or vantage points, but attempts to ritualize some small insignificant point of agreement about the process. Seligman would argue that ‘have a nice day’ doesn’t really mean ‘have a nice day’ but rather something like ‘let’s both temporarily act as if we are in a world where you care about my day and I care about yours.’ , This apparently meaningless ritual then proceeds to do real work in oiling the wheels of daily interaction (and whatever business is at hand). In the same way, in a process of mediation, it might be enough to agree regularly to sit in the same room and have a cup of tea, without any overt attempt to secure an authentic agreement. But — like magic — this ritual leaves room, behind the scenes, for McGilchrist’s ‘right brain’ mode of attention gradually to reframe the relationship such that an agreement may become possible, even if only an agreement to disagree in peace. This right brain leading left brain scenario is, at least to my mind, a body-leading-the brain approach. It reminds me of dog trainer who, faced with two dogs who hate each other, walk them side by side. For a dog, face-on eye contact is aggressive, and a dog in that position must be a potential aggressor. Whereas another dog trotting at one’s shoulder must be a friend… because that is where friends would be. So placing the two dogs-bodies together in parallel, shoulder to shoulder, subverts their mutual aggression and switches both into friend mode.

Arguably, earlier incarnations of feminism were much more realistically rooted in the Natural Law of complementarity, and were protesting the unbalancing of this relation by the dynamics of industrialization and the separation of work from home, career from parenthood.

You could perhaps use the example of the benighted character featured in these two references where he defines who the "enemy" is. He is also very much into the project of re-Christianizing Amerika.

http://www.thenerdreich.com/unhumans-jd-vance-and-the-language-of-genocide

http://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2024/03/08/cpac-attendees-america-under-attack

Vance is of course closely associated with Opus Dei as are the people associated with and linked into the First Things outfit with which Paul Kingsnorth is also associated

These two new books describe the dark behind the scenes machinations of Opus Dei

1. Stench by David Brock

2. Opus by Gareth Gore

Some/many of the principal movers and shakers of the now notorious 2025 Project are closely associated with Opus Dei, as is Leonard Leo the number one honcho of the Federalist Society.

This reference joins up all the dots

http://opentabernacle.wordpress.com/2024/09/02/opus-deis-influence-on-project-2025

I appreciate the work that went into this. I look forward to reading it in full when I get the chance this evening. Thanks for the mention! God speed.