First and second breakfast...and sleep

On the modern parsing, zoning, dissecting, disassembling that is driving us mad.

Homeschooling hobby farmers and small-scale desk top manufacturers skip to the last paragraph for a vignette which may capture aspects of your life.

Sleeping and eating naturally and socially

The distinction between ‘first’ and ‘second’ breakfast immediately brings to mind Hobbits. ‘First’ and ‘second’ sleep — frequently crops up on the BBC when they need a titbit of a story about how the past is a different country and they do things differently there. But when you think about it, the sleep thing really does get at the strange and disembedded quality of modern life. The classic study was conducted by Roger Ekirch:

Both phases of sleep lasted roughly the same length of time, with individuals waking sometime after midnight before returning to rest. Not everyone, of course, slept according to the same timetable. The later at night that persons went to bed, the later they stirred after their initial sleep; or, if they retired past midnight, they might not awaken at all until dawn. Thus, it ‘The Squire’s Tale’ in The Canterbury Tales, Canacee slept “soon after evening fell” and subsequently awakened in the early morning following “her first sleep”; in turn, her companions, staying up much later, “lay asleep till it was fully prime” (daylight).

The jury is still out, but according to Ekirch (interviewed here), the period of wakefulness would last up to an hour, sufficient for Matins prayers (2-3 am), to study or, often, to have sex.

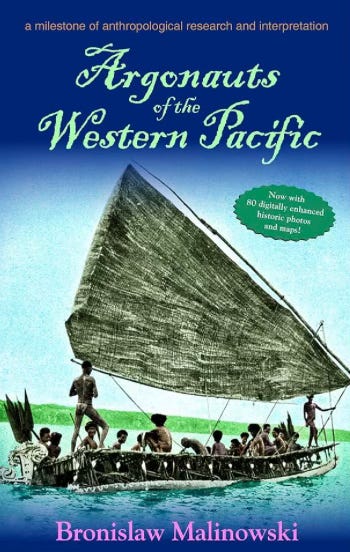

Thinking of Bronislaw Malinowski’s famous study of the Polynesian ‘Kula’ ring of trading islands and partners — Argonauts of the Western Pacific — Karl Polanyi realized that a principle feature of modernity was the ‘disembedding’ of economic life. The Kula was an institution of trade and relation weaving together a ring of 18 island communities, and covering thousands of square kilometres. Thousands of participating Polynesian men undertook epic trading voyages twice a year, once to the island on the left and once to the right— ostensibly to pass on a gift to life-long Kula partners on the neighbouring islands. The gifts circulated, hand to hand, in perpetuity. Partners were construed — through ritualized pairing and rites of passage— as symbolic kin. The circulation of the ritual gifts — red shell-disc necklaces (soulava) in a clockwise direction, and white shell armbands (mwali) moving counterclockwise — made possible a parallel and more economic/utilitarian barter of more mundane items (gimwali).

The economy, weather, religion, politics…as ‘things in themselves’

For Polanyi, the most significant feature of this story related to the category of the ‘economy’ per se. You know a modern society by the existence of an ‘economy’ — a domain of production and trade that is rationalized, highly instrumental; that is a bounded, separate domain governed by its own rules; and that is understood and talked about by ordinary people as a such a bounded domain i.e. ordinary bods could have a breakfast conversation about ‘the weather’ or ‘the economy’: ‘How’s the weather over there!’.. ‘The economy is looking dodgy’.

For a more detailed treatment of Polanyi and embedding see this earlier post

It’s interesting that I immediately had recourse to ‘the weather’ to intimate this character of this archetypically modern conversation, because ‘the weather’ as a bounded, separate phenomenon governed by its own rules, is also a distinctively modern idea. From the vantage point of a participative worldview, ‘weather’ would simultaneously and indivisibly pertain to the spiritual charge of the entire world, including of course the mood and balance of local gods. Owen Barfield (Inkling BFF of CS Lewis, and father of Narnian Queen ‘Lucy’ ) used the history of word to explore the deep history of civilization as a transformation from a ‘participating consciousness’ to the characteristic detachment and withdrawal of spiritual awareness that we now take so much for granted, that it is impossible to un-think. In this long transformation, Barfield detected the separation of inner (psychological, spiritual) and outer (objective, material) qualities in phenomena. Thus pre-modern Germanic tribesmen would not have distinguished in a clear way between the material phenomenon of wind and the metaphysical, spiritual aspect of ‘spirit’. The use of the same word was not a case of metaphorical extension (the thing we call ghost being ‘like the wind’). Rather, according to Barfield wind and spirit were a unitive phenomenon.

I won’t go into Barfield’s deeply fascinating account in any detail (but you will be well rewarded reading Mark Vernon’s book or following poet, priest and rock&roller

here on substack). Needless to say, the process of withdrawal and the emergence of a material, objective world that is available for modelling, dissecting, use and abuse is very much part of the story that (Iain McGilchrist) has recounted about later modernity as an unbalanced and possibly unsustainable, over extension of the left-brain modes of cognition and attention.Modernity as dissembling and re-assembling

It’s funny how it is all coming together. Ideological contestation apart — functionalist versus conflict models, Marx versus Weber, theories of industrialism versus capitalism — there is a deep and settled consensus that modernity comes with a psycho-affective and spiritual price-tag.

Individualization; Disenchantment (Max Weber)

A loss of shared, public meanings (Charles Taylor)

The erosion of shared, affective place-bound community and social capital (Ferdinand Tönnies; Robert Putnam; Robert Nisbet).

Anomie, the division of labour, the loss of mediating institutions and a propensity for meaninglessness and suicide (Emile Durkheim)

Alienation (the younger Karl Marx)

Psychological repression (Sigmund Freud, Norbert Elias)

The over-weaning dominance of sincerity relative to ritual modes of engagement (Adam Seligman)

Atomic detached individualism and the loss of participation (Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, Owen Barfield)

Narcissism (Christopher Lasch)

Pathological and ubiquitous therapy (Phillip Rieff)

A pathological over-extension of left-hemispheric modes of attention (Iain McGilchrist)

The unravelling of marriage and family (@louiseperry)

…and so on. I could go on. There are many consonant strands in this weave. However, here I simply want to draw attention to Karl Polanyi’s version of the same thing and elaborate what I think is an important, and perhaps the most important, aspect of modern civilization (big claim I know — but bear with me).

Disembedding

The process of ‘disembedding’ that began with the enclosure of the English commons by rapacious, early-modern sheep farming aristocrats — saw the creation of three fictitious commodities: money, land and labour.

For a more detailed exposition of Polanyi and modernity as disembedding see my previous post below

These were fictitious because they were not created for the purpose of trade and exchange. In any event, the impact of ‘The Great Transformation’ was to create an ‘economy’ as such. In medieval Europe ‘labour’ and ‘land’ were intimately tied together in the indivisible social and cultural pattern of life organized around the rural estate. Rich people could own and even buy and sell land. But it was never unencumbered free title that we would understand now by the designation ‘freehold’. Land came with villages, churches and responsibilities. Medieval villains (in the older sense) were landless, but not without rights — or responsibilities. Their subsistence was intricately codified by the fine-meshed regulated use of common lands, obligations to the land-owners, rights consequent upon parish membership. By modern standards, nobody, rich or poor, was ‘free.’ By kicking peasants off the land and enclosing the commons, capitalist modernization eventually created, almost ex-nihilo, the three fold distinction between the State, the Market and Individual citizens— the latter construed as sovereign, free-wage labourers (even if as Marx pointed out, the ‘choices’ were often somewhat illusory).

For the canoeing, venturing Polynesian neighbours, every aspect of life was simultaneously ritual, religious, social, cultural, political, familial, public and private — interior (‘emic’) and exterior (‘etic’). The demarcation of different zones — inside/outside, economy versus ritual/familial — would simply have been incomprehensible. Preparation for each trip involved the construction and preparation of ocean going canoes, rituals, all manner of crafts, sharing of resources, relations between in-laws and out-laws, the application of aesthetic choices and the creation of ‘art’, food and feasting, singing. In a not dissimilar way, Eamon Duffy (who I have mentioned before) describes how, on the eve of the Protestant Reformation, the rich complexity and nuance of a Latin liturgy worked out over 1500 years, met with a sustained, bottom-up, communitarian response from the laity — para-liturgical processions, plays, candle purchasing, all-night vigils to guard the sepulchre containing the Host, corporate/guild sponsorship — which combined ritual, religion, social, cultural and ‘economic’ aspects of the life of a village, in a sustained and integrated participate whole. Secular (not quite yet) ‘sport’ (e.g. Shrovesday football) dramatizing aspects of Christ’s battle with evil. Public displays of piety gave vent to increasingly rich interior psychological dramas of private faith (and doubt); but also — as with the communal drinking that accompanied some of the vigils or the sacred bonfires — created opportunities for joyful social interaction (or what Edith Turner, remembering her husband Victor’s ‘anthropology of collective joy’, called ‘communitas’). Other para-liturgical traditions, channelling what Huizinga called the ‘ludic’ play element in culture, created an accidental but enormously entertaining opportunities for courting — as with the habit of gangs of teenage gangs of boys or girls, ‘kidnapping’ one of their opposite number and demanding a ransom for the church fund or local Corpus Christi feast.

The same joyful polyvalent character also applies to the economy. Feast days involved days of work. Their number grew throughout the period into the 1600s — involving real costs for landowners Corpus Christi for instance, was associated with a non-negotiable week long holiday for fasting, processing, feasting and all the various para-liturgical accretions. So once again, for historians and economists looking back, it would be a real mistake — a category error — to try and look at this tissue of activity and associated mentalities (to use Marc Bloch’s term).1 There was no ‘economy’ as such, no ‘religion’ as such, no ‘dating culture’ as such — but rather a complex, seamless constantly reformulating whole. Pulling on one thread, would immediately communicate a tension to the entire tangled ball of wool. That is really what the ‘embedded’ society, whose unravelling Polanyi was describing in The Great Transformation (1944), looks like.2

Why does this matter? Because the thrust of modernity is to rationalize, formalize, separate, dissect and dissemble. Starting in the 1600s, targeting these complex partly unlicensed para-liturgical and communitarian engagements, the Protestant reformers sought clarity about what was, and what was not appropriate to the domain of ‘religion’ or the precise ritual of the liturgy. In hindsight, this was an early expression of what Seligman refers to as the shift from polyvalent, open-ended and constantly negotiable ritual imaginary to the more binary, objective, resolvable and either/or sincere modality. For a short exposition of Seligman’s contrast between ritual and sincerity, see my post here.

Seligman’s narrative also fits comfortably, with Iain McGilchrist’s (substack) description of a lurch towards left-brained modes of attention.

But this pattern of dissembling and functional separation with a few to control has become so overwhelming that we are barely aware of it. Clearly is at the heart of the scientific method. Frances Bacon made no bones about it in his Novum Organum (1622) manifesto.

The human understanding is of its own nature prone to abstractions and gives a substance and reality to things which are fleeting. But to resolve nature into abstractions is less to our purpose than to dissect her into parts; as did the school of Democritus, which went further into nature than the rest

It’s a famous quote, quite rightly, because it sort of captures the modernist credo at a very early stage. Just 100 years after Henry VIII’s split with Rome, Bacon exemplified the new spirit of codification and categorical parsing — in relation to the natural world, but also social life and the regulatory spirit necessary for an ambitious nation-state in formation. There is the clear glimmer of the kind for formal, ends-oriented, bureaucratic rationality that Weber connected with the protestant ethic.

With ‘the Great Transformation’, this logic was no longer limited to science or theology. In the emerging ‘economy’, human beings were mobile, detached and (at least notionally) sovereign. Responding to tax vagaries of supply and demand as employees, investors, employers, wage labourers — modern man and woman was henceforth construed as an economic individual (Homo economics obvs.). Increasingly the same logic applied in the sphere of politics — the individual citizen, voting, choosing and acting in the world on the basis of a newly minted theory of natural rights. Thus in both economy — the business of making a living, managing a household and a family — and in the polity, and in protestant religion, following the atomizing logic of science, the corporative, unitive world of natural law associations of family, parish and neighbourhood are unwoven. The result was construed in terms of an extremely bogus projection of atomic man in a natural state — the Robinson Cruso-esque (sometimes more/less) ‘noble savage’ that animated the imaginations (and nightmares) of Hobbes Locke, Rousseau, Voltaire, Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant.

Modern life is rubbish: who knew?

The logic of pathological individualization, the erosion of communitarian forms of corporative association, and the undermining of particular places with their own histories, memories and traditions — now dominates every aspect of modern culture.

Famously, in her 1961 classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs referred to modern city planning in terms of ‘Euclidean zoning’ involving subdivision regulations restrain that density, disaggregate primary uses, separate activities by function and prioritize traffic needs in road-way designs and eschew the preservation of older buildings (with all the implies in terms of shared memories and the mythos of place). This functional segregation and geographical spreading of all the constituent human activities that constitute a society, over vast sprawling urban systems, signalled the death of a unitary culture. Very briefly, the interweaving separations that now define modern life include:

City from countryside: urban life is now completely severed from the metabolic sway of food producing rural landscapes

Work from home and production from consumption: initially the segregation of manual paid work in large factories disorganized the home as ‘oikonomia’ — which is to say household management, stewardship, processing, production, repair and allocation. Instead, the modern home has become a locus for mass consumption.

Men from women I: initially this separation of work from home, saw women reduced in status, to a category of ‘housewives’, caricatured in turn by the mid 20th century cultural commentary as being prepared by nature to express the capitalist potential of a ‘2 up and 2 down’ suburban estate, or alternatively, passive, depressed, unfulfilled, controlled — tied to unachievable but heavily advertised standards of beauty, vicarious wealth and parental achievement, and sustained by a diet of valium and gin.

Men from women II: as women entered the workforce, and took advantage of the illusory liberties of the sexual revolution (see

or the detailed references in this post), men were further separated from women by the erosion of the natural and socially-validated complementarity of the sexes. In a world of contraception, abortion, fault-free divorce, the welfare-state-father, myriad interventionist state agencies and eventually hook-up culture, the multiple, imbricated and complex purposes that men and women provided for each other, under conditions of Natural Law and refined by Christian marriage — began to evaporate and dissolve.Children from parents: state schooling completed the destruction of the homestead as a fractal miniature of society. At once, children were taken from any productive involvement in the family ‘oikonomia’. Relationships of mentoring and skill acquisition involving parents, but also extended family members and neighbours, gave way to formal, rationalized, impersonal accreditation. Formal education is purpose designed to break down familial and place-based attachments. That’s a big part of what it is for. Nation states need abstract individual citizens. They absolutely do not want tightly bonded families and mutually identifying place-based communities. The first purpose of state education systems was to break down clan society.

Nuclear from extended families: promoting social and spatial mobility by design, and creating all manner of state and market backstops (e.g. public or private childcare), modernity is from the start corrosive of extended family (for more on the this see Mark S. Weiner’s book on the necessary precursive liberal destruction of clan society; or Ernest Gellner’s classic Nations and Nationalism)

From the destruction of families to the collapse in fertility: Eventually, not even nuclear families can sustain the pressure. Changing social attitudes, access to the labour market, and a suite of reproductive technologies and state welfare systems have allowed many women to imagine that they can cope without any men at all. But beyond this — with access to drugs and porn 24/7, a growing segment of young men are giving up on family life as a goal and even physical sex; whilst at the same time, women are stopping having children. The result is a now well documented fertility crisis and demographic implosion across the modern world, from China and South Korea to Russia, Germany the UK and Scandinavia.

People from creative work: as Karl Marx, William Morris but also numerous guild socialists and catholic distributists repeated on a loop, modern capitalist work environments were often dehumanizing. It was not simply, as both Adam Smith and Marx had noted, the simplification and routinization of skilled craft work; but as Lewis Mumford argued, the invasion of machine technics into other areas of life.

How should we sleep….and eat?

One feature of craft work at the level of homestead and community is that it isn’t done necessarily ‘on demand’ or in relation to some pre-defined bureaucratic schedule, but fades in and out of a wider implicate order depending on the weather, seasonal cycles, myriad activities taking place in the same milieu, individual inclination and artistic inspiration, functional imperatives or the time-frames of other households or institutions. This is doubly true because any holistic craft or artisanal activity — whether something artistic, or simply managing a small flock of sheep, carpentry, operating a machine shop, processing meat, or mending your own vehicles, house repair, cheese making or brewing — actually usually involves dozens of subsidiary activities involving varying levels of skill, and which must be juggled in train with each other. In other words, there is a continual process of adjustment and engagement not just with materials, or some creative process of design and manufacture, but with a range of other people and activities, pertaining to the full gamut of human experience — and across domains that defy univocal categorization as this OR that.

There is a pattern in all of this. At the beginning I alluded to a kind of powerful simplification that lends it self to abstract maps, scientific modelling, protestant expressions of sincere piety and univocal explanation and the cold calculus of price-setting markets (where prices are a pure function of supply and demand rather than attending to broader contextual, social factors such as local tradition or political whims). It is powerful because it can concentrate both mind and resources — being associated with that left-brain facility for grasping, honing and analysis, described by McGilchrist. But by the same token, this mode of attention and organization prioritizes simple (or complicated) rather than than complex solutions and arrangements which eschew constant calibration ‘on the fly’.

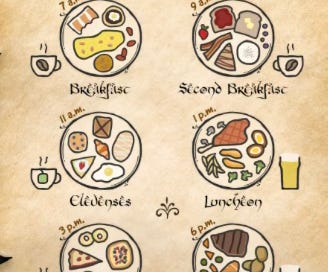

The hobbits’ quizzing Aragorn on the imperative of second breakfast provides a humorous synecdoche for the hierarchy of hobbit values — in which social making and eating of meals lands somewhere near the top. But the term speaks to a pre-modern reality of a much broader suite of meal-terms that spoke to more complex and flexible homestead work patterns involving different combinations of people at different times of the year and in relation to different patterns of cooperative work (harvest, cider making, slaughter, hunting, weaving, wool preparation etc.). This culture and its lexicon survives in East and Central Europe with zweites Frühstück (Germany) drugie śniadanie (Poland) desiata (Slovakia) tízórai (Hungary) and Jause (Austria) referring to a small meal between breakfast and lunch, sometimes involving special food and recipes eat only on this occasion.

The rationalization of the working day during early-modernization saw peasant polyvalency transformed into the endlessly repeated ‘breakfast dinner tea’ of Northern England (dinner at lunch time, for the working man). The complexity and nuance of timing, quantity, recipe and company that was a feature of homesteading life gave way to mechanical repetition and predictability in the social arrangement of meal times.

However, this was only phase I. As the food system was industrialized, from farm to plate — food became fast, disposable and increasingly antisocial. Neither the complex array of pre-modern conventions and collaborations, nor the mechanical predictability of the factory canteen, food culture has been disorganized and individualized on a scale that would be baffling to our ancestors, and perhaps indecipherable to previous generations of anthropologists who made so much from the revealing distinctions operative in all human food cultures (Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger; Levi Strauss’ The Cooked and the Raw). Fast food grazing and the ubiquity and variety of calories and protein, has turned the business of eating into something approaching pure metabolism, devoid of comprehensible, legible and shared conventions and norms.

Which brings me back to sleep. Modern people can’t sleep, won’t sleep, don’t sleep - at least not very well. Sleep apnea and other disorders —with their predictable CPAP machines and holistic potions — are as common in North America, as gluten intolerance. The reasons are many. Some of us are too fat (that’s me), drink too much (me again), spend too much time on electronic devices (me — right now), stay up too late (me) and don’t get enough exercise. We are mentally stressed out, and in a constant ambivalent state between flight and fight. This is partly because of the very internalization of constraints upon violence which have made modern societies so less violent at the granular scale. In his 1939 magnum opus On the Process of Civilization, Norbert Elias showed in great detail how this state of ambivalence is written into the patterns of interdependency and social opacity that define more complex societies. It’s much harder to be sure how people will react.

However, it is also because we have relinquished the kind of complex, flexible, responsive enfolding of human circadian, social, parental, seasonal, and ever changing, task-driven rhythms of homesteading, home-made and home-regulated life. In warmer climates, the traditional siesta — from the Latin phrase sexta hora, ("sixth hour" or noon) — has declined under the pressure of modern rationalization, despite the fact that for the chattering classes it is well known that ‘modern science shows napping is healthy’ But for just a minute, take seriously the possibility of a life in which the work of subsistence partially overlaps with home life, which is the site also of some aspect of extended familial care and the platform for child and teen socialization and learning. It is easy to understand, in such a context, how more flexible and responsive, and tailored patterns of sleep might re-emerge. Homeschooling/home-working parents will probably recognize the constantly shifting dance of sleeping and wakeful babies, mothers and fathers, older parents who retire at 7.00pm to wake with the sun-up. The intuitive healthiness of this kind of pattern is precisely because it is not prescribed — like a school timetable — for ever and from without. Rather it is ‘autopoietic’ in generating itself in response to everything else going on around — and will adjust automatically. If autopoietic complexity is an index of good health — in the body, in ecological systems, in local economies — then probably also in patterns of eating and sleeping. By the same token, a culture which takes greater joy in the lexical and practical diversity and contextual specificity of a ‘way of life’ is probably going to be more resilient and in ruder health — and we all need a bit more of that.

References

Marc Bloch (1961) La Societe feodale, 2 vols. Paris, 1939-40. English trans., Feudal Society, 2 vols. London, 1961.

Ginzburg, Carlo (2013). The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hutton, Patrick (October 1981). "The History of Mentalities: The New Map of Cultural History". History and Theory. 20 (3): 239. doi:10.2307/2504556. JSTOR 2504556.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation. Farrar & Rinehart, inc.

Polanyi, K. (1957). Trade and market in the early empires; economies in history and theory. Free Press.

Polanyi, K. (1968). Primitive, archaic, and modern economies; essays of Karl Polanyi. Anchor Books.

See Marc Bloch 1961; Carlo Ginzburg 2013; Patrick Hutton 1981.

And it was to explore the dynamics of a more embedded pre-modern economy that we left behind, that Polanyi went back to anthropologists such as Colin Firth and Bronislaw Malinowski (see Polanyi 1968 and 1957)