Looping the Tristan Chord: Civilization is subject to hard cognitive constraints

Musk's Mars Mission will Founder on our Stone Age Brain. The failed Interweb reveals that the cognitive limits of human expansion are not technical but social and psychological.

Musk wants us to go to Mars. It shows very human ambition. Human mythology is full of it. The tower builders of Babel, Prometheus, Daedalus & Icarus, and Faust — all exerted themselves against human limitations. Usually it doesn’t go so well. Perhaps the conservative impulse against ignoring traditional wisdom has something to it. The Internet and social media are the but the latest arena for hubristic implosion.

Are people really this crazy?

I have given up Twitter a few times. Mostly because of the backlash against conservatives in universities. My job has been, and still is, on the line. If it was just me — a pugnacious, chippy little sod from North East England — I would probably say ‘Bring it on!’. But my wife’s health has suffered. And the dynamics of public cancellation, shunning, shaming and potential redundancy has an obvious impact on my family — on their careers, social networks and financial security. So, without much good grace it has to be said, I have usually stepped back. But here I am again, albeit under a nom de guerre, ‘speaking my truth’, engaging with the world and trying to to advance my new found faith and small ‘C’ conservative politics.

Occasionally I have been rancorous and ungenerous online, meeting juvenile insult with the same. Mostly, I try to be more grown-up — only because I made a promise to my wife. She’s right about this though — as in most things. Anyway, as Substack becomes more like Twitter, the horrible spirit of bitter zero-sum verbal contestation has come with it. The antisemitism is the worst. People calling shamelessly and without compunction for the death of all Jews and the destruction of the state of Israel. This little haul is from this morning — from people who object to being called out.

The most egregious hater was one Dan Gilfry who seems to be an ex-soldier and mercenary — and very far gone in the bile department. He blocked me but you can see from his biog. that he is overflowing with the milk of human kindness. He likes kids and animals but hates Jews ‘and their Christian slaves that start wars and destroy the planet with Nazism.’ He takes ‘merc[enary] assignments for fun’ (presumably killing people?). Clearly bonkers. A sociopath perhaps. But he’s not alone. If anything he’s kind of representative of the technology and the sort of people it creates.

As a Catholic, I’m called not to respond in kind but with love — which is to say, willing their good. It was so much more satisfying when I was an agnostic and then a militant pagan. I could dive straight in with an exchange of ‘fuck you’s’ …or as in Monty Python: "I unclog my nose in your direction, sons of a window-dresser!" and "No chance, English bed-wetting types!" Now, things are different. I said I would pray for them to experience calm, equanimity and even joy — and then, true to my word — I sat down and prayed. It kind of irritated even me…but I really did.

I suppose as a Nietzschean hero, Dan Gilfry is at least not weighed down with Freudian repression. Dan is all ‘Id’; there seems to be not one shred of a constraining superego at work here.

The process of civilization

Dan would have had nothing but contempt for Norbert Elias — a Jewish sociologist who escaped in 1938 and whose parents died in Auschwitz. In On the Process of Civilization, Elias showed how civilization is a function of the psychic internalization of external constraints on behaviour in the context of created social complexity. European civilization emerged in the interaction between the extension of markets, more complex civil society and nation-state formation. Social complexity created greater interdependence, which in turn created a kind of endemic ambivalence. The reason for this was that individuals were less able immediately to ‘read’ the opaque structure of social relations. Less able to predict the consequences of their actions, the incentive structures began to discourage impulsive, violent dynamics of ‘reaction’ and instead reward impulse-control and more considered processes of ‘response’. The resulting virtuous cycle saw increasing market confidence, social trust, efficient functioning of increasingly impersonal legal institutions, greater political legitimacy and so on. Western civilization is linked he showed, internally and intrinsically to a pattern of restrained ego-control that is built into the dynamics of socialization and public governance as well as the structure of the average personality.

In the 8th century, the nature of war favoured the Berzerker tactic of mad, raging, loosely directed and uncontrolled violence. In the 21st century, such a personality type would be disastrous on the battlefield. The modern soldier operating a drone or flying a fighter jet is much more likely to embody a psychic habitus of calm, detached restraint. For Elias, the decisive moment in the process of modernization came during the early modern period, with a paradigmatic shift from pervasive and high levels of ‘affective involvement’ to mode ‘detached’ processes of model-making, apprehension and evaluation. Such detachment unfolded first in science but gradually, to varying degrees, in all areas of social and economic life.

One result is that— despite the persistent claims of the Jeremiahs — modern societies are by far the least violent in history (for now). Drawing on Elias, Pinker’s account is less original but the message is the same and he brings receipts. Either way the big picture is very clear. Across the West and in those societies that have crossed over and generated effective trajectories of modernization, levels of interpersonal violence have declined consistently decade on decade, century on century. This aspect of modernity is such that we can feel genuinely squeamish horror reading about cruelty and torture that the Romans just took for granted — and not just the Romans, but all tribal societies. This is the sociological reading of the Tom Holland schtick. Just read any of the accounts of what the Germanic pagan ancestors got up to during the course of a normal day’s pillaging;1 or read Joseph Boyden’s interior evocation of what it was to be an indigenous warrior in the Orenda.

Elias was averse to any kind of Whiggish Victorian progress theory. Certainly, there is nothing in his account that precludes the modern, restrained personality type becoming generalized across the world. But he was also very much aware of the downside of the restrained modern habitus. Neither did he discount phases of reversal and ‘decivilization’ and wrote an extended analysis of Germany and the Germans, to account for the descent of the Nazis into the maelstrom of inhumanity. But nevertheless, he was perhaps mildly optimistic and saw no reason why, in principle, the internalization of psychological restraints could not keep up with human technological prowess.

Civilization makes people rich but unhappy and mentally unstable

However, mythology and early 21st century sociology suggest otherwise. Icarus was not let down by his tech. The wings worked just fine. It was his desire to fly ever higher. A failure of impulse control saw him burn and crash down to Earth. It seems that on many fronts, we are having our Icarus moment. Although the process of civilization is a theory of the expanding average capacity for impulse control, there is no reason to expect that it should be unlimited or that there will not be tipping points. There must after all come a point where the superego function described by Elias becomes so great that the constrained human subject becomes a qualitatively different entity. Perhaps it is at this point that C.S. Lewis’ ‘abolition of man’ kicks in. But just as likely, it may be impossible to reach this point. Ecological conscience formation — the creation of the superego — is a function of ‘ontogeny’ or the growth and development of individuals. It is not a phylogenetic aspect of ‘species’. Formation and socialization taken place within a single life-time, and mostly within a single childhood. Created in the image of God, our human nature bequeathes a potential for good conscience — and even for us to become Saints. But the Saints remained human. They did not evolve the hard-wired, implacable impulse control of an automaton. Even our Lord was subject to temptation in the desert. To be human is to be tempted. To be saintly is to resist temptation. To be temptable entails hard upper limits to impulse control.

But the Saints remained human. They did not evolve the hard-wired, implacable impulse control of an automaton. Even our Lord was subject to temptation in the desert. To be human is to be tempted. To be saintly is to resist temptation. To be temptable entails hard upper limits to impulse control.

Pre-modern people were more impulsive, less introspective, more volatile, more prone to sudden bouts of gaiety, capable of quite unconstrained cruelty, and equally liable to transition into extreme, no-holds-barred violence. They were much less prone to depression and psychological malaise. This natural pre-civilization sensibility tended towards the psychological polarities: fight or flight; happy or sad; relaxed or tense and vigilant. Moderns by contrast are caught in a perpetual state of ambivalence. Urban living has acclimatized people to living in close proximity to an enormous and never-ending flow of strangers. For hunter-gathers, strangers were a rare thing— an opportunity for trade and hooking up, or for conflict and violence. To be live permanently with strangers is to experience never-ending ambivalence; continual unresolved stress. This is why modern people tend towards anxiety, depression and unhappiness. Life has come to be defined by the experience of ‘un-resolution.’ In musical terms, we are stuck in something akin to the Tristan chord in the opening to Wagner's 'Tristan und Isolde’ — a dissonant chord (F, B, D#, and G#) creating a sense of unresolved tension and longing. Listen to it here. Does that not scream modernity, shopping malls, Internet chat rooms and ChatGPT? It’s Munch’s The Scream rather than Constable’s The Hay Wain.

For starters, all the psychic internalization that creates that strong regulatory superego, develops according to Elias through a quasi-Freudian process of repression and sublimation. One consequence is that, although Pinker is right that modern society is much less violent, it is also much less happy. Compared with their tribal ancestors, modern people seem to be really screwed up. Every account of modernity picks up some aspect of this. Here is a list:

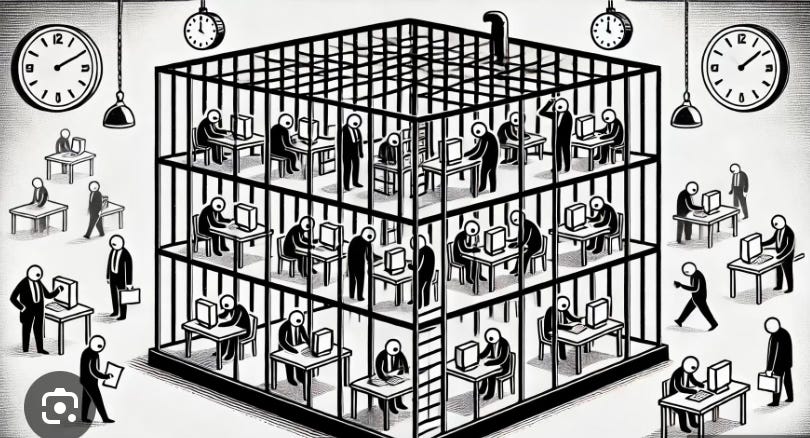

For Max Weber modernity leaves people individualized, disenchanted and trapped in a bureaucratic iron cage which erodes ontological meaning, leaves people hopeless and subjugates a substantive orientation to shared, meaningful societal ends in favour of formal, instrumental rationality geared to means.

For Marx, the wage relation and the labour process left workers trapped in a permanent state of alienation – separation from the fruits of their labour, from their fellow beings and unable to express their species being in conscious, collaborative social production of useful objects necessary for subsistence and pleasure.

For Durkheim, the massive extension of the division of labour and the fragmentation of communities and families leaves the individual exposed without any intermediary associations or networks shield them from the overpowering scrutiny and direction by the state.

For Tonnies and Polanyi, modernity involves the disembedding of individuals and families from the cosy, place-bound rural ‘Gemeinschaftlich’ communities of traditional society. The lattice of mutual obligations and patterns of reciprocation are replaced by heartless bureaucratic allocations and market transactions which consistently undermine the personhood of individuals.

In the 20th century this pattern of critique continued with modernity being characterised in terms of: narcissism (Lasch, 1991); an empty therapeutic culture (Rieff, 1973); empty, meaningless individualism (Trueman, 2020); disenchantment and the severing of the sacred order from the social order (Rieff, 2006); a crisis of individual mobility and loss of trust (Bauman, 2000, 2003; Putnam, 2000, 2007); a catastrophic implosion of marriage and sexual complementarity (Carlson, 2015; Perry, 2022; Regnerus, 2020; Tucker, 2014) etc.

I’ve covered this story in other essays - like here:

The bottom line is that all the stuff, all the health, all the technological advances and all the freedom have not made people happy.

The bottom line is that all the stuff, all the health, all the technological advances and all the freedom have not made people happy.

Modernity was the first society in which the questions ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What can I be?’ were even comprehensible. Hitherto, even the richest and most powerful members of society inhabited and lived out patterns of behaviour that were substantially ascribed by the place in the social order in which they found themselves. If this was true even for Kings and Queens, how much more so for peasants. Tony Robinson’s character of Baldrick in Blackadder perfectly captured the timeless certainty of outlook, expectation and room for manoeuvre (zero!) that this pre-modern ascriptive society entailed.

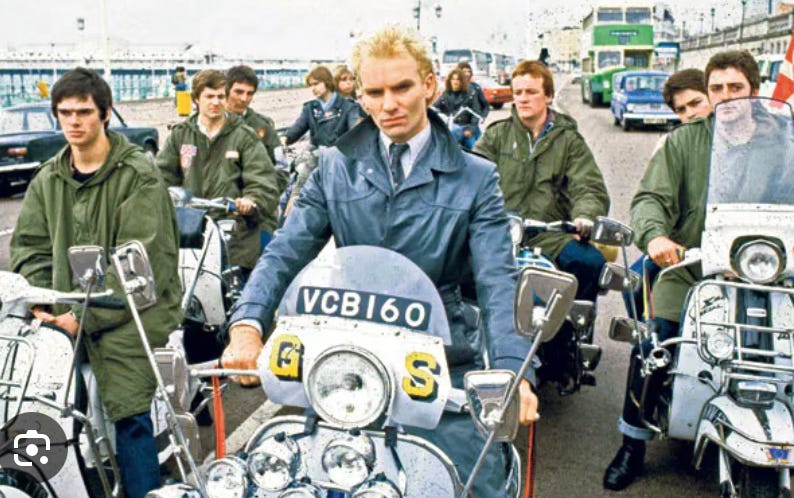

Suddenly, to be able to invent a character and choose a life became the defining myth of modern consumer societies. The UK was never as naively Pollyanna-ish as the Americans with their peculiar ‘dream’. And jumping on scooter and heading to Brighton never had the glamour and potential of the westbound Route 66.

But since the 1960s, popular culture has become youth culture. The kids rule. Buoyed up by endless cycles of consumer fads and fashions — manipulated by market moguls and authentically self-generated in equal measure — youth culture has stuck to a single, overarching truth: ‘you do you’. And the age of the kids who are ‘doing themselves’ has increased with every decade. In the beginning, youth culture pertained to teenagers on the cusp of entering employment and becoming adults. Blue suede shoes quickly gave way to corporate brogues. They got married and had kids in their early 20s. By the 1970s, youth culture was played out by kids in their late 20s and 30s, and they were getting married and having kids later to boot. By the ‘80s and ‘90s, the game was up. The kids were often not getting married, not having kids, and, in effect, refusing to enter adult society at all. This was sometimes dressed up in the radical language of socialist feminism. But mainly it was a function of diffuse, undirected egotism (I’m speaking about myself btw). Kids don’t want to take responsibility. Society had stopped demanding it of them. And suddenly society was full of youths in their 40s and 50s, dominated by the (wo)man-child.

At the same time, the implosion of inter-generational culture — not just as a result of mobility, the increasing gap between grandparents and grandchildren, but also the collapse in family size, one-parent families, single-child families and the disappearance of siblings — all resulted in what Gabor Mate identifies as the pathological dominance of horizontal peer-group relationships. The kids have started bringing themselves up, and socializing each other. The Internet is peer-group socialization by (wo)man children on steroids.

The kids have started bringing themselves up, and socializing each other. The Internet is peer-group socialization by (wo)man children on steroids.

So, what happened? How did it play out? Did all the vigorous and sometimes demented expressions and acting out of every conceivable thought and desire — the elimination of all constraints on personal behaviour — did this make the kids happy? That of course is a rhetorical question. We all know the answer. The kids are unhappy, mentally ill and more prone to suicide. Autism, gender-dysphoria, anorexia, bulimia, depression, obesity, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), nature deficit syndrome - all this crazy BS has all become part of the language of parenting. Everyone is on ante-depressants and in therapy. Nobody is having kids. Johnathan Haidt is surely correct to point the finger at technology and specifically social media and smart phones (Haidt, 2022; Lukianoff & Haidt, 2015). But actually, when society simply stops reproducing itself, it’s a pretty good indication that something is wrong.

In his famous account of the Ik — The Mountain People — Colin Turnbull argued that being forced into a kind of radical individualism in order to survive, this tribal people began to eschew care for dependents, to refuse any responsibility for others, to avoid sharing, reciprocating or cooperating — and treating old and sick people and even their own children purely as burdens. Losing the traditional hunter-gatherer way of life and the age-old pattern of marriage, childbirth, death rituals/taboos, and religion, the Ik he argued had imploded as a functional society and was unable to sustain or reproduce itself.

Turnbull’s account was controversial and critiqued — obviously, it’s anthropology. However, his description of societal dysfunction seems not a million miles from what we are now experiencing across the Western and wider modern world. Pervasive anomie associated with a meaning crisis, radical individualism, unhappiness and crashing fertility.

Which brings me back to Musk and all that venom and bile on social media. Elias’s account of the civilizing process centres on two things. Increasing social complexity — as a function of market economies and a radical expansion in the division of labour — makes opaque relationships with strangers, in a situation of uncertainty, the default experience. At the same time, the developing capacity of central state vis-a-vis local warlord facilitates the development of a series of monopolies — the most important of which pertains to the exercise of legal violence. It is the predictability and consistency of this monopoly on violence — combined with an increasingly elaborate legal system with bureaucratic institutions for policing, enforcement and incarceration — which facilitates what Elias calls the ‘internalization of external constraints.’ Behaviour which is first constrained by efficient external constraints becomes increasingly policed ‘from within’ as it were, as a function of conscience formation or what Freud refers to as a more elaborate Super-ego.

We were not built for cities of strangers.

This more differentiated and elaborate interior life accounts in large part for humanity’s capacity to make the transition from hunter gatherer hearth cultures to mega-cities of millions of people. But it also makes modern people much more vulnerable to psychological malaise and dysfunction. We were not built for cities of strangers.

When external and internal controls become decoupled

The significant thing to note is this bootstrapping interplay between external and internal controls, between the capacities of the state to enforce along with pervasive market incentives on the one hand, and conscience formation on the other. In countries like England, the process of psychic internalization was so effective that the external controls could disappear from view almost completely. British police famously don’t carry weapons. The British army almost never marches on public streets. British people are famous for queuing. All that stuff. Yes they’re also famous for working class football hooliganism (although not so much any more). But never-the-less, the United Kingdom has been a highly pacified society. Centuries of state formation, coercion and disorganization of tribal sub-cultures left the society of individuals able to function more or less autonomously. Elias never said it, but because he takes for granted national society as the frame of reference, he doesn’t consider explicitly whether the governing superego can persist indefinitely without the background structure of external constraint.

The Nazi holocaust had shown the peculiar modern form of ‘decivilization’ that could arise when a totalitarian state, in conjunction with concerted social pressure, overrode the interior constraints of conscience. The industrial death camps combined the capacities of an elaborate bureaucratic state in a highly militarized context of pervasive external controls, with a very selective pressured relaxation of particular psychological controls for those involved in the killing: brutal and pathological but far removed from a viking berserker or the death-lust of Iroquois warrior. Nazism was unique because it forged a kind of bureaucratic, formally-rational tribalism in which otherwise modern (ambivalent, repressed, restrained, moderately happy) individuals were able selectively to disengage restrains on violence in very particular contexts. This was what Hannah Arendt captured when talking of Eichmann she referred to ‘the banality of evil’. In 1971 she wrote:

I was struck by the manifest shallowness in the doer [ie Eichmann] which made it impossible to trace the uncontestable evil of his deeds to any deeper level of roots or motives. The deeds were monstrous, but the doer – at least the very effective one now on trial – was quite ordinary, commonplace, and neither demonic nor monstrous.

So much for over-determination of the psychic habitus. The Internet is now engendering the inverse problem: the process of socialization and conscience formation is operating in a global arena without any comparable global structure of external constraints. There can be no global police force, or military; no global government; no global architecture of legislation, courts, judicial process and incarceration. And because the structure of external constraints remains resolutely national — with hyper-individualization, the breakdown of the ascriptive qualities of family and community, the uber-mobile billiard-ball individuals who increasingly live out their lives online, are becoming relatively unconstrained by either social pressure or state sanction. In this context, the Superego structure that made pacified modern living is unravelling. What Jonathan Haidt (

) describes as a problem of teenage mental health is actually turning into a dynamic of wholesale decivilization.In the free-for-all of the Interweb, millions of individuals are showing signs of seriously pathological conscience formation. Whether it’s porn and sexual violence (OnlyFans, Porn Hub, Andrew Tate), the grotesque demonization of political opponents, the rampant rhizomic growth of perverse gender pathologies, or the unhinged hatred of Jews and Israel — the online environment is making people ill and disorganizing their capacity to live together.

The mismatch between the maximum effective scale of external regulation — the national society — and the new de-spatialized, disembedded patterns of socialization and infinitely micro-patterns of identification, is also beginning to de-pacify national societies. Even after the wave of globalization in the 1980s, right up until the emergence of the Internet, the national societies wrought during the process of modernization mostly worked. With a rough balance between the scale and intensity of external controls (laws, policing, social norms rooted in language cultures, market incentive structures) and internal controls (conscience formation, a distinctive societally-inflected superego), liberal/social democratic nation states experienced low levels of interpersonal violence and relatively high levels of social trust.

Certainly there were problems with the trajectory. Unhappiness and depression were increasing. The demographic and social fallout from the sexual revolution was beginning to make itself felt. Women in particular were beginning to experience the spiritual and social boomerang of their hard won sexual, ‘unmarital’ and occupational freedoms — which manifested in the ‘paradox of declining female happiness.’ But this was all slow burn, frogs in pans stuff. Life went on.

What has really accelerated the crisis is the Internet. If Nazism was a function of ferocious external controls becoming excessively superordinate to tight but distorted, warped and manipulated internal controls; the global information society has produced the opposite. For a large and growing minority of Gen Z and beyond, the moulding incentive structures of national society are now virtually non-existent. Without strong families, complementarily-sexed parental role models, strong fathers and community father figures; without place-bound and community-oriented matriarchies and ‘Aunt-networks’; and with an increasingly if selectively permissive state — young people are ‘formed’ online. The process of socialization — the pattern of conscience formation — has become idiosyncratic, narcissistic and voluntaristic. Teenage jihadists, Jew-hating Islamophile Queers, transgender identitarians, young girls who identify as ‘hobby horsers,’ furries (of course), all the ‘normal’ fetish-wallahs who come out on Pride marches, ‘minor attracted persons’ (MAPs — AKA societally sanctioned paedophiles), cognitively dissonant eco-warriors (Xtinction Rebellion) — these are all part of the same phenomenon i.e. the deformation of the superego and the chaotic release of the Freudian Id.

This mismatch between the maximum structure of external controls in national societies and the disembedded, de-spatialized, unanchored context for conscience formation can be seen as the outer cognitive limit of civilization. Conceivably, we could imagine upscaling external controls — markets, laws, policing, incarceration, ascriptive patterns of culture — to the level of a global society. But to get as far as the nation-state required centuries of coercion, violence and the active, often brutal, suppression of tribal language cultures and patterns of identification. This carried on in Europe right into the 20th century — and cases such as the Basque Country straddling France and Spain, is ongoing. The manifest failure of the EU — an attempt to forge a European national entity by coercive bureaucratic consensus on the back of monetary union — if nothing else shows just how impossible this task is. As the world falls back into the Westphalian pattern of nation-states, geo-political realism, strategic alliances and bilateral patterns of cooperation, we would do well to reflect on the underlying psycho-affective constraints to cooperation at larger scales.

As is pointed out on Substack a dozen times a day, human beings are equipped with a Stone Age brain. Our cognitive priors make our achievements in science and technology, but most of all in terms of cooperation beyond basic tribal and familial groups, astonishing. But by the same token, it seems likely that this plasticity is not infinite. The creation of national societies and the reduction of interpersonal violence have clearly been positive in terms of normalizing and institutionalizing more caring and benign forms of cooperative living. But they have already come at great psychological cost. Even were a cohesive global society possible, it would seem to imply a level of psychological repression and Superego formation that is probably intolerable. In a previous post, I mentioned James Lovelock’s comment that an ecological civilization on a global scale (Gaia) might be possible only if human beings internalized such individual restraint as to become like worker bees in a hive.

Can our humanity survive the circular economy?: On edible insects, lab-grown meat and 'going green'

Even if we could, I don’t think most of us would choose such a scenario (perhaps those hardcore ecocentrics in Xtinction Rebellion). But actually we can’t and the attempt to engineer such an outcome will lead — is leading — to disaster. If the Tristan chord represents the inner life tension of modern life, then any attempt to create something bigger will probably sound more like Donald Sutherland’s Scream in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Some references

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Polity.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Liquid love : on the frailty of human bonds. Polity Press.

Carlson, A. C. (2015). The Natural Family Where It Belongs. Transaction Publishers.

Haidt, J. (2022). Johnathan Haidt Debates Robby Soave on Social Media.

Lasch, Christopher. (1991). The Culture of Narcissism. Norton.

Lukianoff, G., & Haidt, J. (2015). The coddling of the American Mind. In Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/399356/

Perry, L. (2022). The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A new guide to the 21st century. Polity.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American democracy. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and the …. http://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?hl=en&q=putnam+bowling+alone&btnG=Search&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=&as_vis=0#3

Putnam, R. D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), 137–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x

Regnerus, M. (2020). Cheap sex : the transformation of men, marriage, and monogamy. Oxford University Press.

Rieff, P. (1973). The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud. Penguin.

Rieff, P. (2006). My Life Among the Deathworks. Sacred Order/Social Order Vol 1. University of Virginia Press.

Trueman, C. (2020). The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism and the Road to the Sexual Revolution. Crossway Books.

Tucker, W. (2014). Marriage and civilization : how monogamy made us human. Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Consider this account from the Muslim traveller Ibn Fadlan of the funeral of a Viking chief in what is now Russia in 921AD. The send off included a ritual mass rape of a slave girl who is then strangled, stabbed multiple times and then burned on the pyre. https://www.mrtredinnick.com/uploads/7/2/1/5/7215292/ibn_fadlan_-_account_of_a_viking_burial.pdf